Image by Satheesh Sankaran, on Pixabay.

By James Myers

As the popularity of physical currencies in the form of banknotes and coins continues to fade, will public and private digital currencies provide a reliable store of value for the economy of the future, or will they add to uncertainty?

The answer may hinge on whether governments can retain trust in their economic stewardship and foresight, since money has no intrinsic value and the usefulness of any currency is based on the faith that buyers and sellers place in it as a medium of exchange. The rise of private digital currencies – most notably cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum – can be read as a signal of decreased trust in traditional national currencies, but part of their increased circulation can be attributed to their utility for criminal payments.

The answer may also depend on the reliability of the technologies underpinning existing and planned digital currency offerings by national central banks, and blockchain technology that has enabled the global rise of cryptocurrencies.

A blockchain is a system in which a record of transactions, especially those made in a cryptocurrency, is maintained across computers that are linked in a peer-to-peer network.

Adding fuel to the increased use of cryptocurrencies as a store of value are national currencies and exchange rates that are becoming increasingly volatile in the face of geopolitical tensions, the rise of authoritarianism, and war in Ukraine and elsewhere. Adding further pressure to the value of money are global economic risks stemming from rapidly increasing government debts, inflation, the costs of environmental damage, and the rise of AI that continues to disrupt global job markets.

Currencies of smaller and less politically stable countries are especially at risk, most recently illustrated by the $20 billion credit provided to the Argentine central bank by the U.S. to forestall economic collapse. The largest economies are, however, not immune from currency devaluation.

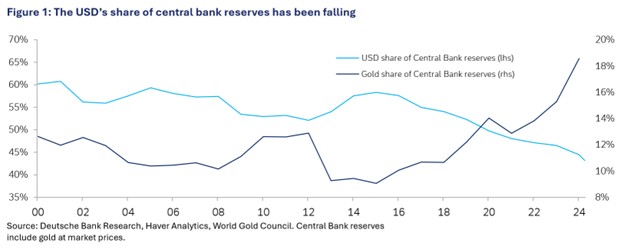

The rapidly decreasing share of the U.S. dollar in global central bank reserves is illustrated in this chart from the Deutsche Bank Research Institute’s September 2025 report Bitcoin vs. Gold: The Future of Central Bank Reserves by 2030.

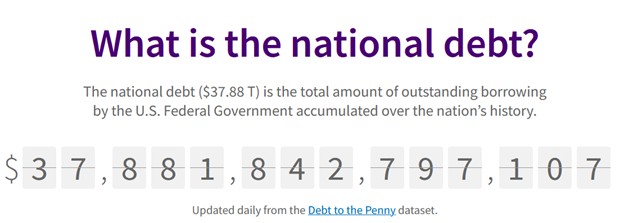

The rapid decrease in the proportion of U.S. dollars held in reserve by global central banks, trending down from 60% to 43% since the turn of the 21st century, highlights a marked shift from the global economic order established by the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. International currency stability was established near the end of the Second World War when 44 countries agreed at Bretton Woods to peg their currency values to the U.S. dollar and the U.S. agreed to peg its currency to the value of gold. Economic pressures forced the U.S. to abandon the gold standard in 1971, and in the 54 years since then the U.S. government has accumulated greater debt in all but 4 years. The U.S. federal debt now stands at nearly $38 trillion, an amount that could never conceivably be repaid and is sustained by global faith in the U.S. government’s ability to continue making interest payments.

Daily tracking of the U.S. government’s debt, as at October 4, 2025, from the Department of the Treasury. Of the nearly $38 trillion total, $1.973 trillion was added in the latest fiscal year ended September 30, 2025.

The U.S. dollar’s 8-decade reign as the world’s dominant central bank reserve currency has ensured a global demand for the currency, providing the U.S. government with a ready source of credit at lower interest rates than other countries are required to provide. With the shrinking appeal of the U.S. dollar in global central bank reserves, political polarization, and repeated U.S. government shutdowns over funding disagreements, other stores of value – including the Euro and cryptocurrencies – are gaining in popularity.

