By Mariana Meneses

Are we becoming smarter, or are our minds slowly dulling under the weight of digital life? As average IQ scores begin to slip, and as phrases like “brain rot” take root in public consciousness, researchers, educators, and technologists are scrambling to understand how environmental and technological shifts are reshaping the way we think. This article traces the scientific and cultural conversation around cognitive decline in the age of algorithms.

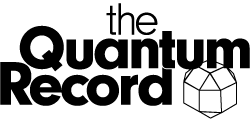

Attention is fundamental to learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. Recent research shows that strengthening attention can enhance cognitive control, leading to better learning outcomes and greater adaptability to complex tasks. But while some activities reinforce attention and cognitive flexibility, other trends raise concerns about their erosion. More specifically, recent studies suggest that the growing reliance on AI tools may be accelerating cognitive shifts.

Example of the relationship between attention, cognitive control, and learning performance. Credit: Chan et al (2020).

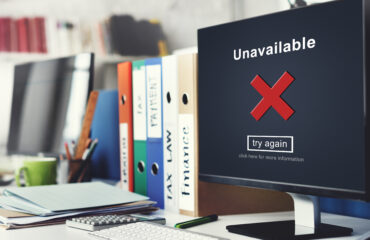

A 2025 survey by Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University found that workers who heavily trust AI assistants engage in significantly less critical thinking, often completing tasks with little to no independent scrutiny. Researchers warned that while AI can improve efficiency, it may also erode the “cognitive musculature” necessary for critical judgment—raising concerns about long-term impacts on problem-solving skills and attention spans.

Distribution of perceived effort (%) in cognitive activities when using a GenAI tool compared to not using one. Credit: Lee et al (2025).

A 2018 study conducted by Norwegian researchers Bernt Bratsberg and Ole Rogeberg revealed a steady decline in IQ scores among men born after 1975, reversing the upward trend known as the “Flynn effect” that characterized much of the 20th century. Analyzing IQ data from brothers born between 1962 and 1991, the researchers found that the decline could not be explained by genetic factors, as even siblings from the same families showed significant score differences.

Professor James Flynn (1934-2020), photographed in October 2009. Flynn was a moral philosopher and intelligence researcher; he taught political studies and championed social democratic politics throughout his life (Wikipedia). Image: Alan Dove.

This challenges the longstanding assumption that intelligence is predominantly inherited and counters the “dysgenic fertility” theory, which posits that less intelligent individuals having more children lowers the average IQ of a population. Instead, the study points to environmental influences such as changes in education, digital media consumption, and reduced reading time. Experts suggest these shifts reflect evolving cognitive demands in a technology-driven world and call for updated approaches to measuring and fostering intelligence.

Named after intelligence researcher James Flynn, the Flynn effect refers to the steady rise in average IQ scores observed over successive generations, particularly throughout the 20th century. This upward trend has been substantial enough to render older IQ test norms outdated over time. A large-scale meta-analysis of over 280 studies confirmed that IQ scores have increased by roughly 2 to 3 points per decade, a pattern that remained consistent across different age groups, test types, and performance levels (Trahan et al., Psychological Bulletin, 2014).

In IQ scoring, the average is set at 100, with a standard deviation of 15 points. This means that a gain of 2 to 3 points per decade is modest for any individual but becomes significant across populations over time. (Brainly)

What, then, caused the 20th century rise and why is it reversing? Drawing from their analysis of over 730,000 Norwegian men, Bratsberg and Rogeberg concluded that both the increase and the decline in IQ scores originate from environmental factors operating within families. This finding rules out genetic and demographic explanations and highlights the role of shifting societal conditions. Improved education, nutrition, and public health likely fueled earlier gains, while the recent downturn may stem from stagnating educational quality, increased passive media consumption, and reduced cognitive engagement.

In other words, the same forces that once elevated population intelligence may now be contributing to its decline.

