Sophia, the world’s first robot-citizen, attends the Word Investment Forum on October22, 2018. UN Photo/Jean Marc Ferré.

By Mariana Meneses & James Myers

In 2017, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to Sophia, the world’s first citizen robot. As rapid advances in science continue, what will the future hold for relations between humans and their technological counterparts? Can our laws, many conceived in the pre-digital era, be adjusted to maintain reasonable and responsible control over artificial intelligence?

Many questions quickly arise as we face these glimpses of our future. What will full citizenship entail for a robot, in terms of rights and duties? In democratic countries, will they be allowed to vote in national elections? In fact, how will these machines fit into the political process? How will politicians respond to the developing technology when some seem to know little about it, and at what point will there be a conflict of perception?

Although some of these questions may remain a mystery for the near future, it seems we might be starting to make some advances in AI regulations at a global scale.

Sophia is Hanson Robotics’ most advanced human-like robot.

One of “her” most impressive features from the beginning was an ability to imitate dozens of human facial expressions. But one acquired trait has made her even more famous: her passport, as, since 2017, she has been a full citizen of Saudi Arabia. And there is more to her story.

Besides being the first non-human to carry a credit card, she also became the first robot Innovation Ambassador for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in a role related to sustainable development and the safeguarding of human rights. According to the UNDP:

“Experts believe that artificial intelligence such as Sophia marks the coming of the fourth industrial revolution and will bring about a dramatic shift in how technology can help solve some of [global] development’s most intractable problems. In partnership with Sophia we can send a powerful message that innovation and technology can be used for good, to improve lives, protect the planet, and ensure that we leave no one behind.”

However, many are not so optimistic, and some experts have voiced concerns. This was the case with the Open Letter to the European Commission, mostly against the creation of a Legal Status of an electronic “person” for robots that they refer to as “autonomous, unpredictable and self-learning.” The signatories argue that such status would be “ideological and non-sensical and non-pragmatic.”

According to their website, the letter is signed by “Political Leaders, AI/robotics researchers, and industry leaders, Physical and Mental Health specialists, Law and Ethics experts [that] gathered to voice [their] concern about the negative consequences of a legal status approach for robots in the European Union”. Their main concern is for human safety: “The European Union must prompt the development of the AI and Robotics industry insofar as to limit health and safety risks to human beings. The protection of robots’ users and third parties must be at the heart of all EU legal provisions”.

But what kinds of regulations do we have in place today? And who are the main actors in this debate?

This is the focus of a 2022 paper published in the journal AI and Ethics by predoctoral researcher Lewin Schmitt, from the Institut Barcelona D’Etudis Internacionals (IBEI), who is currently working on the project “GLOBE- Global Governance and the European Union: Future Trends and Scenarios.

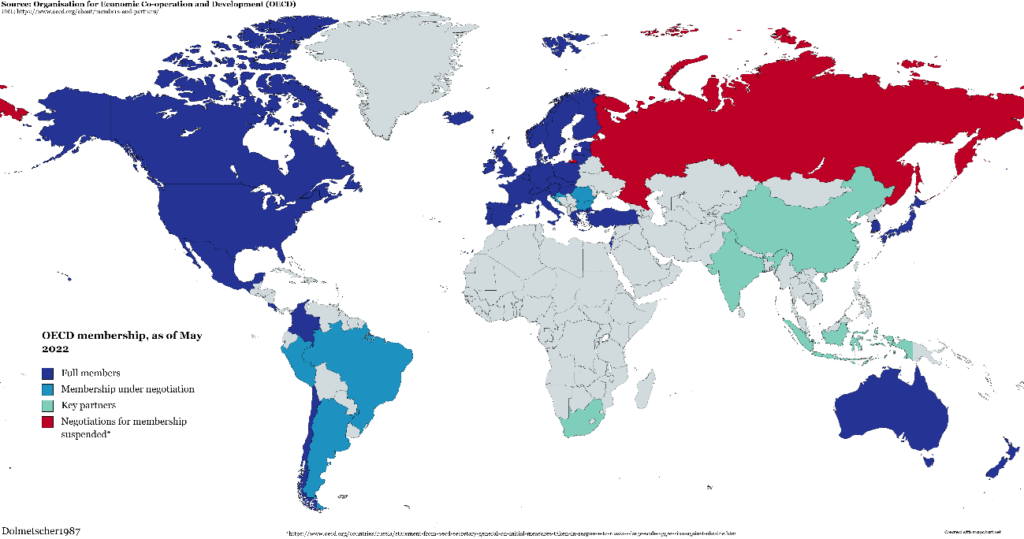

Schmitt shows that “international organizations [have] high levels of agency in addressing AI policy and a tendency to address new challenges within existing frameworks.” He argues that even though the landscape is complex and there are many different actors involved, there is a trend towards a “regime” or system of rules and norms that is centered around the OECD. This means that the OECD is seen as a key player in shaping how AI is governed, and that other actors are looking to the OECD for guidance and leadership.

“The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development is an intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. (…) The majority of OECD members are high-income economies with a very high Human Development Index and are regarded as developed countries. (…) The OECD is an official United Nations observer” (Wikipedia).

OECD member countries, as of May 2022. Credit: Dolmetscher1987.

In general, existing and proposed legislation for regulating AI worldwide share some common elements.

These include requirements for transparency and explainability of AI systems, meaning that an AI should have the capacity to provide clear and understandable explanations of its decision-making processes and outcomes. They also include standards for data protection, bias mitigation, accountability for developers and operators, safety and security, ethical considerations, and data destruction rights. These elements aim to ensure that AI systems are designed and used in a way that is fair, transparent, and accountable, while also protecting the safety and privacy of individuals and promoting ethical considerations.

Here is a status update on some of the current and proposed regulations relating to AI:

The European Union AI Act was first proposed in 2021, and many believe that, if adopted, it could become a global standard. According to the Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonized rules on artificial intelligence,

“The regulation follows a risk-based approach, differentiating between uses of AI that create (i) an unacceptable risk, (ii) a high risk, and (iii) low or minimal risk. The list of prohibited practices in Title II comprises all those AI systems whose use is considered unacceptable as contravening Union values, for instance by violating fundamental rights. The prohibitions cover practices that have a significant potential to manipulate persons through subliminal techniques beyond their consciousness or exploit vulnerabilities of specific vulnerable groups such as children or persons with disabilities in order to materially distort their behavior in a manner that is likely to cause them or another person psychological or physical harm. (…) The proposal also prohibits AI-based social scoring for general purposes done by public authorities.”

The proposal’s prohibition against “social scoring” is a clear reference to the so-called Social Credit System under development in China.

As it is described by Wikipedia (on 3/30/23, after undergoing 49 edits in less than 3 months): “The Social Credit System is a national credit rating and blacklist being developed by the government of the People’s Republic of China. The social credit initiative calls for the establishment of a record system so that businesses, individuals and government institutions can be tracked and evaluated for trustworthiness. There are multiple, different forms of the social credit system being experimented with, while the national regulatory method is based on blacklisting and whitelisting. The program is mainly focused on businesses and is very fragmented, contrary to the popular misconceptions that it is focused on individuals and is a centralized system.”

The Act defines two groups of high-risk AI systems.

The first is composed of AI systems that are designed to be part of products that could potentially pose safety risks to users; these must be evaluated and certified by a third-party organization before being allowed on the market. The second group are “other stand-alone AI systems with mainly fundamental rights implications,” which are listed in an appendix.

It is important to note that The European Union has recently agreed upon using the definition of AI used by the OECD. According to Euractive, the document defines AI as: “Artificial intelligence system (AI system) means a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that can, for explicit or implicit objectives, generate output such as predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing physical or virtual environments”.

Observers, like the Future of Life Institute, caution that the proposed Act “has several loopholes and exceptions” and as a result it cannot ensure that AI will remain as a “force for good in your life.” It also warns that the legislation is “inflexible,” in its inability to address new technologies and applications in the future that have not yet been conceived.

In the United States, the President has issued the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights as an exercise in envisioning a future where the American public is protected from the potential harms, and can fully enjoy the benefits, of automated systems. The Blueprint, which would require some new laws to implement, proposes five guidelines to “help guide the design, use, and deployment of automated systems to protect the rights of the American public in the age of artificial intelligence”: (1) protection from unsafe or ineffective systems, (2) protection from discrimination by algorithms and systems, (3) protection from abusive data practices, (4) awareness when and how an automated system is being used, and (5) guarantees that one should be able to opt-out and find remedies to problems.

In 2022, the Canadian Government proposed a suite of three laws to regulate privacy and the responsible development of AI systems. These laws were designed to strengthen privacy protection and trust in the digital economy, and ensure Canadians retain control over their data, including the right to request its destruction. One of the three laws, the proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, is mainly concerned with Canadians’ trust in the development and deployment of AI systems, and aims, among other things, to:

“[Protect] Canadians by ensuring high-impact AI systems are developed and deployed in a way that identifies, assesses and mitigates the risks of harm and bias; (…) (and) outlining clear criminal prohibitions and penalties regarding the use of data obtained unlawfully for AI development or where the reckless deployment of AI poses serious harm and where there is fraudulent intent to cause substantial economic loss through its deployment”.

In 2019,Singapore adopted the AI Governance Framework, whose guiding principles are that: (1) Decisions made by AI should be explainable, transparent, and fair, and (2) AI systems should be human-centric. The principles define, among other things, clear roles and responsibilities, an appropriate degree of human involvement, and the minimization of bias and risks of harm to individuals.

In Brazil, the 2021 Artificial Intelligence Strategy follows the definition of AI adopted by the OECD. “We need the technology to be human-centered and to be in line with fundamental human rights. [We need it to] fight against discriminatory, illicit or abusive behavior,” said a Brazilian congresswoman in 2021, during the voting and approving of the AI bill by the Congress, which also focuses on encouraging technological advancements in the country. Currently, the bill is under the approval process in the Senate.

In a 2023 paper published in the journal Computer Law & Security Review, Dr. Luca Belli, Law professor at FGV, Brazil, and co-authors argue that the Brazilian proposed framework for regulating AI doesn’t do enough to understand the potential consequences of AI, and as a result the proposed regulations may have little effect. Additionally, the proposed regulations conflict with existing laws meant to protect consumers, ensure transparency in data use, and prevent discrimination. As legislators continue to discuss the matter, there are potentially many changes yet to come.

To sum up, as Dr. Nisha Talagata argues in Forbes, “there are many regulations in development, and to make things even more complicated, they differ in their geographical or industry scope and in their targets. Some target privacy, others risk, others transparency etc. This complexity is to be expected given the sheer range of potential AI uses and their impact”.

The unaccountable, or unchecked, use of AI could bring many perils to any nation. In fact, a 2022 survey covering the opinions of 327 researchers of artificial intelligence found that 36% of AI scientists around the world believe AI decisions could cause a catastrophe on the scale of nuclear war in this century.

The development of AI has always been surrounded by controversy, and as it is increasingly applied for a multitude of purposes, our institutions need fast developing legal frameworks to guide us through this technological revolution.

To Lewin Schmitt, in his 2022 paper on AI and Ethics: “Partially, this work will take place at the national or even sub-national level. However, to a large extent, AI policy will be shaped internationally. Cutting-edge AI research is already a global enterprise dominated by large transnational technology firms. Moreover, the cross-border nature of the digital ecosystem renders purely national regulatory regimes inefficient and costly. Hence, big parts of the discussion around ethical AI and AI governance (…) focus on the international level.”

Street art in New York City, USA. Credit: Jess Hawsor.

Finally, there is also the issue of regulating the use of AI to write laws.

As Nathan Sanders and Bruce Schneier note in this MIT Technology Review, although the potential benefits of AI-generated laws include increased efficiency, reduced bias, and improved responsiveness to emerging issues, the challenges of using AI in lawmaking include perpetuating biases, lacking nuanced understanding of human values and ethics, and lacking legitimacy and accountability. AI can help identify gaps and inefficiencies in existing laws, automate the drafting of routine documents, and generate options and scenarios for policymakers. However, ethical considerations such as accountability, transparency, bias, and alignment with democratic principles and human rights must be addressed for responsible and ethical use of AI in lawmaking.

Although AI technology is already considerably developed, AI regulations are in their early stages and remain relatively absent from the public debate. But we should start to consider how we will view the developing super intelligent robots: as autonomous beings, or as tools – and the consequences either way. How will things look moving into the future, with such fast-moving technology? While the regulations take shape, we’ll have to wait and see.