Where does consciousness come from? Image Source.

Where does the subjective experience of consciousness come from?

How is it that light entering the retina and activating the visual cortex ends up generating the conscious understanding of whatever reflected the light – whether it was a tree, a cup of coffee, the sunset, or a loved one? This mind-body problem, also known as the hard problem of consciousness, has motivated many debates over the years.

“This is quite a mystery since it seems that our conscious experience cannot arise from the brain, and in fact, cannot arise from any physical process,” says Dr. Nir Lahav, a physicist from Bar-Ilan University in Israel.

For a long time, scientists have tried to understand the origins of our conscious experience, but it has not been easy. The study of consciousness is very close to the study of reality itself. To illustrate it, let us consider a few questions.

When a tree falls and no one is there to listen, does it make a noise?

If every being with the ability to see vanished from Earth this second, would things still have colors and shadows? And if no one ever touched and smelled the flowers, would they have textures and scents? Would all that information (the colors, odors, textures and sounds) exist independently of observation?

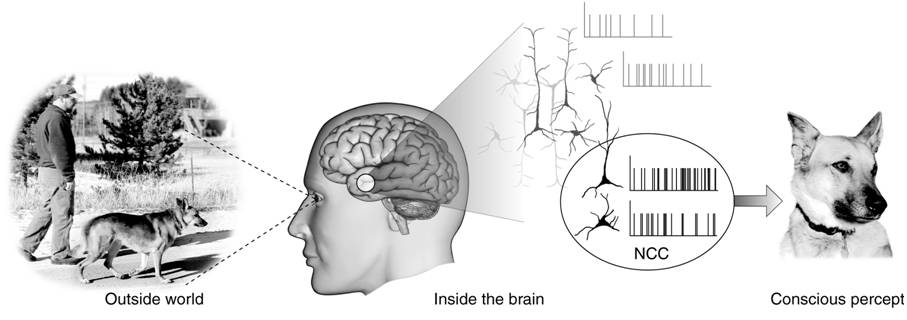

The conscious perception depends on the interpretation by the observer. Image Christof Koch.

Our perception depends on our relative positions as observers.

For instance, a dog would remember the colors of a rainbow differently than a human would, and you’ve certainly encountered situations when two honest people had completely distinct views of the same event. Differences in physical perspective are explained by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, and new research claims that this relativistic thinking may be precisely what we have been missing to solve the mystery of consciousness.

General theory of relativity: “Two observers moving relative to each other experience the world differently: Both measure the same speed of light. Both find the same physical laws relating distance, time, mass, etc. But, both measure different distances, times, masses etc.,” explains Dr. Richard Pogge, astronomy professor at Ohio State University.

Until recently, perhaps the most accepted, albeit often criticized, explanation of the phenomenon of consciousness was given by Integrated Information Theory (IIT).

Proposed initially in 2004 by Dr. Giulio Tononi, this theory has been enhanced over nearly two decades. According to it, consciousness should be understood in terms of information. The main idea is that consciousness can be measured mathematically as the “integrated information” of the system, or how good the system is at simultaneously distributing and processing information. In other words, consciousness could be described as the measurement or integration of information of the physical system that is being observed.

“But IIT has its problems,” explains Dr. Sabine Hossenfelder, physicist and science communicator.

“One problem with IIT is that computing [it] is ridiculously time-consuming. The calculation requires that you divide up the system you are evaluating in any possible way, and then calculate the connections between the parts. This takes up an enormous amount of computing power. Estimates show that even for the brain of a worm, with only 300 synapses, calculating [it] would take several billion years. This is why [these types of] measurements that have actually been done in the human brain have used incredibly simplified definitions of integrated information. Do these simplified definitions at least correlate with consciousness? Well, some studies have claimed they do. Then, again, others have claimed they don’t,” she concludes.

“On average, the human brain contains about 100 billion neurons and many more neuroglia which serve to support and protect the neurons. Each neuron may be connected to up to 10,000 other neurons, passing signals to each other via as many as 1,000 trillion synapses” (Cornell University).

To philosopher John Searle, known, among other things, for his work in the philosophy of mind, the main problem with IIT is that: “[IIT] is saying that certain information just is consciousness, and because information is everywhere, consciousness is everywhere (…). [But] you can’t explain consciousness by saying it consists of information, because information exists only relative to consciousness.”

It’s too early to know whether IIT is correct or not, and to what extent.

For instance, in a 2022 paper, Dr. Tononi and co-authors respond to new critics. However, a new theory is now attracting attention, as its authors claim they have finally solved the hard problem of consciousness.

The new paper was published this year, in the journal Frontiers of Psychology, by Dr. Nir Lahav and Dr. Zachariah Neemeh, who recently finished his Ph.D. at the University of Memphis, in the United States, and is now teaching at Stanford. In their work, the researchers develop a conceptual and a mathematical argument according to which any attempt to explain consciousness that understands it as an absolute property independent of the observer is mistaken. We should, instead, view consciousness as relativistic.

As they explain in the paper,“Phenomenal consciousness is (…) just relativistic. In the frame of reference of the cognitive system, it will be observable (first-person perspective) and in other frame of reference it will not (third-person perspective). These two cognitive frames of reference are both correct, just as in the case of an observer that claims to be at rest while another will claim that the observer has constant velocity. Given that consciousness is a relativistic phenomenon, neither observer position can be privileged, as they both describe the same underlying reality.”

Who’s to say what the world’s true colors are? We perceive reality through our personal lenses. Photo: Sadie Hernandez.

Put more simply: the experience of consciousness from a first-person perspective (the observer), could look like brain activity and neuronal patterns from the perspective of another person observing the observer.

Therefore, if two people could occupy the same position in spacetime with the same brain activity, they would share the same experience of consciousness.

The relativistic theory of consciousness could allow us to determine which were the first organisms in which consciousness evolved and make it possible to determine the level of consciousness of many life forms, such as plants.

A 2022 paper on plant consciousness, by Dr. Miguel Segundo-Ortin, from Utrecht University in The Netherlands, and Dr. Paco Calvo, from the Universidad de Murcia in Spain, proposed that “we should not exclude a priori the possibility that plants have evolved their own phenomenal experience of the world.”

To Dr. Roger Penrose, who won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for proposing essential mathematical tools to describe black holes, consciousness must be beyond computational physics, and the fact that it exists “is not an accident”.

Dr. Penrose, together with Dr. Stuart Hameroff, posited a theory that consciousness arises from quantum effects in the human brain. The main locus of consciousness would not be the synapses between neurons, but what they call microtubules – tiny tubes made of protein that are found inside animal cells, including neurons. As Dr. Hossenfelder explains the theory, “In the brain, these microtubules can enter coherent quantum states which collapse every once in a while, and consciousness is created in that collapse. Most physicists, me included, are not terribly excited about this idea because it’s generally hard to create coherent quantum states of very large molecules, and it doesn’t help if you put these molecules into a warm and wiggly environment, like the human brain.”

If such quantum states were possible, given the current state of our civilization, what would it mean to find out that all the animals and plants are conscious, and discover all the possible different degrees of consciousness they could have?

The research of Dr. Lahav and Dr. Neemeh points to the exclusivity of experiencing consciousness. As we take advantage from our own unique position in spacetime, we can observe, or perceive, our consciousness from the first-person perspective. So, how does it feel? Could there be anything beyond information?