By James Myers

Our relationship with commercial artificial intelligence, including chatbots like ChatGPT and the AI applications underpinning virtual reality, is a trade. In exchange for the AI’s speed and functional power, we give up the right to future profit from the marketing of our own data and, with generative AI (GenAI), we risk giving up our capacity for imagination and independent thinking.

In fact, Fast Company reports that a new app called Verb, by youth polling company Generation Lab, is offering 18- to 34-year-olds just $50 (sometimes more) per month to track all of their online actions. The data is then sold for market research and advertising targeting. “By installing a tracker that monitors what they browse, buy, and stream, Verb creates a digital twin of each user that lives in a central database. From there, companies and businesses can query the data in a ChatGPT-like interface, and get a more accurate picture of consumer preferences than they would get even from a room full of Gen Zers.”

Under these terms of trade, how can young people acquire the power of independent thought, and continue to develop and exercise it through their lifetimes, when they’re faced with algorithmic targeting and the lure of cost-free convenience from AI’s that encourage us to outsource our cognitive functions? The question of protecting human creativity, when GenAI can make it easy to create but more difficult to be creative, is gaining prominence, with a special concern for educating youth.

The challenge is compounded by a trend of declining IQs. In our January 2025 feature, Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking, we reported on a number of studies that point to a global cognitive decline resulting from reliance on AI, reducing attention and practising of crucial judgment skills.

Microsoft Research reports on how generative AI reduces critical thinking.

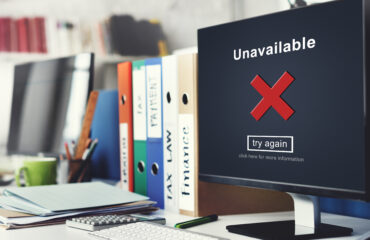

This February, a team of seven scientists with Microsoft Research, in Cambridge, UK, published a paper entitled The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers (see pdf). The researchers surveyed 319 knowledge workers on when and how they applied critical thinking in using GenAI, and when and why GenAI affected their critical thinking.

The survey revealed that “confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking.” When knowledge workers employ GenAI, they reported a change in their role, shifting from creation to verifying information, integrating responses, and overseeing tasks.

A significant majority of respondents also reported a perception of using “less” or “much less” cognitive effort when working with a GenAI tool compared to performing the task without GenAI assistance. Applying six categories to define critical thinking, the following table graphically displays the survey results, with the dark and light blue portions of the bars indicating the proportion of workers who felt that they applied less or much less effort in knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, and synthesis of results. Interestingly, there was a lower difference in the cognitive effort required for subjective evaluation of the outcomes.

Graph from Microsoft Research report The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers.

The Microsoft Research study found that participants were motivated to enact critical thinking while using GenAI tools for work by a desire to improve the quality of their work, avoid negative outcomes, and improve skill development. Factors weighing against critical thinking included time pressures and lack of ability, when participants felt they lacked either the time or skills to improve on the GenAI output.

It’s important to know what works – a task that AI can help with – but it’s also critically important to know what does not work.

The effects of automation have long been a concern. The researchers referenced a 1983 study by Lisanne Bainbridge who observed that “a key irony of automation is that by mechanising routine tasks and leaving exception-handling to the human user, you deprive the user of the routine opportunities to practice their judgement and strengthen their cognitive musculature, leaving them atrophied and unprepared when the exceptions do arise.”

Marvin Minsky, pictured in 2008. Image: Wikipedia.

The problem of weakening cognition can be compounded by lack of awareness of the limitations of one’s own knowledge. In a 1994 article, computer and cognitive scientist Marvin Minsky suggested that while expertise is often evaluated in terms of a person’s knowledge of what does work, it is just as important to assess it in terms of the person’s “negative expertise,” which is their knowledge of what does not work. Minsky wrote, “In order to think effectively, we must ‘know’ a good deal about what not to think!”

A study by computer scientist James Prather and co-authors, published in May 2024 under the title The Widening Gap: The Benefits and Harms of Generative AI for Novice Programmers, interviewed a group of new programmers who had participated in a series of 21 lab sessions where the researchers observed their eye movements and other actions.

The researchers found “an unfortunate divide in the use of GenAI tools between students who accelerated and students who struggled. Students who accelerated were able to use GenAI to create code they already intended to make, and were able to ignore unhelpful or incorrect inline code suggestions. But for students who struggled, our findings indicate that previously known metacognitive difficulties persist, and that GenAI unfortunately can compound them and even introduce new metacognitive difficulties.”

