Fear and curiosity about the unknown have always motivated inquiry. Increasing the reliability of scientific methods and procedures allows us to better distinguish myth from reality. Image: Gerd Altmann, on Pixabay.

By Mariana Meneses

Have you ever had a premonition, a dream that seemed to foreshadow an event, or a sudden hunch that proved uncannily accurate? Though often brushed aside as coincidence, paranormal experiences like these have intrigued researchers in parapsychology.

This year, between July 15 and 18, the city of Freiburg, Germany, hosted the 67th Annual Convention of the Parapsychological Association. The event brought together studies spanning extrasensory perception (ESP), psychokinesis, near-death experiences, and the role of consciousness in shaping reality. The full collection of abstracts of the papers presented at the convention is available in a publicly shared PDF, offering a window into how this controversial field continues to test the boundaries of science and human experience.

“The abnormal is to be investigated; but naturally not because it is abnormal, but because it opens our view for understanding the essence of the normal.” – Hans Driesch. Parapsychology Convention in Freiburg in 1968..

In the chapter “The History of Parapsychology,” in the book “Probing Parapsychology: Essays on a Controversial Science,” edited by Grant R. Shafer (2023), the author V.G. Miller explains that parapsychology explores phenomena that appear to fall outside ordinary sensory or physical processes, grouped under the umbrella term “psi.” Researchers in parapsychology often investigate phenomena such as extrasensory perception (ESP), psychokinesis (PK), out-of-body experiences (OBEs), and near-death experiences (NDEs).

ESP refers to knowledge gained without the senses, including telepathy (mind-to-mind communication), clairvoyance (perceiving objects or events without mediation), precognition (knowledge of the future), and retrocognition (knowledge of the past, such as in past-life regressions). By contrast, PK refers to the alleged ability to influence objects or events without physical action, ranging from macro-PK, like claims of bending spoons with one’s mind, to micro-PK, detectable only statistically in labs. In OBEs, consciousness seems to leave the body, and in NDEs, people who were clinically dead report visions of tunnels, lights, or encounters with deceased figures before being revived.

A striking feature of the 2025 convention was the embrace of new technologies to test and systematize research on psi, this elusive domain of human experience that lies between psychology and physics, now being explored through machine learning, neuroimaging, and other data-driven approaches.

Several papers explored the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate labour-intensive steps in ESP research, such as designing target pools and judging free-response descriptions, with the aim of reducing human bias and improving replicability. Others integrated advanced neuroscience tools, including EEG, fNIRS, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), to probe whether modulating brain activity could enhance or suppress psi-related performance. Digital platforms were also highlighted, with studies using online remote viewing trials and large-scale open databases to ensure transparency, preregistration, and collaborative replication.

Together, these initiatives suggest that parapsychology is attempting to reinvent itself and meet the standards of mainstream experimental psychology.

The complexities of the human experience are yet to be fully understood by humans. Image: DeltaWorks, on Pixabay.

A more recent line of inquiry in parapsychology uses advanced technologies to explore parapsychological experiences in controlled settings.

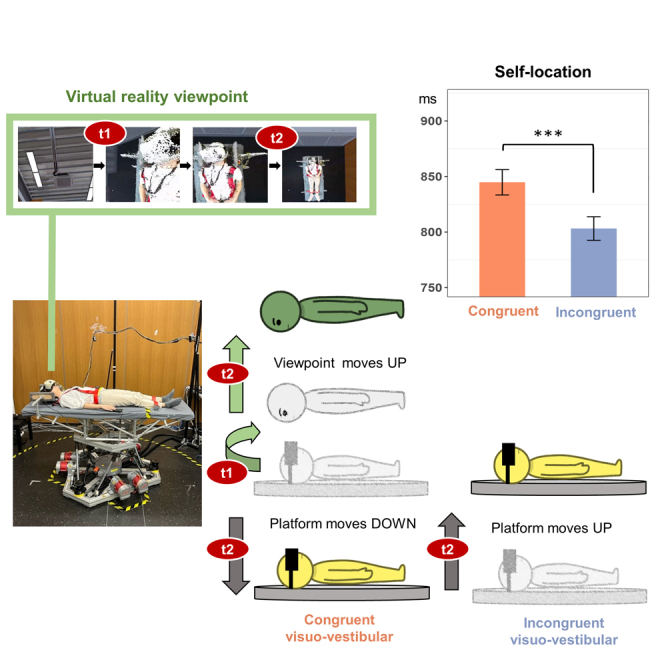

Aiming to experimentally reproduce out-of-body states in controlled settings, a 2023 study published in iScience by Hsin-Ping Wu and colleagues, from the Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, in Switzerland, used mixed reality combined with a motion platform to manipulate how visual and vestibular signals are integrated in healthy participants. In other words, the researchers wanted to alter how the brain merges what the eyes see (visual input) with what the inner ear senses about balance and motion (vestibular input).

By aligning visual and bodily motion cues in a self-centred frame of reference, the researchers were able to induce OBE-like illusions, including feelings of disembodiment, lightness, and perceiving the self from an elevated perspective. They further found that the strength of the illusion depended on individual differences in visual field dependency—the extent to which a person relies on visual cues rather than internal bodily signals (such as balance and motion sensed by the inner ear) to judge spatial orientation—measured with the classic Rod and Frame Test. In the test, participants adjust a rod to what they perceive as vertical inside a tilted frame.

These results suggest that OBEs may arise from disruptions or recalibrations in how the brain integrates visual and vestibular information, linking the phenomenon to mechanisms of bodily self-location. The work also reflects a growing interest in using immersive technologies not only to investigate altered states of consciousness but also to patent and develop systems designed to reliably induce them.

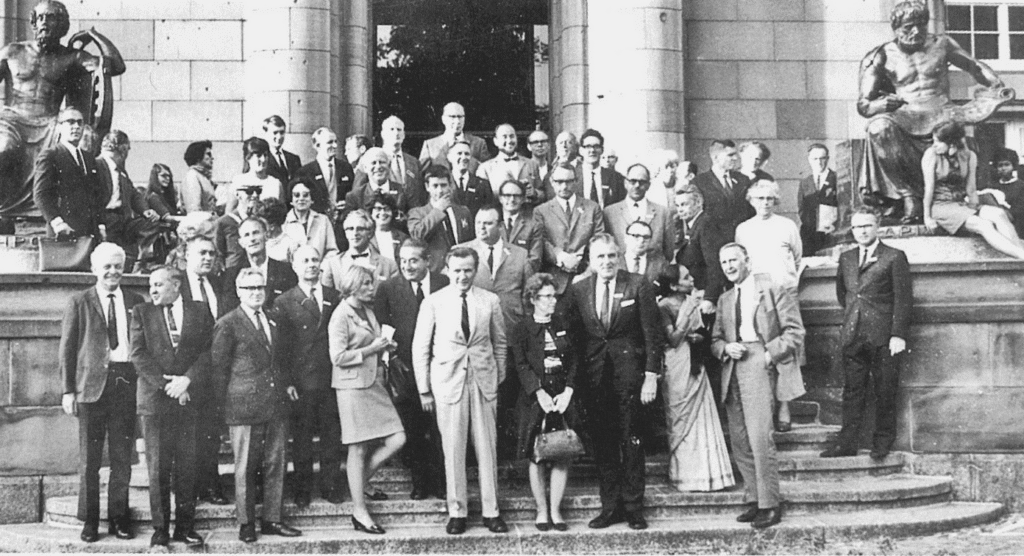

“Out-of-body experiences (OBEs) are defined as experiences in which a person seems to be awake and sees his body and the world from a location outside his physical body. More precisely, they can be defined by the presence of the following three phenomenological characteristics: (i) disembodiment (location of the self outside one’s body); (ii) the impression of seeing the world from an elevated and distanced visuo-spatial perspective (extracorporeal, but egocentric, visuo-spatial perspective); and (iii) the impression of seeing one’s own body (autoscopy) from this perspective. OBEs have fascinated mankind from time immemorial and are abundant in folklore, mythology, and spiritual experiences of most ancient and modern societies.” Bünning and Blanke, 2005.

A master’s dissertation by Sophia Kim Bertoni at the University of Coimbra (2024), titled Outside the Body, Inside the Scanner, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to visualize brain activity during a hypnotically induced out-of-body experience (OBE).

Unlike most previous neuroimaging studies, which relied on visual or tactile illusions to simulate OBEs, Bertoni’s pilot study focused on hypnosis as the induction method. This approach aimed to capture neural patterns during an OBE more directly, particularly in the temporo-parietal junction, a region associated with the brain’s embodiment mechanisms.

Image from Outside the Body, Inside the Scanner, by Sofia Kim Bertoni.

In one of two participants, the protocol successfully triggered an OBE, confirmed not only by subjective reports but also by distinct patterns of neural activation that differed from both control conditions and simple hypnotic induction. Though preliminary, the study demonstrates how modern imaging techniques can provide measurable correlations of phenomena once confined to anecdote or speculation, offering a potential bridge between subjective reports of altered states and empirical neuroscience.

Another technological development comes from the use of artificial intelligence to streamline ESP research.

A proof-of-concept study by David J. Acunzo and Jeremy Ky at the University of Virginia (2024), Using Machine Learning Methods to Automatize Target Pool Design and Judging in Free-Response ESP Experiments (PDF here), addresses two of the most labour-intensive aspects of remote-viewing studies: building large image pools and judging participants’ free-response descriptions.

Traditionally, target pools must be carefully designed to avoid duplication and ensure variety, while judges evaluate how closely participants’ reports match targets versus decoys—steps prone to subjectivity and inconsistency. The authors propose applying machine learning and natural language processing tools to partially automate both processes: pruning and grouping digital images into target sets and generating descriptors to compare against participants’ responses.

While still in early stages, their method shows how computer vision models and automated judging could reduce human bias, standardize procedures, and improve replicability. They stress, however, that these tools must be carefully validated against human judges and real ESP data before widespread adoption. If successful, such approaches could make free-response ESP research far less resource-intensive while offering more consistent standards across studies.

The way we investigate any subject is key to the power of any conclusion drawn from research.

Paul Kurtz, in 1979. Image: Roberto Tenore.

In 1981, American philosopher, scientific skeptic, and secular humanist Paul Kurtz (1925-2012) wrote a chapter for the book “Paranormal Borderlands of Science: Best of Skeptical Inquirer,” edited by Kendrick Frazier (1942 – 2022).

The chapter written by Kurtz is titled “Is Parapsychology a Science?”. In it, the author discusses key issues in scientific characterization, beginning with the meaning of the term “paranormal.” Although the word literally means “what is ‘besides’ or ‘beyond’ the normal range of data or experience,” it is sometimes also used as a synonym for what is bizarre, mysterious, or unexpected—definitions that do little to ground it in science.

Kurtz emphasized that claims labelled as paranormal frequently contradict some of the most basic principles established by centuries of observation: that the future cannot affect the present, that the mind cannot alter the physical world without some form of energy, that we can only know another’s thoughts through their behaviour, that distant events cannot be perceived without signals or sensory input, and that spirits do not exist apart from physical bodies.

The author argues these assumptions should not be abandoned unless there is overwhelming evidence yet notes that parapsychologists contend that they have uncovered findings that challenge such principles. Whether these anomalies truly justify revising the foundations of science, Kurtz concludes, is a question only future empirical inquiry can settle.

“Many of those who are attracted to a paranormal universe express an antiscientific, even occult, approach. Others insist that their hypotheses have been “confirmed in the scientific laboratory.” All seem to agree that existing scientific systems of thought do not allow for the paranormal and that these systems must be supplemented or overturned. The chief obstacle to the acceptance of paranormal truths is usually said to be skeptical scientists who dogmatically resist unconventional explanations. The “scientific establishment,” we are told, is afraid to allow free inquiry because it would threaten its own position and bias. New Galileos are waiting in the wings, but again they are being suppressed by the establishment and labeled “pseudoscientific.” Yet it is said that by rejecting the paranormal, we are resisting a new paradigm of the universe (à la Thomas Kuhn) that will prevail in the future.” (Paul Kurtz, 1981)

Where is the dividing line between science and pseudoscience?

The label “pseudoscience” has been applied in many ways, and Kurtz warned that it should not be indiscriminately used against emerging fields that may hold some scientific promise. By definition, the term “pseudoscience” fits areas that fail to use rigorous experimental methods, lack coherent and testable theories, or claim positive results that collapse under impartial scrutiny.

Kurtz asked whether parapsychology should be considered a science or a pseudoscience. He notes that the field has been plagued by fraud and self-deception—from the Fox sisters’ fabricated séances to discredited precognition studies and controversial figures like Uri Geller–but also that many parapsychologists have sought to apply careful laboratory methods, as J.B. Rhine, founder of the Parapsychology Lab at Duke University, did.

The Fox Sisters: America’s First Paranormal Scandal | Forgotten History

The central problem, Kurtz argued, lies in the results: while some experiments report above-chance outcomes in telepathy, precognition, or psychokinesis, these effects rarely replicate consistently. Because the findings remain elusive and unpredictable, parapsychology has yet to provide the robust and replicable evidence needed to challenge the basic assumptions of science.

Moving from the 1980s to more contemporary literature, a comprehensive overview comes from David Groome and Ron Roberts in Parapsychology: The Science of Unusual Experience (2024), which situates paranormal research within a wider spectrum of unusual experiences.

Their introduction points out that while modern science provides persuasive models for phenomena ranging from climate change to quantum physics, many aspects of human experience remain unexplained, or only partially explained. These include not only classic parapsychological claims such as extrasensory perception, mediumship, hauntings, and near-death experiences, but also cultural practices like exorcism, astrology, and even religious miracles – domains where mechanisms are poorly understood and evidence is often weak or inconsistent.

Importantly, Groome and Roberts stress that belief in such phenomena is far from marginal: surveys show that large proportions of adults in the US, UK, and India endorse ideas like psychic powers, ghosts, reincarnation, or astrology. This persistence of belief makes scientific study worthwhile, not only to test the validity of the claims themselves but also to understand the psychological and social mechanisms that sustain them.

Image of a séance: Freepik .

Groome and Roberts highlight two key contributions of parapsychological research.

First, because investigating alleged paranormal effects requires controlling for extremely subtle cues, such as unconscious experimenter feedback or inadvertent signals between participants, it exposes vulnerabilities in experimental design that are relevant across psychology. Second, the study of belief in the paranormal sheds light on how humans form and maintain convictions despite weak evidence, revealing the role of personality traits, cognitive styles, cultural background, and denial mechanisms in sustaining such faith.

The authors also confront the problem of replication and publication bias: high-profile claims, such as Daryl Bem’s experiments on precognition, often fail to replicate when tested independently, yet replication failures are far less likely to be published in mainstream journals. This “desk-drawer problem” skews the literature toward positive results, creating a distorted view of the evidence. Their conclusion is not that parapsychology provides proof of the paranormal, but that it serves as a testing ground for science itself, forcing researchers to refine methods, confront biases, and grapple with why extraordinary beliefs persist even when empirical support is lacking.

In “The History of Parapsychology”, Miller explains that parapsychological phenomena such as ESP, PK, OBEs, and NDEs are usually classified as either anecdotal or experimental.

Anecdotal accounts describe spontaneous experiences, like hunches, prophetic dreams, premonitions, visions, or sudden emotional surges, that seem to reveal hidden information about past, present, or future events, with the classic collection Phantasms of the Living (1886) (pdf) serving as an early compendium of such cases.

Experimental accounts, by contrast, involve controlled testing in laboratory settings, most notably J.B. Rhine’s card-guessing and dice-throwing studies at Duke University in the 1930s, later followed in the 1960s by experiments using electronic randomization and systematic recording of participants’ guesses.

In a more favorable light, experimental psychologist Douglas M. Stokes’s The Nature of Mind: Parapsychology and the Role of Consciousness in the Physical World (1997) suggests that modern physics itself opens space for parapsychological inquiry. If, at any given moment, an infinite number of possible futures exist, then consciousness may play an active role in selecting which of those futures becomes reality, implying that the mind could exert a fundamental influence on the unfolding of the cosmos.

Image: Freepik .

According to Stokes, western science portrays human beings as nothing more than temporary collections of atoms governed by physical laws, with no role for a soul or mind beyond the body, and death as the definitive end of existence. Yet some parapsychologists argue that unexplained phenomena, from dreams that seem to predict accidents to poltergeist outbreaks, hint at limits in this materialist view.

To explore such claims, researchers have turned to experiments on extrasensory perception and psychokinesis, though results remain contested amid skepticism, fraud, and methodological flaws. Theories proposed to explain these anomalies range from particles travelling backward in time to the interconnectedness suggested by quantum mechanics, even raising the possibility of a collective mind. The debate extends to questions of consciousness, the mind–body problem, and whether minds might survive bodily death, with evidence ranging from past-life memories to encounters with the dead.

“Skeptics can always claim that there are plenty of nervous women who periodically dream about their husbands dying in car crashes. Sooner or later, they argue, one of these husbands is bound to be taken out by a drunk driver or to drive his Porsche through a department store window. Thus, nothing more than coincidence may be involved in such cases. For this reason, parapsychologists have turned to experimental studies to prove the existence of such paranormal powers as ESP or psychokinesis (the power of mind over matter). In such experiments, subjects may guess the order of the cards in a shuffled deck that is hidden from their view. They may try to use their psychokinetic powers to influence the outcome of the roll of a pair of dice or to influence the motion of a group of balls cascading down a chute. Whether such experiments have succeeded in proving the existence of ESP and psychokinesis will not be an easy issue to resolve. We will be forced to look at science at its ugliest, from the prejudice of irrational skeptics to fraud and incompetence on the part of some (but by no means all) of the experimental workers in the field.” (Douglas M. Stokes, 1997).

A PhD thesis (PDF here) written by Abby Lauren Pooley at the University of Edinburgh in 2024 uses parapsychology as a case study to scrutinize the fragility of research practices in psychology, focusing on the psi Ganzfeld experiment—an attempt to test clairvoyance, telepathy, and precognition by placing participants in sensory deprivation and asking them to identify randomly chosen images or videos. The original Ganzfeld experiment is a psychological experiment that involves sensory deprivation to study hallucinations. However, when conducted with a “sender” who tries to communicate images to a “receiver” in a state of sensory deprivation, it becomes a psi Ganzfeld experiment.

In a typical setup, a “receiver” is placed under mild sensory deprivation, with ping-pong ball halves over the eyes, under red light, and listening to static noise in headphones, while a “sender” attempts to mentally transmit a randomly chosen image or video. After describing their impressions aloud for about 30 minutes, the receiver selects from several possible targets, with a 25% success rate expected by chance. Parapsychologists argue that above-chance hit rates suggest evidence for ESP, especially when participants possess traits like prior psi experiences, meditation practice, or creativity, while critics caution that such selective sampling introduces bias.

Since its introduction in the 1970s by Charles Honorton, who linked ESP to dream-like states, the Ganzfeld has become central to parapsychological research, evolving into digital “autoganzfeld” versions to improve randomization and experimenter blindness. Yet despite occasional reports of statistically significant results, independent replication has remained elusive, and many scientists continue to regard Ganzfeld findings as unverified and emblematic of pseudoscientific hallmarks.

Critics of the Ganzfeld experiment pointed to recurring methodological flaws that undermine its claims. Richard Wiseman, Professor of Public Understanding of Psychology at the University of Hertfordshire, and others have noted that not all studies were conducted in soundproof rooms, raising the possibility that experimenters could hear the target video and unconsciously cue the receiver, or that receivers themselves might overhear sounds.

The procedures for randomizing target options have also been questioned, since poorly controlled randomization can bias participants toward choosing the first option shown. Perhaps most fundamentally, critics challenge the assumption that any statistical deviation from chance is evidence of telepathy: such deviations may simply reflect rare coincidences or flaws in the experimental design, making it fallacious to treat them as proof of psi.

Richard Wiseman is a professor at the University of Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom. He is a fellow for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and a patron of Humanists UK. Wiseman is also the creator of the YouTube channels Quirkology and In59Seconds. Image: BDEngler

Common criticisms of the Ganzfeld experiments thus include persistent methodological weaknesses and the absence of independent replication.

In 1985, C. E. M. Hansel pointed to design flaws and sensory leakage in Carl Sargent’s studies, concluding that ESP was no closer to being established than a hundred years earlier. David Marks later showed that even in the autoganzfeld setup (digital “autoganzfeld” versions), soundproofing was inadequate, allowing for possible information leakage. Terence Hines argued in 2003 that any apparent effects vanished under tighter controls, making it most reasonable to conclude that no genuine psychic phenomena were involved.

Ray Hyman, in a 2007 review, stressed that psi is only negatively defined, treated as whatever cannot be explained by normal causes, and warned that such reasoning allows anomalies to be labelled as psi without independent verification. He suggested that inconsistent results are more likely due to ordinary errors than to revolutionary new abilities. Further critiques echo this skeptical stance: Scott O. Lilienfeld and colleagues wrote in 2011 that ESP has not been reliably demonstrated in more than 150 years of experiments, and Brian Dunning concluded in 2013 that the Ganzfeld technique had failed as evidence for psi.

The Ganzfeld research has also been marked by controversy, particularly surrounding the work of Carl Sargent in the late 1970s. When Susan Blackmore visited his Cambridge laboratory in 1979, she observed several irregularities during one of the sessions, including Sargent conducting randomization when he should not have, his direct involvement in nudging a subject’s choice, and an addition error that favoured the correct target. Although these issues were not formally published until 1987, they circulated widely among parapsychologists and fueled doubts about Sargent’s methods.

While Sargent and his colleagues dismissed the problems as random mistakes rather than fraud, he soon withdrew from parapsychology and allowed his membership in the Parapsychological Association to lapse after failing to share his data. Decades later, Blackmore was more direct, writing in Skeptical Inquirer (2018)that Sargent had “almost certainly cheated.” She also criticized psychologist Daryl Bem for continuing to cite Sargent’s and Charles Honorton’s research without disclosing the serious doubts surrounding them, arguing that such omissions mislead the public into believing there is solid scientific evidence for ESP in the Ganzfeld experiments when there is not.

A further perspective comes from the intersection of parapsychology and cyberpsychology, the study of human behavior in online environments.

In a 2024 article (not open access) titled Parapsychology and Cyberpsychology, Claire Murphy-Morgan and Callum E. Cooper highlight how digital technologies are reshaping both the conduct and the perception of parapsychological research. They note that the internet has long served as a vehicle for experiments, surveys, and dissemination of findings, but also exposes the field to challenges such as polarization, censorship, and fake information.

Drawing on Kirwan’s three pillars of cyberpsychology (i.e., how we interact with others, how we adapt technology to our needs, and how technology changes behavior), the authors argue that these frameworks are increasingly relevant to parapsychology, particularly in understanding how anomalous experiences are mediated and discussed online. Looking ahead, they suggest that emerging technologies like AI, virtual reality, and digital memorial platforms could open new avenues for studying phenomena such as post-mortem bonds with the deceased, while also raising pressing questions about how these technologies shape our perceptions of consciousness, identity, and the afterlife.

Recent research also underscores how easily bold claims can circulate without solid evidence.

For instance, Richard Wiseman and Caroline Watt (2025) examined popular social media assertions that the way people interpret ambiguous images, such as the Duck–Rabbit or the Younger–Older Woman, reveals personality traits or thinking styles. Their study found little empirical support for most of these ideas, showing how such notions often amount to what they call “psychological myths.”

“Optical illusion showing a duck (facing left) and a rabbit (facing right) at the same time.” Image: Fastfission~commonswiki

A related caution emerges in Diane Hennacy Powell’s review (2024) of Jeff Tarrant’s Becoming Psychic, where she critiques the author’s portrayal of himself as a hardened skeptic transformed by psi experiments. Powell notes that Tarrant’s long-standing fascination with the paranormal and his eagerness to experiment with techniques like Ganzfeld, crystals, and transcranial magnetic stimulation suggest that his narrative of scientific conversion is overstated.

In both cases, the takeaway is similar: whether circulating online or presented as personal testimony, claims about anomalous cognition often appear more compelling than the limited evidence behind them.

Image: Freepik .

Taken together, these threads point to a simple, demanding ethic: investigate the abnormal not to romanticize it, but to sharpen how we know the normal.

Parapsychology may act as a stress test for scientific practice, exposing how fragile findings become without preregistration, tight controls, and many independent replications – and how easily compelling stories outpace thin evidence.

The turn to sophisticated methods, from AI to brain stimulation and digital platforms, reflects a desire to meet mainstream scientific standards. The intellectually honest seem to have neither credulity nor contempt, but open-minded rigour, welcoming surprising results, insisting on methods others can reliably repeat, and being willing to update or abandon claims when stronger evidence (or lack of it) requires.

Have we made any errors? Are you an expert on this subject and want to contribute to future content?

Please email us, as we would love to learn more and correct any unintended publication errors. Our aim is to engage an ever-growing community of researchers with the goal of communicating—and reflecting—on scientific and technological developments worldwide, in plain language.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Everything Has a Beginning and End, Right? Physicist Says No, With Profound Consequences for Measuring Quantum Interactions

- Cleaning the Mirror: Increasing Concerns Over Data Quality, Distortion, and Decision-Making

- Not a Straight Line: What Ancient DNA Is Teaching Us About Migration, Contact, and Being Human

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies