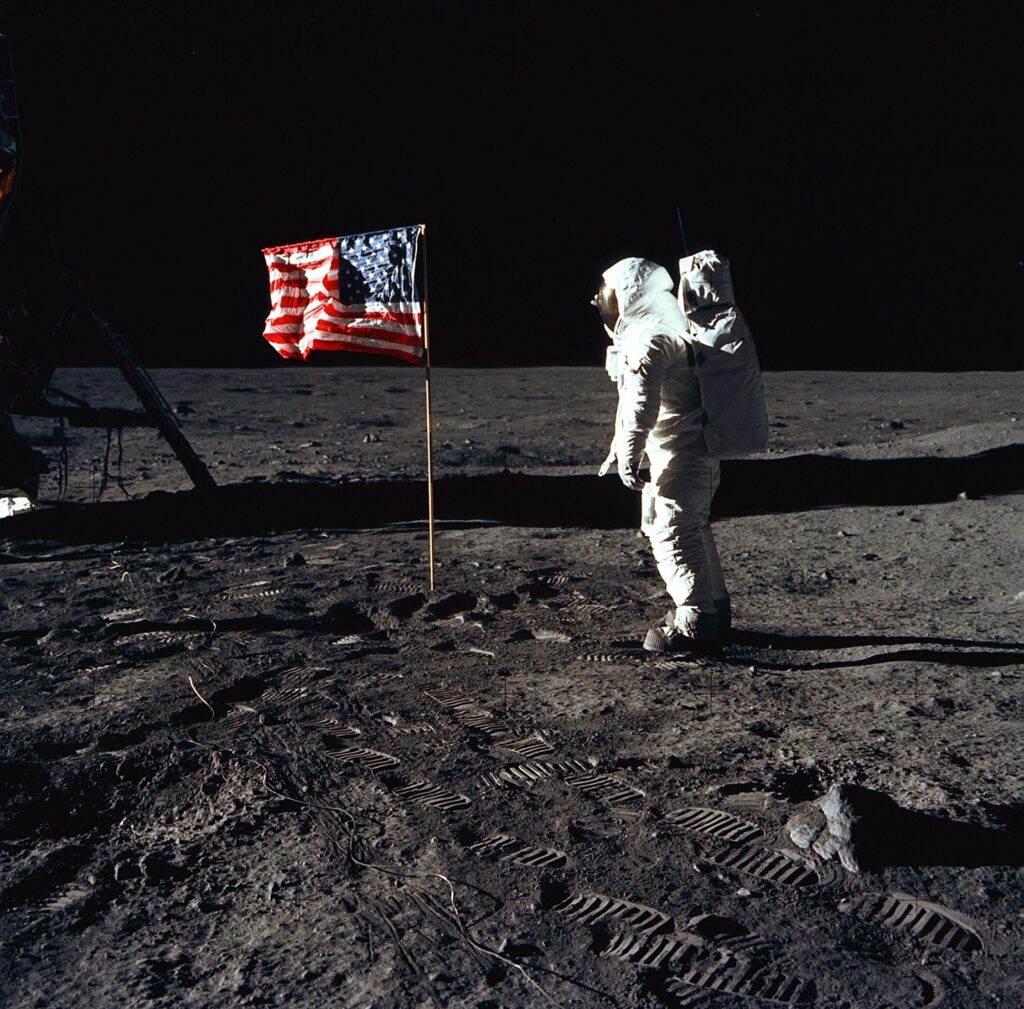

Astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin walks on the Moon, in 1969. Image: NASA

By James Myers

Time might seem to move very quickly in our technological era, but as we celebrate recent human achievements in science – like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) that allows us to look back over 13 billion years in time – we should remember it wasn’t that long ago that we were still striving to reach the Moon.

