The interconnectedness of our universe transforms nuclear testing residue into a valuable tool to advance the conservation of whale sharks, an endangered species. Carol M. Highsmith.

By Mariana Meneses

Important scientific breakthroughs are sometimes made during the most violent and cruel historic periods.

The incentives for technological advancements during wartime have led to various discoveries that profoundly shaped modern life. The list is long and ranges from penicillin and the hepatitis B vaccine, to radar and satellites. Now, a breakthrough has arisen from the remains of nuclear bomb tests during the Cold War between the U.S. and Soviet Union that lasted for over 40 years following the end of the Second World War. As it turns out, this nuclear residue can help us uncover one gigantic ocean secret.

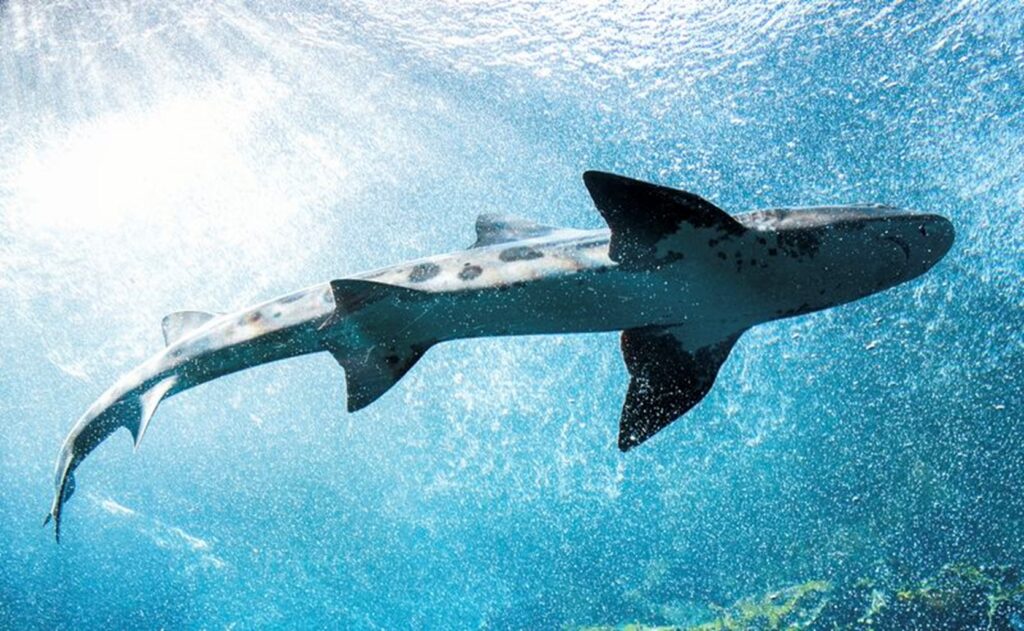

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the world’s largest fish, and they can grow up to 60 feet long.

These imposing marine creatures are recognized by their white-speckled and striped backs. As they age, they also gain stripes on their vertebrae, forming layers called growth bands. These bands are much like the rings in a tree trunk, so the older a whale shark is, the more bands it has. However, unlike trees, for which methods of determining age have long existed, decoding age from patterns in growth bands of whale sharks remained a challenge until recently.

In an unexpected turn of events, the mystery of how long these massive fish live was uncovered due to nuclear residue from the Cold War.

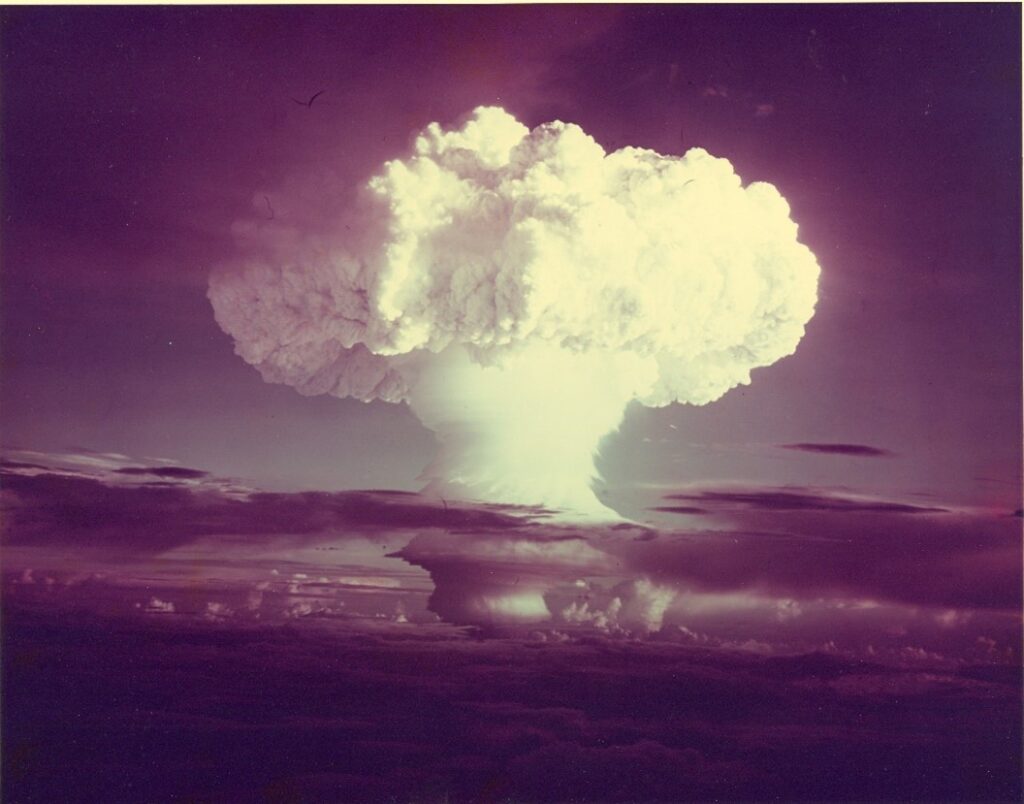

During that period, countries tested nuclear weapons by detonating them high in the atmosphere, which ended up doubling the amount of a particular isotope of carbon, called carbon-14, in the air. The spike in this radioactive form of carbon from these nuclear experiments accumulated in many living things, leaving behind a chemical signature. Eventually settling in the ocean, these radioactive atoms became embedded in marine animals, and, mostly through the food chain, made their way from the tiniest to the most gigantic creatures in the sea.

