Illustration by axbenabdellah, on Pixabay.

By James Myers

The buying and selling of data is a huge and profitable business that some consumer protection agencies have been working to regulate. The regulatory progress of at least one such agency is now threatened.

In operation since 2011, the United States Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is facing elimination by the incoming administration if its designated efficiency czar, Elon Musk, has his way. Musk, the wealthiest human in the world, called for the bureau’s deletion in a November 27 post on X (the social media platform that he owns), on the basis that other government agencies provide similar consumer protection.

Musk’s post didn’t indicate which other agencies perform the same work, although his demand is consistent with the new administration’s campaign pledges to reduce financial regulations.

Politico reported that “Musk’s statement comes less than a week after the CFPB finalized a regulation that would expand its oversight of big tech companies that offer payment and digital wallet apps. That would potentially include X, which has explored ways to enter the payments business.”

In the 13 years since it began operation, the CFPB reports that it has obtained $19.6 billion in relief for consumers who were subjected to unfair practices by lenders, and the agency has extracted $5 billion in civil penalties against bad actors.

The CFPB proposes to extend regulations to data brokers.

In our April 2023 editorial, How Data Brokers Profit from the Data We Create, we reported on the data brokering industry that, according to some sources, is estimated to produce $200 billion in annual revenue. The industry is subject to few restrictions and no disclosure requirements, and companies that engage in data brokering don’t widely advertise their activities. It is commonly thought that the activity of data brokers is kept quiet because if consumers knew the extent and value of their transactional data that’s traded there would be demands for greater regulation.

The vast scope of the data brokering industry has indeed drawn the attention of regulators. Under the outgoing U.S. administration’s leadership, the CFPB has proposed limiting the ability of data brokers to sell certain sensitive personal information, including financial data and credit scores, phone numbers, Social Security numbers, and addresses. The proposal would bring data brokers under the same legislation, in place since 1970, that applies to credit reporting agencies, and would require data brokers to obtain explicit approval from an individual before trading in their financial data.

Rohit Chopra, the CFPB’s director, stated that “By selling our most sensitive personal data without our knowledge or consent, data brokers can profit by enabling scamming, stalking, and spying. The CFPB’s proposed rule will curtail these practices that threaten our personal safety and undermine America’s national security.”

Since data brokers aren’t required to disclose the buyers of data and the type of data being bought and sold, the CFPB’s statement expresses concern about the technological ease with which bad actors can obtain sensitive information on millions of people.

There are lessons to be drawn from the history of financial deregulation and the 2008 financial crisis.

Memories can be short, and reducing financial regulations could lead to the same types of problems that resulted in the collapse of major global banks in 2008. It could also lead to additional problems, fuelled by technology that has become widespread since the 2008 implosion and that has allowed data brokers to buy and sell financial information on Americans and citizens of many other nations.

The CFPB was established to protect U.S. consumers in response to the 2008 worldwide financial crisis. That crisis was caused by years of lax lending practices of financial institutions that issued loans to borrowers who couldn’t repay them. Newly-issued loans, sometimes referred to as NINJA loans because they were made to borrowers who had “No Income, No Jobs, and no Assets,” were sold by financial institutions to investment funds which were then widely sold to individual and institutional investors.

The story of the collapse of Lehman Brothers, as told in one of many documentaries.

The rate of borrower defaults steadily increased until it became clear that financial institutions and investors were incurring substantial losses. The collapse in 2008 of Lehman Brothers, the fourth largest investment bank in the U.S., triggered a crisis of confidence that spread throughout global banking systems and led to the U.S. government’s emergency establishment of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Under TARP, the government took temporary control of major financial institutions as well as some manufacturers, including General Motors.

If financial regulations are once again reduced, what measures will prevent a repeat of the practices that led to the 2008 financial crisis and that could now also expose consumers to bad actors acquiring their financial data to perpetrate fraud, stalking, domestic and other violence, blackmail, and other crimes? Data is easily and inexpensively acquired and, as the CFPB notes, “Countries of concern, like China and Russia, can purchase detailed personal information about military service members, veterans, government employees, and other Americans for pennies per person.”

History shows that the cost of inaction can be high. The U.S. Treasury reports that TARP disbursed a total of $443.5 billion in emergency funding, most of which was recouped over the following fifteen years from asset sales, dividends, and interest, leaving taxpayers with a final cost of $31.1 billion.

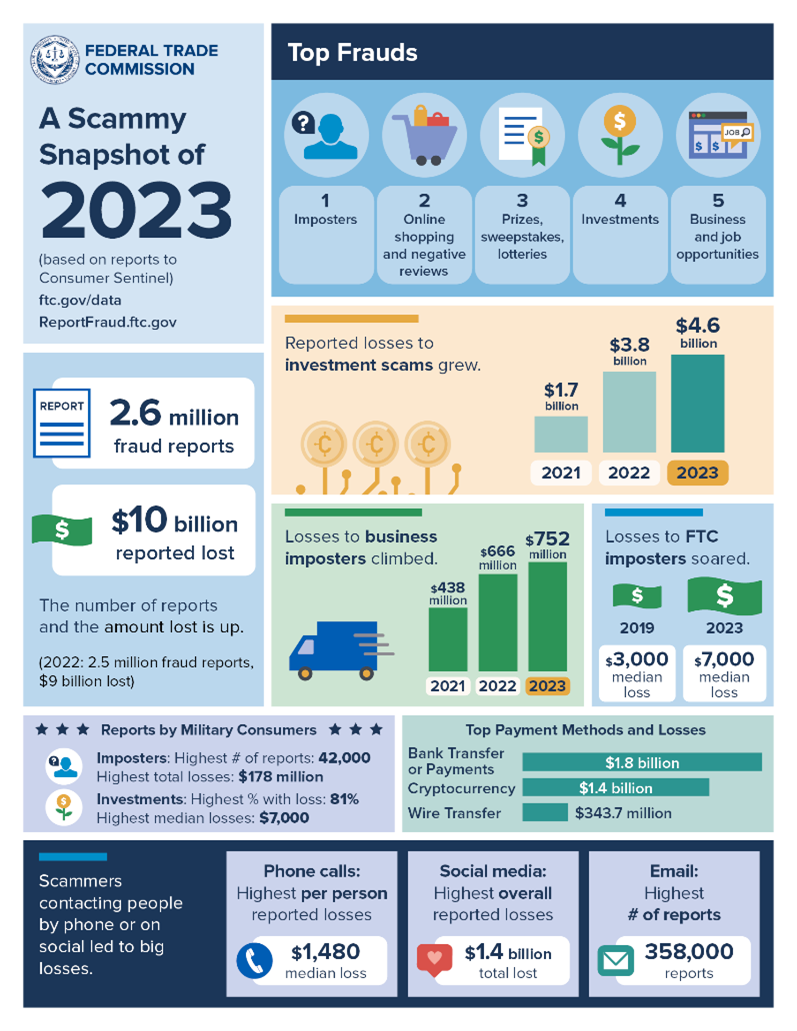

Image from U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

Many people suffered losses from the 2008 financial collapse. Large numbers of homebuyers who had been enticed by easily obtained loans lost their homes to foreclosure after defaulting on mortgage payments. Individual and pension fund investors in the funds that had bought the loans from the banks lost, in some cases, their entire investment. Other types of losses are now on the rise, with the U.S. consumer watchdog Federal Trade Commission reporting that Americans lost over $10 billion to fraud in 2023. The CFPB’s regulatory proposals aim, in part, to constrain further losses to fraud from the unscrupulous use of financial data acquired from data brokers.

It’s a fundamental responsibility of governments to ensure justice for citizens.

The paths to injustice from the abuse of technology and data are many, especially for vulnerable people who lack financial or computer literacy. What constitutes justice for consumers, however, is not always in the economic interests of buyers and sellers of data and other powerful people who control access to financial capital.

Marc Andreessen, pictured in 2013. Image: by JD Lasica, on Wikipedia.

As the Washington Post reports, Musk’s post on X calling for the CFPB’s deletion was in response to a podcast statement by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen that the CFPB is “terrorizing financial institutions.” The Washington Post notes that a company called LendUp Loans, in which Andreessen’s firm had invested, was shut down in 2021 by the CFPB under allegations that it had “misled customers about its short-term, high-rate loans and overcharged military service members.”

If governments don’t protect consumers, who will?

A report commissioned by the Canadian government, entitled Tracking the surveillance and information practices of data brokers: A systematic review, notes that “Currently, there are no international laws governing data brokers. Although organizations like the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), IARC Data Protection Policy and the UN Principles on Personal Data Protection and Privacy provide privacy best practices, data brokers are not obligated to follow them.”

As a minimum, governments could require disclosures from data brokers about their trading activities, to bring the industry out of the shadows. There’s a common saying that “sunshine is the best disinfectant,” and perhaps shedding more light on the buying and selling of our sensitive financial data will lead to widespread calls for governments to ensure that data subjects – you, me, and practically everyone else – are on a more level playing field with data brokers.