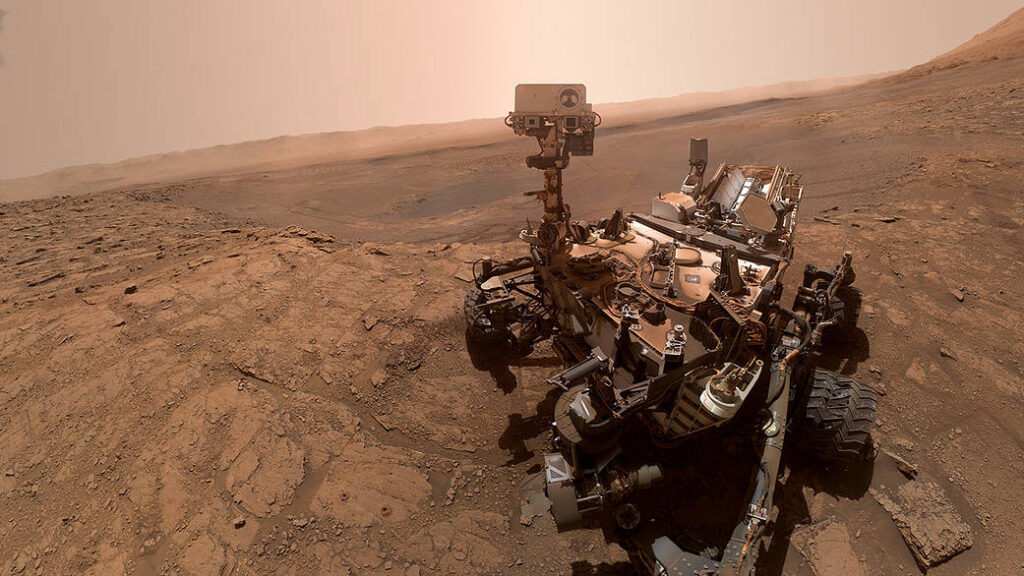

NASA Curiosity Rover on Mars, in 2019: only 50 years after a human first set foot on the Moon, we had begun to explore our planetary neighbour. Image: NASA

It was only 54 years ago, with NASA’s Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, that a human first set foot on soil somewhere other than Earth.

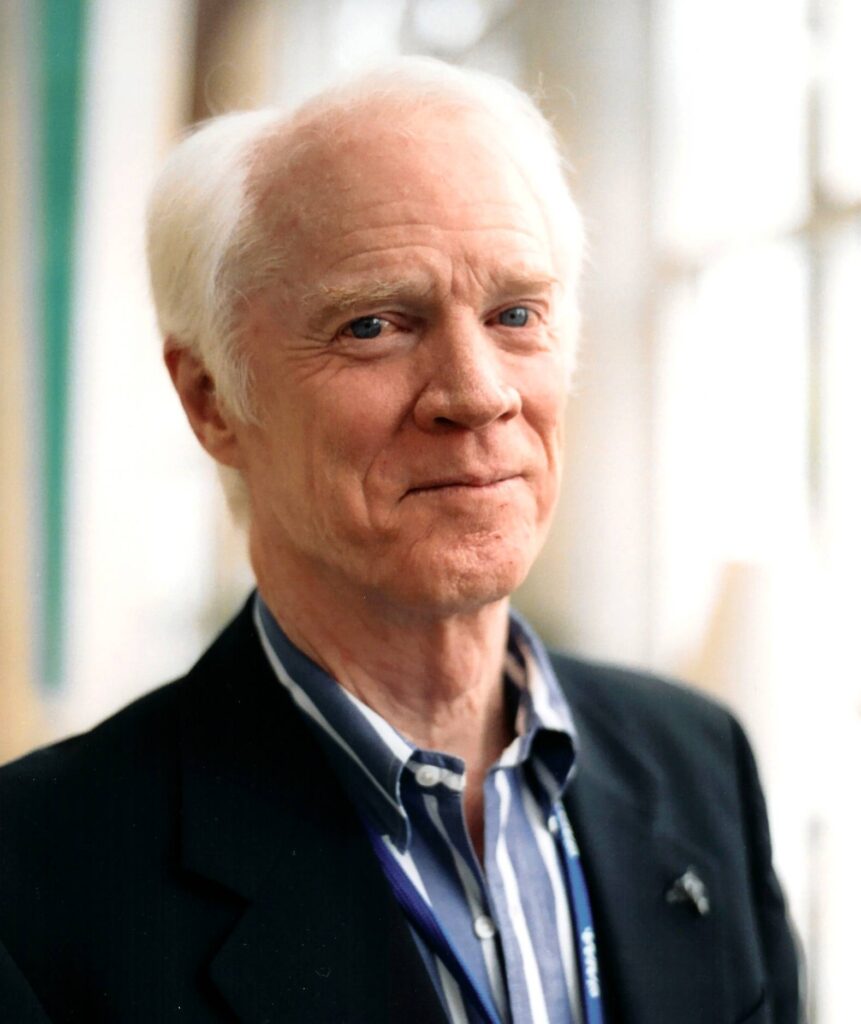

In preparing for the Moon landing, Russell (Rusty) Schweickart was one of three astronauts in the Apollo 9 mission that, for 10 days in March 1969, tested the technology of the Lunar Module to descend to the Moon’s surface and return its human cargo to orbit.

