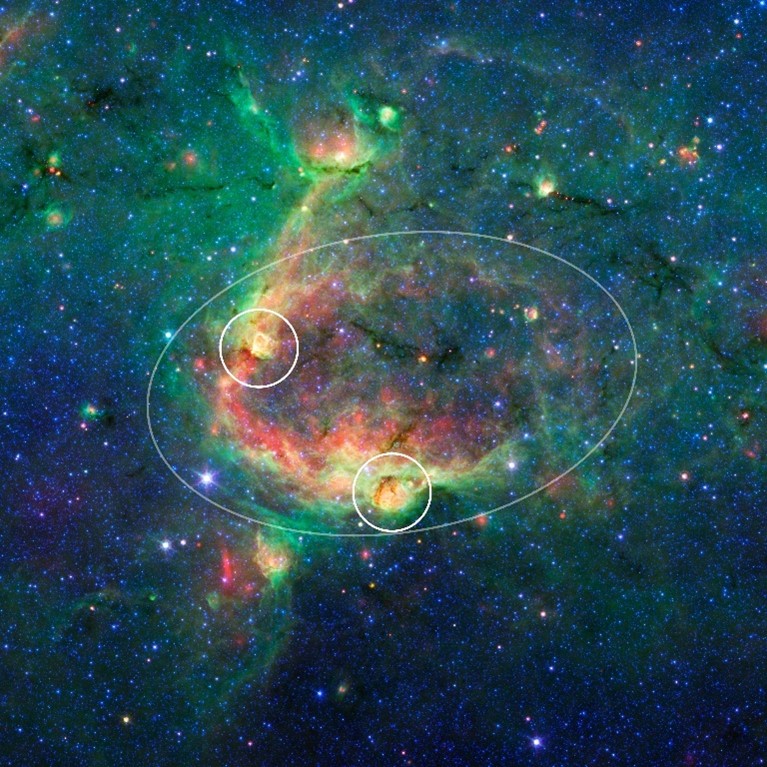

NASA/JPL image from the Zooniverse’s The Milky Way Project showing a hierarchical bubble structure. Image: Wikipedia.

Have you ever imagined making new scientific discoveries about the cosmos?

How about helping scientists track climate change effects in natural settings all over the world? Or maybe you’d be more interested in counting butterflies, monitoring water quality, or observing different plant life cycles?

Important scientific discoveries are often enabled by citizens who volunteer to help scientists, from the comfort of their homes. Citizen science is not something new but has become more robust and popular as technology advances and the world becomes more interconnected. That’s how a mysterious purple light in the sky ended up being named Steve.

Contrary to what many might believe, you do not have to hold specialized degrees to make important scientific contributions, and with the help of technology citizens are now less restricted to a passive role at the end of a one-way flow of scientific knowledge. Citizen science, also known as community, crowd, or civic science, is defined as scientific research conducted, in whole or in part, by non-professional scientists. It’s one important form of a collaborative construction of knowledge that allows many advancements in science while increasing the public’s understanding of scientific subjects and methods.

STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) and the Milky Way at Childs Lake, Manitoba, Canada. The picture is a composite of 11 images stitched together. Image: Krista Trinder.

The purple light known as STEVE, for instance, is the consequence of a citizen science project led by Dr. Elizabeth MacDonald and funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation’s project called Aurorasaurus, which tracks auroras through user-submitted reports and tweets. Steve was the name chosen by the citizens involved in the project for the thin purple ribbons of light no one could explain and that differed from normal auroras, which are light patterns in the sky caused by the interactions between charged particles from the Sun and the Earth’s magnetic field. The findings were published in a 2018 paper, and, thanks to the project, we now have a better understanding of a rare phenomenon and the Earth’s magnetic field.