Adding to the complexity of recent IQ trends, new research suggests that the structure of intelligence itself may be shifting. A 2024 cohort study at the University of Vienna tracking IQ test results in German-speaking populations from 2005 to 2024 found that while scores have continued to rise in some cases—especially among individuals with initially lower scores—the overall coherence between different cognitive abilities has weakened.

In technical terms, the study observed a decline in the “positive manifold,” which refers to the pattern where people who perform well in one cognitive skill tend to perform well across others—a relationship that reveals the strength of an underlying general intelligence factor. This suggests that while people may still be improving in specific domains, those improvements are less likely to overlap with gains in other areas of intelligence. In effect, the population may be becoming more cognitively specialized or differentiated, a trend that could help explain the inconsistencies and reversals observed in recent Flynn effect data.

The rise of AI has deepened these concerns.

In 2024, Forbes reported that AI may also be quietly dulling our cognitive edge. Unlike earlier technologies—like calculators or spreadsheets—that assisted without replacing thought, AI increasingly performs the thinking for us, potentially reducing our opportunities to practise critical reasoning.

In education, studies show that students who rely on generative AI perform worse on tests, suggesting a weakening of problem-solving and conceptual understanding. In the workplace, concerns have emerged that constant reliance on AI tools may erode employees’ mental agility and decision-making capabilities. As algorithms take over tasks that once demanded human judgment—from diagnosing patients to managing investment portfolios—we risk losing not just skills, but confidence in our own reasoning.

In this sense, some experts argue that the key is not to reject AI, but to use it as a cognitive partner—one that explains, augments, and invites deeper thinking rather than replacing it.

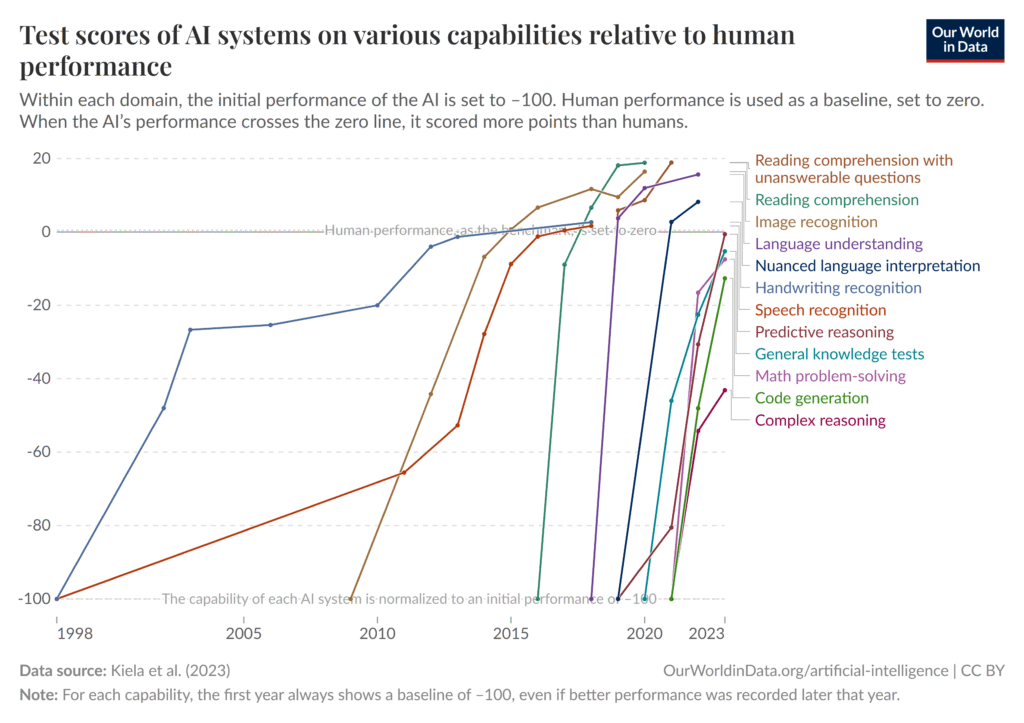

“Test scores of AI systems on various capabilities relative to human performance. Human performance is used as a baseline, set to zero. When the AI’s performance crosses the zero line, it scored more points than humans.” Credit: Kiela et al. (2023) / Our World in Data.

Building on these concerns, a 2025 study by Michael Gerlich, from the SBS Swiss Business School, adds empirical weight to the idea that AI use may come at a cognitive cost. Through surveys and interviews with over 600 participants across age groups and educational backgrounds, the study found a significant negative relationship between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking skills. This effect was especially pronounced among younger individuals, who reported higher reliance on AI and scored lower on measures of independent reasoning.

The study highlights cognitive offloading—the delegation of mental effort to external systems—as a key factor mediating this decline. While some offloading is natural and even beneficial, Gerlich’s findings suggest that over-reliance on AI may reduce opportunities for practising complex thought. Interestingly, individuals with higher levels of education tended to retain stronger critical thinking abilities despite AI usage, pointing to the protective role of deeper learning.

“Brain Rot”: Oxford’s 2024 Word of the Year, as Voted by the Public

In 2024, “brain rot” was named Oxford’s Word of the Year following a public vote that drew over 37,000 participants. The phrase, which gained widespread traction across social media—particularly among Gen Z and Gen Alpha—describes the perceived decline in mental sharpness caused by excessive exposure to low-effort digital content. Often used with humor or irony, the term doubled as a self-aware critique of the very platforms fueling its rise. Its usage surged by 230% over the year, reflecting growing unease around attention spans, youth mental health, and the cultural impact of viral absurdities and memes.

“The first recorded use of ‘brain rot’ was found in 1854 in Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden, which reports his experiences of living a simple lifestyle in the natural world. As part of his conclusions, Thoreau criticizes society’s tendency to devalue complex ideas, or those that can be interpreted in multiple ways, in favour of simple ones, and sees this as indicative of a general decline in mental and intellectual effort.” (Oxford University Press)

The choice marks a shift from celebrating internet-born slang to spotlighting its cognitive and cultural consequences. As Scientific American noted, the term “brain rot” captures not just a present-day concern but a recurring cultural fear that modern life is gradually dulling our minds into passivity. In a digital age shaped by algorithmically optimized content and constant low-effort stimulation, that fear feels more relevant than ever.

While the popularity of the term “brain rot” reflects genuine cultural unease, not all researchers agree it signals a cognitive or mental health crisis. Psychologists Dr. Poppy Watson and Dr. Sophie Li from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, caution against jumping to conclusions, arguing that current evidence linking digital content consumption to diminished focus or declining mental health is mostly correlative, not causal. Though excessive screen time has been associated with symptoms like anxiety and depression, longitudinal studies suggest the direction of this relationship remains unclear.

According to the researchers, broader structural factors—such as poverty, poor diet, and access to education—may play a far more significant role in cognitive health than social media alone.

Some experts frame today’s anxieties as part of a recurring cycle of technological panic, echoing historical fears that writing, the printing press, and television would reduce intelligence and weaken critical thinking. But what sets the digital age apart is the algorithmic personalization of content, fragmenting shared reality and subtly shaping behavior in ways that are increasingly difficult to trace. The challenge, then, may lie less in the technology itself and more in how we choose to live with it.

In this moment of rapid integration, keeping human intelligence—not just artificial—at the center of the equation may be the most strategic decision of all. Studies like Gerlich’s highlight the need for educational strategies that foster critical thinking and reflective engagement with technology, rather than passive dependence.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies

- Does Time Flow in Two Directions? Science Explores the Possibility—and its Stunning Implications

- Do We Live Inside a Black Hole? New Evidence Could Redefine Distance and Time

- What’s Slowing the Expansion of the Universe? New Technologies Probing Dark Energy May Hold the Answer

- The Corruption of Four-Dimensional Humanity with Two-Dimensional Technology