The First Science Was Citizen Science

Russell “Rusty” Schweickart, Apollo 9 astronaut. Image: Wikipedia

Until 54 years ago, there were no experts on lunar landings or on much of the technology required to achieve the feat.

Expertise emerged from the combined efforts not only of astronauts like Schweickart, but of the many scientists, engineers, leaders, and everyday citizens who worked in the industries that created and manufactured the necessary technologies. The Moon landing, the JWST, and many other human accomplishments, would not have been possible without the support of citizens who lend their time and effort to science.

When the first humans appeared on Earth, there was no science and there were no experts. Knowledge accumulates over time, with collaboration between scientific knowledge of “how” and citizens who wonder “why,” together pushing the boundaries of knowledge to new frontiers. In 1969, Schweickart was an example of the combination of “how” and “why”, as a pioneer in a collaborative effort that has opened new vistas for space exploration and planetary defence ever since.

Schweickart’s contribution to science as pilot of the Apollo 9 Lunar Module didn’t end in 1969, but continues to this day.

One of Schweickart’s most important legacies, many of which are in this video of his career highlights, may prove to be the B612 Foundation, which he co-founded with fellow astronaut Ed Lu in 2002 with the goal of protecting our planet against an asteroid strike.

Defending Earth is a Public Priority Requiring Collaboration of Citizens and Scientists

The mission of the B612 Foundation is one that the public strongly endorses. A new Pew Research Center survey of American attitudes toward space exploration and policy reports that 60% of 10,329 adults surveyed say the first priority should be to “monitor asteroids, other objects that could hit the Earth.” This public priority is not reflected in NASA’s budget, which provides a relatively small proportion of funding for planetary defence.

We know the dangers of asteroid strikes, because we continue to witness their destruction.

The Tunguska impact in 1908 flattened 2,150 square kilometres of forest in Siberia. In 2013, a meteor crashed into Earth near Chelyabinsk, Russia with no warning, and caused significant property damage. And, of course, it was an asteroid strike 66 million years ago near Chicxulub, Mexico, that is believed to have brought the reign of the dinosaurs and most other life on Earth to an end. The Chicxulub asteroid crater was discovered only in the decade after Schweickart’s Apollo 9 mission.

Nineteen years ago, in 2004, there was a brief time of planet-wide concern of the very real risk that an asteroid named Apophis would strike Earth in 2036, a short thirteen years from now. NASA and other space agencies continue to track other threatening Near-Earth Objects (NEOs), and it is expected that the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will observe more NEOs when it begins operation in a year.

“We now have the power to slightly redesign the solar system in order to enhance the survival of life on Earth, and to join, at some point, a future community of life in the universe.” – Rusty Schweickart, referring to NASA’s successful 2022 DART mission to test technology to deflect an asteroid.

While asteroid-deflection technology was successfully tested by NASA in 2022, much remains to be done to enhance early detection, plan for, and mount a successful planetary defence with little warning.

It may be another 66 million years that a planet-destroying asteroid strikes Earth, but it could also happen in a matter of days.

That’s the thing about asteroids – they’re difficult to detect and track, and often, as in Chelyabinsk, they arrive with no warning. Wisdom dictates against complacency, in such cases, because investing in defensive measures can prevent catastrophe and ensure that human time will continue. Schweickart, the B612 Foundation that he helped to launch, and many other citizen and science organizations like B612, are powerful advocates against complacency.

Technological Priorities and the Search for the Unknown

Humanity faced many unknowns in space exploration and technology in the 1960s.

The pioneering mission of Schweickart and fellow astronauts David Scott and James McDivitt occurred a scant seven years after U.S. President John Kennedy announced, in September 1962, the intention to land a human on the Moon before the decade was finished. Kennedy’s vision became reality in such a short time, thanks in no small measure to the contributions of many thousands of scientists and citizens supporting the effort.

Apollo 9 crew members David Scott, James McDivitt, and Rusty Schweickart. Image: Wikipedia

Kennedy’s famous “moonshot” speech launched what can be seen as perhaps the most prominent citizen science project of recent times, spawning the development of technologies we now routinely use but which were, 54 years ago, an immense challenge.

The Moon landing project was driven, in part, by national pride to beat the Soviet Union in a milestone for humanity, which Kennedy acknowledged. However, he highlighted the greater, collective goal of the effort.

John F. Kennedy’s September 12, 1962 “Moonshot” address at Rice University: “We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. … I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.”

Kennedy’s speech inspired a nation to imagine the human potential: “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we’re willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others too.”

The knowledge developed for the successful Moon landing was the product of human efforts over a very long time.

The connection between time and knowledge is inescapable, as Kennedy pointed out at the outset of his speech when he challenged listeners to condense 50,000 years of recorded human history into 50 years, placing our limited time in existence on a far vaster cosmic scale. As he observed, on the cosmic time scale, it was only a month ago that electric lights were first introduced.

The technology that led to the success of the moon landing is, of course, no longer in use and seen only in museums as part of human history. That’s because knowledge has continued to build on what Schweickart and others did in 1969, as a result of which today’s technology far exceeds the capacity of what might now seem like primitive but effective tools used to reach the Moon 54 years ago.

Today’s Youth are the Scientists of Tomorrow

With curiosity for the unanswered questions among today’s scientific achievements, today’s generation of youth has the ability to take knowledge further into the unknown in the future, charting new potential for human existence. Today’s youth are citizen scientists, and will be the trained scientists of tomorrow, a fact that Schweickert celebrated in a speech acknowledging the announcement of a prize in his honour by the B612 Foundation.

Rusty Schweickart’s spacewalk, the first extravehicular activity (EVA) of the Apollo program. Image: rustyschweickart.com

The Schweickart Prize for Planetary Defense is an annual prize that will be awarded to a young researcher for exceptional contributions to the field of asteroid science, research, and policy work.

Speaking at a press conference, Schweickart emphasized the collective effort of science between generations: “One of the main reasons that I’m so excited by this is the possibility of stimulating many, many young people from around the whole planet to dedicate their lives to the extension of this great life experiment which we are all part of here on Earth.”

Rusty Schweickart. Image: rustyschweickart.com

Schweickart went on to express a philosophy that can serve to spark young imaginations with the wonders of science and a love for humanity.

“During my brief Apollo 9 spacewalk, while I was looking out at this incredibly beautiful, spectacular planet – I had 5 minutes with nothing to do, which is very unusual in space, but because of the failure of a camera I had that 5 minutes – and I said, “Let’s just be a human being here, not an astronaut, just be and let it all come in.”

And in that few moments that I had, it became very clear to me that I was not there because of me, I was there representing everyone else on this planet below me. I was, as I said at the time, a sensing element for humanity as we are moving out into space. And I realized that in fact I was, at that time, “us.”

We are this great experiment in our little local section of the universe, and we are about to be born into that larger cosmos. I later referred to that, and have referred to it since, as the process of cosmic birth.”

This edition of The Quantum Record features some of the scientists who are exploring the most important frontiers of knowledge with the help of citizen scientists.

Like Schweickart, today’s citizen scientists act as “sensing elements” for the future, adding their curiosity to expand the boundaries of knowledge.

Humanity’s place in the cosmic time scale will depend very much on our observational skills as “sensing elements” – all of us, and all who will follow us.

As Schweickart observed, asteroids do not recognize national boundaries, and “Where there is a planetary challenge, there must be a planetary response. And so one of the more subtle features of this entire endeavour of planetary defence is that it demands that we collectively, as individuals, as nations, as the public, come together to address this planetary challenge.”

Such a confrontation will force, as he observed, geopolitical, economic, communication, and trust-building decisions to address humanity’s scientific future.

We will all be, at the time Earth requires defending, citizen scientists.

James, a very interesting article. Keep them coming.