Part of the appeal of cryptocurrencies is their limited supply and verifiability on distributed ledgers enabled by blockchain technology.

Unlike the debt-driven increase in the supply of U.S. dollars, the number of Bitcoins, which are generated (“mined”) by computer algorithms, is capped at 21 million and the verifiability of its limited supply is enabled by blockchain technology. Some investors perceive the scarcity of cryptocurrency units as an important factor in their ability to act as a more reliable store of value than national currencies, which can suffer devaluation from political events, inflation, and the burden of debt.

The impetus for the issuance of Bitcoins was the global financial crisis of 2008 that was triggered by a loss of faith in the rapidly inflating value of assets held by financial institutions as collateral for loans. First proposed in 1982, the applicability of blockchains to currency transactions was advanced in 2008 by an unknown individual or group known by the name Satoshi Nakamoto. A blockchain consists of a sequence of digital records, called blocks, which are continuously added (or chained) to previous blocks. Each added block contains information about the previous block, so that the data in any block cannot be changed retroactively without altering all subsequent blocks. Blockchains enable a widespread and globally verifiable record of cryptocurrency transactions.

A distributed ledger is a digital record of the amounts and sequential order of exchanges between cryptocurrency holders. The ledger is synchronized across many systems, institutions, and countries so that its widespread agreement among numerous independent sources is evidence of accuracy and reliability. Unlike the databases of individual banks and governments, a distributed ledger does not rely on any one central administrator and therefore resists single points of failure.

The appeal of cryptocurrencies is, however, significantly diminished by their exceedingly limited acceptance as a method of payment.

Only two countries, Nicaragua and the Central African Republic, have given Bitcoin status as legal tender, although at the end of 2024 Nicaragua announced that businesses would no longer be required to accept Bitcoin as payment but could do so voluntarily. In the world’s developed economies, cryptocurrencies are scarcely accepted as a form of payment for retail transactions.

Although cryptocurrencies are seldom used for transactions in the U.S. and U.K., both countries have accumulated significant Bitcoin holdings mainly by seizures of cryptocurrency received as proceeds of crime. Regardless of Bitcoin’s infrequent commercial use, the U.S. government recently announced its intention to accumulate a national cryptocurrency reserve, which has contributed to increased values. Moreover, the introduction of a Bitcoin-denominated exchange-traded fund in 2024 has given retail investors an ability to participate in Bitcoin without direct ownership of the digital asset, further adding to value. The Deutsche Bank Research Institute concludes that within the next 5 years, Bitcoin might become a regular component of central bank currency reserves if its volatility, liquidity, strategic value, and trust continue to improve.

September 30, 2025 BBC headline.

While there may be a future for cryptocurrencies as part of the conventional economic structure, in the meantime they are especially appealing to criminals because the parties to cryptocurrency transactions are not recorded in distributed ledgers.

As a result, Bitcoin has become a favoured method of payment for thieves, extortionists, and scammers, since cryptocurrency exchanges are not regulated and monitored to the same degree as banks. Criminals commonly demand payment in cryptocurrencies for a range of crimes including ransomware, cyberattacks, and online relationship scams. Cryptocurrencies are also used to launder proceeds of crime. In September, a Chinese national was convicted by a U.K. court for illegally acquiring a staggering $6.7 billion in cryptocurrency purchased with funds from investment scams perpetrated against 128,000 victims between 2014 and 2017.

The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation’s (Europol) Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2024 notes that “Financial crimes, mainly investment fraud and money laundering, remains the area in which cryptocurrencies are most often encountered. Factors such as the increase in value of certain cryptocurrencies and growing media attention around crypto investments are also contributing to the steady surge in investment fraud cases.”

Cryptocurrencies do not provide stable values.

At the end of September, according to daily tracking by Forbes, the global value of 14,745 different cryptocurrencies stood at $4.1 trillion. Over half of the total value was held in Bitcoin, the most popular cryptocurrency, with each unit or “coin” trading for over $114,000. Some sources peg the total global money supply at approximately $150 trillion, using the broad M3 definition that includes physical currency, bank deposits, and liquid assets, and therefore cryptocurrencies represent somewhere around 2% of total value.

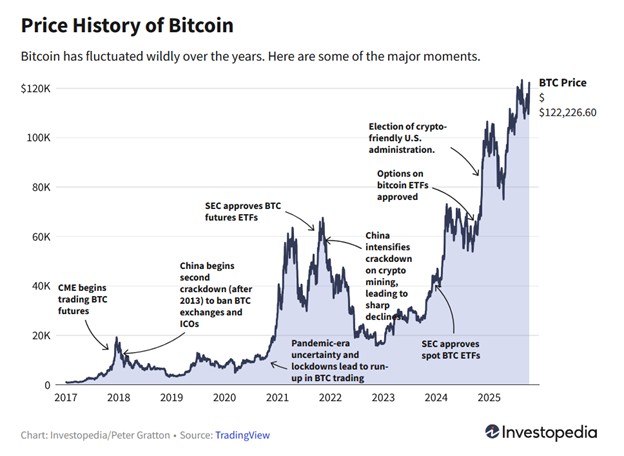

Graph of historical Bitcoin value fluctuations, noting significant drivers, from Investorpedia .

Over time, compared to national currencies (sometimes called “fiat” currencies) the trading values of cryptocurrencies are far from stable.

For instance, in the last week of September, Bitcoin’s value fluctuated by more than 4% with reference to the U.S. dollar, from a low of $109,000 to a high of $114,000, whereas during the same time the difference in value between the U.S. dollar and the Euro varied by only 0.2%.

In the past year, the price of a Bitcoin has nearly doubled, creating a windfall for those who held Bitcoins throughout the period while short-term speculators who sold Bitcoins in price dips during the year recorded significant losses.

Given the continued volatility of cryptocurrencies, stablecoins are gaining in popularity. Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies, but their value is pegged to a relatively stable asset like the U.S. dollar or a tradeable commodity. The American Banking Journal reports that in May 2025 the total volume of stablecoins pegged to the U.S. dollar amounted to $236 billion. Concern is mounting that increased flows of money from bank accounts into stablecoins will reduce the amount of loans that banks can issue, with negative economic consequences from reduced credit availability and higher interest rates.

Europol notes that proceeds of crime received in cryptocurrencies are increasingly being laundered by purchasing stablecoins, which is a concern both for law enforcement and currency regulators.

July 18, 2025 statement on the White House website, on the signing of the GENIUS Act.

In the U.S., stablecoins came under regulatory control in July with the enactment of the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act which requires stablecoin issuers to back the coins fully with cash or short-term U.S. treasury bills, to submit to audits, and to abide by anti-money-laundering laws. While the GENIUS Act prohibits payment of interest on stablecoin holdings, with the intention of making them equivalent to digital cash, the rule is being circumvented by issuers that are offering annual “rewards” equivalent in value to interest for holding stablecoins.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Baily recently stated that stablecoins achieving widespread acceptance in the U.K. should require depositor protection. Unlike bank deposits, which are typically insured to specific limits by national governments, there is currently no depositor protection for cryptocurrency holdings.

With stablecoins vying as a reliable alternative to national currencies, central banks around the world are considering issuing digital currencies.

Three countries have already done so. Traditionally, central banks like the Bank of Canada, Bank of England, Bank of France, and the U.S. Federal Reserve, issue currency in the form of physical coins and paper and they regulate the flow of physical and digital money by overseeing commercial banks and setting interest rates for commercial and interbank loans. The Bank for International Settlements reports that nearly all central banks are now preparing for the potential of issuing digital currencies exchangeable for physical cash, with three central banks having already taken the digital leap.

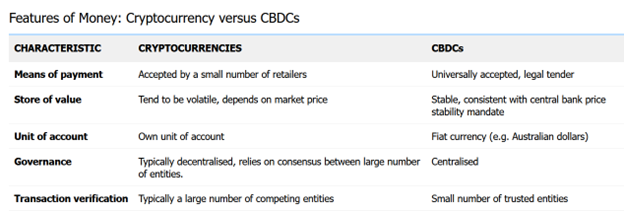

Comparison of cryptocurrency and CBDC features from the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are now available for retail transactions in Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Nigeria.

Other nations are working to develop technologies and processes in the event that CBDCs become commonplace globally. In the meantime, Residents of Jamaica, for example, can now make retail payments at stores and exchange money using either the paper form of Jamaican dollars held in physical wallets, or they can use the digital form of Jamaican dollars held in a virtual wallet that’s guaranteed by the central Bank of Jamaica and available through commercial banks and authorized payment providers. At any time, holders of virtual wallets can convert digital money to paper money, or paper money to digital.

Although interest isn’t earned on Jamaican dollars held in a virtual wallet, by eliminating commercial banks as payment intermediaries the advantages of CBDCs include zero transaction costs for consumers and reduced costs for merchants that now pay often 2% or more for transactions made by credit card. Further advantages include the ability to transact remotely whereas payments in physical cash require both parties to be in the same place, and obtaining a CBDC wallet is easier than opening a bank account which is a significant barrier for economically marginalized people.

CBDCs are not, however, without risk. The Bank of Canada notes that in the event of a banking crisis, “A central bank digital currency would make it easier and faster to transfer money out of commercial banks. So these system-wide runs could, in theory, become quicker and more frequent. We could end up in a situation where a central bank digital currency, instead of making the financial system more stable, makes it less so. Thankfully, runs on the entire banking system are extremely rare in modern times. In fact, Canada has never had one.”

From 2020-2023, the Bank of Canada conducted a stakeholder survey on digital currency and found that a significant concern surrounding the introduction of a CBDC was transaction privacy. “Respondents to the public questionnaire overwhelmingly valued the privacy and anonymity that bank notes provide and believed the Bank should not collect or have access to Canadians’ personal and spending information. Many of these respondents did not trust the Bank and other institutions to protect or respect their privacy and were concerned that privacy laws—such as the federal Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act—do not offer sufficient protections.”

The Bank of Canada also found that financial institutions were uncertain of the potential consequences from the introduction of a digital currency.

In an increasingly digital world, what is the future of money?

While the demise of transactions conducted by banknotes and coins continues, driven by the convenience of electronic payments by credit or debit especially for online purchases, there appears to be little desire for a completely cashless economy.

A 2023 survey by Payments Canada, a public purpose organization that owns and operates Canada’s payment systems, shows that while the volume of cash payments decreased by 59% in the 6 years from 2017-2022, over half of respondents indicated no desire to go completely cashless. “This is primarily due to cash being seen as a reliable, widely accepted, safe and secure payment option that Canadians do not want to live without,” the study notes. The anonymity, security, and ease of budgeting and control with cash transactions were significant factors weighing against a cashless economy.

The combination of a desire to retain a cash payment option and the ease of electronic payments may help to drive the adoption of central bank digital currencies. While cryptocurrencies are gaining in popularity with investors and may eventually become part of central banks’ reserve assets, their expansion is constrained by their criminal association and the scarcity of vendors that accept them as a stable form of payment.

In whatever ways money adapts to an increasingly digital world, the paramount objectives of the public will continue to be privacy and security of transactions. Although security is also a top concern for regulators, conflicting goals around privacy are emerging as a challenge for digital currency regulation when the use of cryptocurrencies for criminal activity continues to increase.