The many discoveries of citizen science

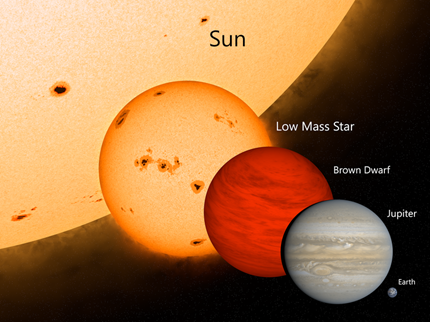

Examples of citizen-led discoveries abound, and a recent breakthrough in space exploration powered by citizen scientists could help astronomers better understand the dividing line that differentiates gas giant planets like Jupiter from stars. In 2022, the NASA public project called Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 led to the discovery of 34 new binary-star systems in which low-mass stars partner up with a so-called “failed star” or brown dwarf.

Size comparison of stars and planets. From left to right: The Sun, a red dwarf, a brown dwarf, Jupiter and Earth. Image: Planetkid32

“Brown dwarfs are small, intrinsically dim, and emit largely in infrared light […] All of these factors combine to make them both difficult to detect and easy to miss. [However], the large sky area and excellent sensitivity at red wavelengths provided by the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab) Source Catalog were key in enabling these new discoveries. […] It’s remarkable that modern data archives are so powerful that they can enable professional astronomers – and even enthusiastic amateurs – to make major discoveries, without ever needing to go to a telescope”, says Dr. Aaron Meisner, NOIRLab astronomer and co-founder of Backyard Worlds.

Breakthroughs powered by citizen science projects are found in many fields and countries. The Science with and for Society (SwafS) initiative of the European Commission focuses on enriching research and reinforcing public trust in science and innovation in the battle against climate change. Their goal is to promote a more participatory, inclusive, citizen-involved science, and many of their citizen science projects, whose focus is on climate change, have already contributed to the EU Green Deal objectives.

The monarch butterfly is a milkweed butterfly in the family Nymphalidae. It may be the most familiar North American butterfly and is considered an iconic pollinator species. Photo: Bernard Spragg

Interested in joining the movement? You have many options.

If you’re interested in becoming a citizen scientist, there are many options to choose from on the internet. For instance, if you live in the US, Canada, or Mexico you could join the Butterfly Census and participate in a one-day butterfly count for the North American Butterfly Association. Or you could use a test kit to sample local bodies of water for water quality data and share the results with Earth Echo International, an organization whose mission is to protect and restore our planet’s oceans. Another option could be observing plant life cycles for the Bud Burst Project, to gather environmental and climate change information in your local area by observing the life cycles of trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses for their first leafing, first flower, and first fruit ripening. But if you dream of having cosmic objects officially named after you, maybe you could volunteer for the NASA Stardust@home Project, and search images for interstellar dust impacts.

NASA is famous for having many citizen science projects – and they have helped to make thousands of important scientific discoveries. On their website, the organization makes clear that volunteers from any part of the world can join with just a cellphone or laptop. The Zooniverse is a group of citizen science projects operated by the Citizen Science Alliance that is home to some of the largest, most popular and most successful citizen science projects. Among them, two have been especially fruitful. One of them is the Galaxy Zoo, a crowdsourced astronomy project in which volunteers assist in the classification of large numbers of galaxies. The “Gems of the Galaxy Zoo’s” databases can be found here. Another initiative is the Milky Way Project, whose main goal is to identify stellar-wind bubbles in the Milk Way that scientists believe to be the result of young, massive stars whose light causes shocks in interstellar gas.

All these projects help spread the understanding that scientific knowledge is not discovered solely by scientists. This is a common theme behind these and other initiatives, such as the U.S. government’s Citizenscience.gov, which lists projects validated by federal employees, and the EU-citizen Science, a platform for citizen scientists to share knowledge, tools, training, and resources that aims to become the European citizen science reference point.

You can find many more citizen science projects in this National Geographic article. Who knows, maybe there is some cosmic dust out there waiting for your name to be attached to it!