“Ivy Mike (yield 10.4 mt) – an atmospheric nuclear test conducted by the U.S. at Enewetak Atoll on 1 November 1952. It was the world’s first successful hydrogen bomb.” The Official CTBTO Photostream.

Although the accumulation of radioactive carbon in living beings is hardly something to commemorate, researchers believe this chain of events will now help conservation strategies.

These methods are highly dependent on accurate estimates of demographic factors, such as age and growth rates. Until recently, scientists could not agree on how long whale sharks can live, since it was not clear whether their vertebrae gain a new growth band each year or every six months. With the new discovery, researchers have concluded that whale sharks can live up to 50 years, with new bands forming annually.

In a paper published in 2020 in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, Dr. Joyce Ong, Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore and co-authors used a 20-year-old method to figure out shark ages using the carbon-14 in the cartilage of their skeletons. Originally developed by the study’s co-author, Dr. Steven Campana, from the University of Iceland, the method allowed the scientists to analyze vertebrae collected from two whale sharks, one found in Taiwan in 2007 and the other in Pakistan in 2012.

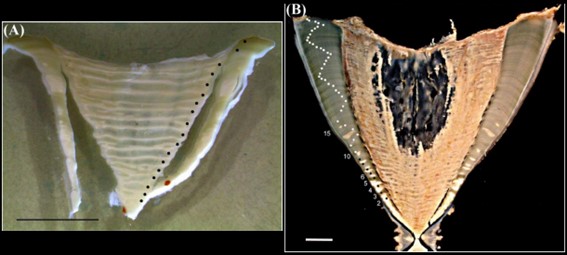

The chemical traces left by the Cold War-era nuclear tests allowed the scientists to identify “time stamps” in the bands of the vertebrae of the whale sharks.

The researchers estimated the time each growth band formed by matching the amount of carbon-14 in different growth bands with the known carbon-14 levels in surface seawater in different years. As a result, they concluded that bands generally grew a year apart. The whale shark found in Taiwan was about 35 years old when it died. The other one, found in Pakistan, had 50 growth bands, which meant it was 50 years old. While these sharks were about 10 meters long, these animals can grow up to about 18 meters, which suggests that the species’ lifespan can be much longer.

“It is really, really likely that there are older whale sharks out there, simply because we know there are much larger whale sharks,” said Dr. Campana.

Images of sectioned whale shark vertebrae with dots marking growth bands. Adapted from Ong et al, 2020.

The researchers also used growth-band counts to determine the ages of 18 other dead whale sharks, measuring from 2.7 to 6 meters in length and ranging from 15 to 25 years in age.

Based on this information, they could infer that these sharks generally grow about 20 centimeters per year. Dr. Campana said that, for conservation, “it makes a big difference whether they are fast-growing and short-lived, or slow-growing and long-lived,” since long-lived, slow-growing animals take longer to recover from population loss.

Biologist Allen Andrews advises that there are some limitations to the technique used in the study. The carbon-14 dating method has some intrinsic uncertainty, since radioactive carbon from nuclear tests did not spread evenly throughout the Earth’s oceans. Thus, for instance, if young whale sharks – which tend to “disappear” (i.e. scientists have a harder time tracking them) for an extended portion of their lives – spend much of their time deep underwater, they may not receive the same dose of carbon-14 as measured at the ocean’s surface.

In the future, scientists could further this research by tagging live sharks and then recapturing them, so they can measure their growth in between known periods.

Nonetheless, the importance of the research is unequivocal. “Real data from real animals adds a critical piece of information to how we globally manage whale sharks”, said Oregon State University shark specialist Dr. Taylor Chapple, who wasn’t involved in the study. Whale sharks are the biggest fish in the sea, and are an endangered species, facing threats from fishing and boat strikes – especially since the species is known to spend their days near the surface of the water, which puts them at high risk of injuries by human activities.

Whale shark populations may not recover from threats like overfishing as quickly as species with shorter life cycles.

“Long-lived animals like whale sharks almost certainly become mature at a relatively old age, and their populations are relatively slow to increase their numbers,” said Dr. Campana. According to Dr. Mark Meekan from the Australian Institute of Marine Science, who co-authored the study, since “whale shark populations take a very long time to recover from over-harvesting, (…) governments and management agencies must work together to ensure this iconic animal persists in tropical oceans – for both the future of the species and the many communities whose livelihoods depend on whale shark ecotourism.”

Information on the lifespan and growth rates of these majestic and endangered sea creatures could inform better conservation strategies.

Who would have thought, during decades of nuclear weapons testing, that one of the outcomes could lead to preservation of an endangered species? Well, probably nobody. Yet, the study by Dr. Ong and colleagues reminds us of how human science has not only the power to destroy, but also the power to learn from destruction.

Hungry for more information? Feast your mind on these recommended TQR articles:

- NeMO-Net Catalogues Coral Reefs Using Games: A Citizen Science Project

- Explore Tropical Africa From Home: A Citizen Science Project

- Ancient Technologies

- The Rising Power of Citizen Science: Enthusiasts Become Agents of Change