Metacognition is the act of thinking about thinking, and the paper’s authors noted that struggling students “thought they performed better than they did, and finished with an illusion of competence.” The study’s authors propose interventions to teach students about the use and limitations of GenAI, and how to apply critical thinking. For example, they suggest that for students who are struggling to construct and document logical arguments and processes, GenAI could be used “for individualised, content-focused feedback.”

Image by Gerd Altmann, Pixabay.

Software coding is at the frontier of the contest between human creativity and the convenience of AI.

A handful of giant technology companies like Microsoft, OpenAI, and Google are developing powerful and versatile AI applications that are rapidly gaining traction in education, the workplace, and everyday use. An example with consequences for both work and learning is the increasing capability of GenAI for software coding. Human coders traditionally learned algorithms and programming languages to develop, debug, and document software for a particular context, but generative AI is now being used for a significant portion of that work.

The added speed and processing of GenAI has made it increasingly prevalent in software coding, providing employers and human coders with a competitive advantage in a rapidly changing global economy.

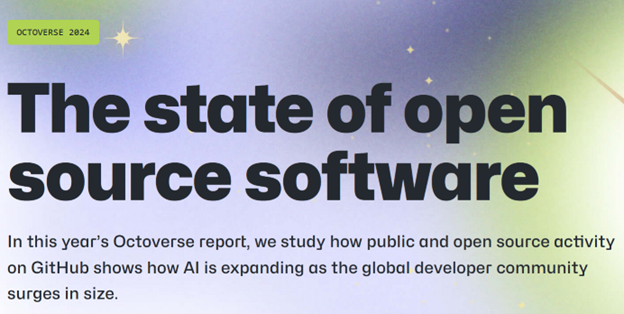

The Octoverse 2024 report highlights AI’s rapid melding with human coders. Image: Github

According to the GenAI named Claude, some industry surveys indicate that between 40-60% of developers consistently employ coding tools like GenAI, with debugging and code completion being the most common uses. (When prompted, however, Claude was unable to cite the source of its information on GenAI’s prevalence).

Millions of software developers actively use GitHub, which is Microsoft’s platform for developers to create, store, manage, and share their code. The GitHub Education program has more than 7 million participants, and the company reports “a surge in global generative AI activity.” In 2024, GitHub experienced an annual increase of 59% in the number of contributions to GenAI projects, and a 98% increase in the total number of projects.

GitHub usage and growth statistics, from the company’s 2024 Octoverse report.

The growing dominance of AI in coding has required a change in workplace and educational practices. It has also introduced new potential, for example in the process known as vibe coding in which a user describes a problem in a few sentences to a large language model, which then generates software to address the issue. This reduces the need for manual coding, and allows users to focus on guiding, refining, and testing the AI’s product.

It is now more important than ever for human users to understand the correct ways to prompt an AI for a particular task, and to share best practices. The role of testing automatically generated software, and governance structures to guard against unethical applications, are now in greater focus with the goal of ensuring human input remains in the software development loop.

How can GenAI’s trajectory be changed to promote independent thinking and creativity?

The profit motive of commercialized GenAI channels users to standardization and speed at the expense of the more burdensome and slower – but far more rewarding in its potential – process of human creativity.

In its recent feature edition on creativity, the MIT Technology Review spoke with Mike Cook, a computational creativity researcher at King’s College London. Cook observed that before GenAI produces an image or video, the software typically edits the user’s prompt with dozens of hidden words to generate an image that will appear more polished. Noting that the software serves up not what the user wants but what its designers want, Cook stated, “Extra things get added to juice the output. Try asking Midjourney [a GenAI] to give you a bad drawing of something – it can’t do it.”

Implicit in Cook’s statement is that human creativity is based, at least in part, on the contrast of opposites over time. We judge what is subjectively “good” in comparison to “bad,” whereas the machine struggles with the process and has no independent concept of the meaning of time and qualitative assessments like good and bad.

The airplane, which has transformed the world, was the creative invention of Orville and Wilbur Wright. Wilbur is shown here, on October 24, 1902, piloting one of their airplanes. Image: Wikipedia.

AI can be used to enhance the great human power of creativity.

“Co-creativity,” or more-than-human creativity, is emerging as one potential path for AI not to replace but instead to augment human creativity.

Co-creativity advocates are developing methods for AI to support or encourage the user’s capacity for reflection, giving the human both time and information for a slower-paced deliberative process. While reflection doesn’t have the advantage of speed, it has access to something far more powerful. Reflection often results in the questioning of long-held assumptions and a re-thinking of approaches to particular problems – both of which produce the benefit of invention. Without a supply of the vast range of human imagination, machines can’t invent.

For instance, instead of attempting to produce a flawless image using hidden algorithmic instructions added to a user’s prompt, a GenAI could deliver exactly what the user’s words specified (questioning when unclear). The flaws and mistakes could allow users to reflect on how better to describe the images in their heads, and learn to ‘paint with words’ when physical painting skills or time are lacking.

This is an example of “democratization” of a specialized task such as painting, allowing many others who aren’t skilled painters to produce original, creative work. Democratization of software coding is one of the benefits of GenAI, according to IBM.

In IBM’s October 2024 AI in Software Development report, the company warns of a number of risks associated with the use of AI in software development, including bias, overreliance, security, and lack of transparency. Providing the overall conclusion that AI is improving software development, the company (which has software development tools available on GitHub) enumerates five other benefits in addition to democratization.

To IBM, these benefits include automation of repetitive tasks, improved software quality (in the company’s view), faster decision-making and planning, and enhanced user experience and personalization.

Far greater benefits are just around the corner, if we follow the right path. Creative computing is an emerging area of study that’s an example of one path that could produce an incredible value of future inventions. For example, the University of the Arts London offers courses in creative computing to develop skills in machine learning and creativity, human computer interaction, visualization and sensing, and software development for digital creative industries. King’s College London promotes its digital creativity, with programs in creative digital skills and human centred computing.

Aiming to broaden creativity with the use of AI, King’s College London’s Creative AI Lab is collaborating with the Serpentine Gallery in providing help to cultural institutions, artists, engineers and researchers engaging with AI and machine learning for the benefit of the wider cultural sector.

GenAI: will it be a holistic technology, or a prescriptive technology?

Dr. Ursula Franklin (1921-2016). Image: Wikipedia

Physicist, metallurgist, and humanist Dr. Ursula Franklin (1922-2016) famously delivered a series of lectures in which she classified technology in two fundamental categories.

One category is prescriptive, when human users are unable to change the technology’s particular functions and therefore have to adapt to the technology’s particular requirements. Prescriptive technology can be used for human invention, however the other fundamental category, holistic technology, can supercharge innovation and creation.

The advantage of holistic technology, to the human user, is that the technology is capable of adaption to a particular user’s particular needs. This frees the human to be even more creative, providing the power of expression – as in the ‘painting by words’ example of technological democratization – and providing full ability to explore many unthought of paths of development.

(In our Philosophy of Technology series, The Quantum Record featured Ursula Franklin’s philosophy in our inaugural feature Time and Our Technological Mindset, and presented her theory of prescriptive and holistic technologies in Two Technological Choices for a Future as Good or as Bad as We Can Imagine.)

In software development, which is at the brink of the divide between human creativity and algorithmic convenience, the choice seems to be one of pursuing either a prescriptive or a holistic path to the future.

Our choice of paths is particularly crucial for young people to become independent, creative thinkers. We need to ask questions, to make a reasoned choice before reasoning is taken away from us.

One example of a question we could ask is whether it’s best to add a burden of hidden algorithms to a user’s prompt for a GenAI image, or better still to allow users to witness the unaltered result of their own creativity.

Hidden algorithms are a type of prescriptive technology, whereas a holistic technology would reflect a user’s unique creative skills. The holistic technology would allow the user to experience what Marvin Minsky called “negative expertise,” in order to advance expertise and knowledge.

If the short-term profit-making incentive of prescriptive technology were replaced with the long-term profit potential for holistic technology to free us for invention, creativity might very well flourish quickly. Creativity is perhaps our greatest power to protect the young, and defend independent thought, in the Age of GenAI.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Everything Has a Beginning and End, Right? Physicist Says No, With Profound Consequences for Measuring Quantum Interactions

- Cleaning the Mirror: Increasing Concerns Over Data Quality, Distortion, and Decision-Making

- Not a Straight Line: What Ancient DNA Is Teaching Us About Migration, Contact, and Being Human

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies