The weather-forecasting supercomputer named “Dogwood” was installed by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in mid-2022. Image: General Dynamics Information Technology.

By James Myers

The remarkable capacity for artificial intelligence to connect weather patterns and their outcomes, by rapidly processing and correlating massive amounts of data, is giving us a clearer picture of the near future for Earth’s climate.

Although that picture is grim, showing the likelihood of passing a climate tipping point of no return within a few short years, machine learning and AI are adding significant strength to mathematical methods for weather prediction. The combination of increasingly powerful AI with mathematics lends new hope for developing technology that could help us avoid tipping the planet’s climate beyond the point of no return.

There is almost no time left for action. Restoring balance to the global ecosystem is crucial for the health and future livelihood of today’s children and generations to come, and for curbing the rapid escalation of financial losses that the havoc of extreme weather is already causing. In its Global Catastrophe Recap, Aon, which is the world’s second-largest insurance broker, estimated that insured losses from natural disasters worldwide for the first six months of 2025 amounted to $100 billion. The total is the second highest on record and more than double the average of $41 billion for the first six months of every other year so far this century. Nearly 75% of the global losses arose from four events in the U.S.: two large fires in tinder-dry California, and two severe storms.

“The term ‘tipping point’ commonly refers to a critical threshold at which a tiny perturbation can qualitatively alter the state or development of a system.” — Timothy M. Lenton and co-authors, Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system

The most commonly used method for forecasting is called numerical weather prediction (NWP), in which current weather data from satellites, ground-based readings, and other sources are fed into supercomputers that calculate future probabilities based on the interaction of many variables. Treating the atmosphere as a fluid that interacts with water bodies, land, and the biosphere, NWP applies mathematics of fluid motion from the Navier-Stokes equations to predict future outcomes.

The Navier-Stokes equations are partial differential equations that determine rates of change in dynamic systems with multiple variables, by identifying the point of balance in the momentum of fluid motion. Momentum is the product of the mass, speed, and direction of the system’s components, and locating the point of balance in a fluid flow like air is critical for measuring change and calculating future probabilities. Navier-Stokes equations are widely used for other purposes, ranging from the aerodynamic design of aircraft and cars to medical diagnostics for blood flow measurement.

Typically, an AI’s neural network structure processes weather data iteratively, repeatedly passing the inputs through multiple layers of mathematical operations, including the Navier-Stokes equations, to locate the patterns and key variables that drive weather systems. In a process called autoregression, predictions generated at each step of data processing are fed back into the processor as an input for the next prediction in the continuous refinement of probabilities. Autoregression is also used in training large language models like ChatGPT.

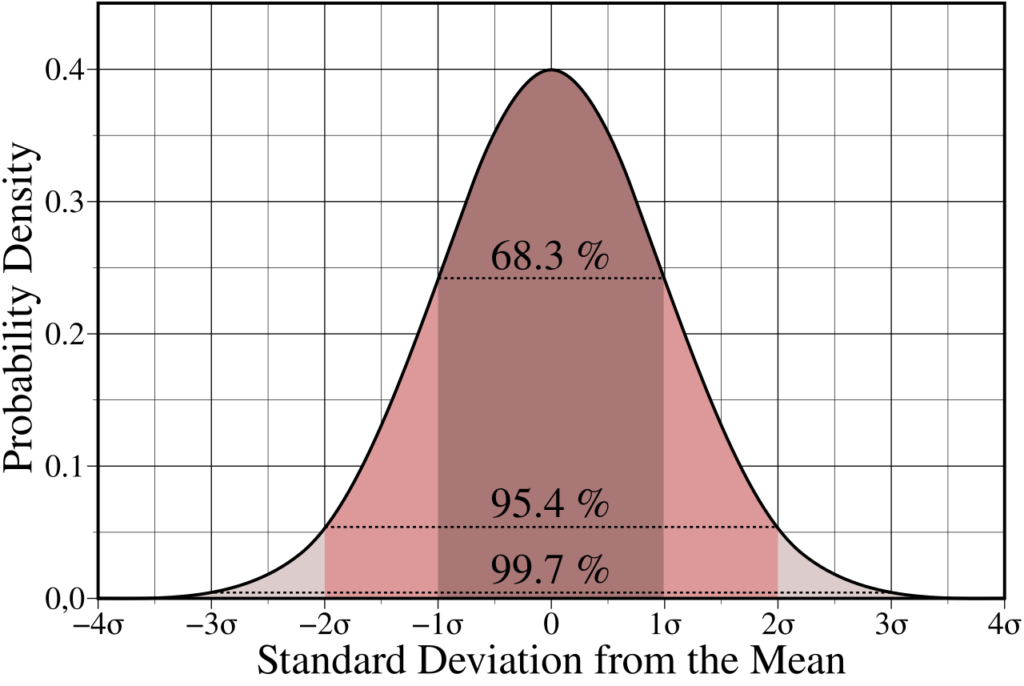

This graph illustrates the normal, or Gaussian, distribution for a particular probability calculation. Increasing the sample size produces an average probability shown at the peak of the graph. Image: Wikipedia .

Rapidly increasing interest in the use of AI for weather forecasting is evident from the trend in scientific papers published on the subject. One survey of the literature found less than 100 papers published in 2011, a number that exploded to about 2,200 papers in 2022 with the emergence of new and powerful AI capabilities. Interest is likely to increase further with the development of a new system that will enable many more professional and citizen scientists to generate weather predictions by reducing the heavy computational costs that have traditionally limited access to the science.

Called Aardvark Weather, the new system is expected to produce results comparable to traditional methods but at 10 times the speed, with a fraction of the data, and consuming 1,000 times less computing power. Aardvark Weather can be operated on a regular computer or laptop, and its open-source programming and ease of customization will allow small organizations, developing nations, and people in remote regions to generate local forecasts on a minimal budget.

Under development by Cambridge University and the Alan Turing Institute, Aardvark Weather was announced in a March 2025 paper entitled End-to-end data-driven weather prediction and published in Nature. A significant benefit of the new system is its ‘democratization’ of forecasting; as the developers note, “The simplicity of this system makes it easier to deploy and maintain for users already running NWP and also opens the potential for wider access to running bespoke forecasts in areas of the developing world where agencies often lack the resources and expertise to run conventional systems.”

This brief video, from the Alan Turing Institute, compares the accuracy of an Aardvark Weather windspeed forecast with what occurred (labelled as Ground Truth) in tropical cyclone Berguitta, which caused £100 million in damage in Mauritius and Réunion in 2018.

One of the paper’s authors, James Requeima, explained the computational advantage of Aardvark Weather. “Rather than the traditional, iterative process that relies on expensive numerical simulations, we train our model to map directly from sensor inputs to the weather variables we care about. We feed in raw observational data — from satellites, ships and weather stations — and the model learns to predict precipitation, atmospheric pressure, and other conditions directly. While training the initial model requires computational resources, once trained, it’s remarkably efficient.”

The rapid evolution of AI capabilities is shaping the future of weather forecasting.

AI is a key strategic element, for example, for the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Founded in 1975, the U.K.-based ECMWF produces numerical weather predictions for 35 member and cooperating states as well as the broader global community.

In 2025, the ECMWF initiated the latest version of its Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS), called AIFS ENS (pdf available). Earlier generations of machine learning applications for weather forecasting are less reliable because excessive averaging over many calculations results in improperly weighted probabilities, whereas AIFS ENS employs a more accurate method called Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS). CRPS can be trained to forecast at many different steps of data processing, requiring only one model evaluation for each step which significantly reduces the need for energy-intensive computational resources.

AIFS ENS has been trained on 38 years of weather data, from 1979 to 2017. As a result of its proficiency in handling variable factors lower in the atmosphere, comparisons of its predictions to an alternative widely used technology called IFS ENS show that, “forecast improvements reach up to 25% and that AIFS ENS has higher forecast skill for upper-air variables. The skill improvements result from reductions in both bias and random component forecast errors. Degradations, however, are seen for forecasts of conditions higher up in the atmosphere.”

Shown here in its final stages of construction, the Copernicus Programme’s Sentinel 6-A satellite was launched at the end of 2020 and is equipped with sensors dedicated to measuring changes in the height of sea surfaces around the globe. Image: Airbus Defence and Space/L. Engelhardt

Refining calculations and data processing methods is part of an approach to increasing forecast reliability that also includes obtaining more detailed weather observation data. The ECMWF is a member of the European Union’s Copernicus Programme, which combines Earth-monitoring data from satellites, aircraft, ocean platforms, and ground observation stations to provide free and high-quality environmental information to member nations and the public.

Together with many European national weather services and the European Union, the ECMWF is also a partner in a project called RODEO, whose mission is to create user interfaces and interconnect climate monitoring systems in order to expand access to key meteorological data for policymakers, businesses, and the public. RODEO has developed an interface called MeteoGate, which it describes as “a ‘One-Stop Shop’ for meteorological data and information in Europe.” The organization has also created open-access web services that provide real-time surface weather observations and has integrated the weather warning technologies of its partners to provide crucial public alerts that are accessible, reliable, and consistent.

RODEO has also facilitated the development of two publicly available example weather condition datasets for use in machine learning application development and validation of machine learning outputs.

While mathematical forecasts weigh probabilities, they cannot overcome uncertainties.

The challenge with mathematical models for climate interactions is the huge number of variable factors in climate change. An error or omission in the mathematical formulas and inputs for forecasting long-term climate conditions based on many data variables – such as temperature, ocean currents, population densities, windspeeds, and rainfall – risk multiplying over time into significant forecasting differences.

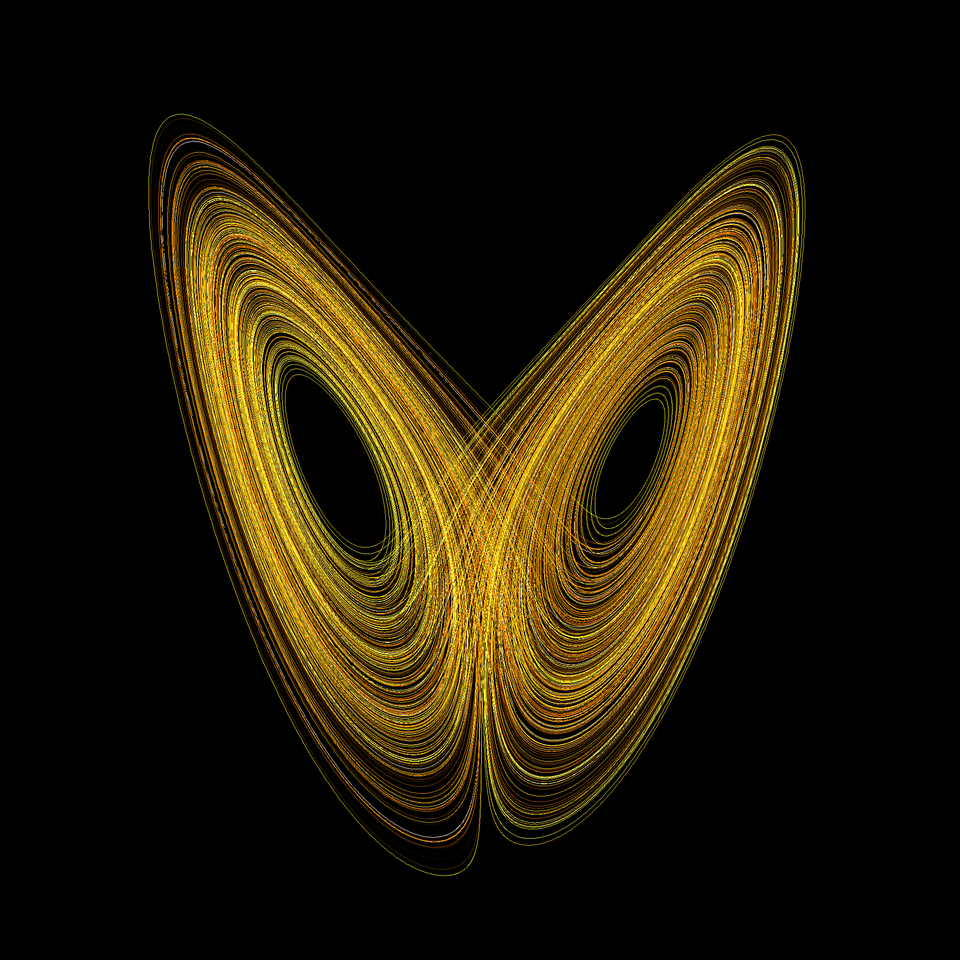

Complex weather patterns are highly dependent on initial conditions, and a small difference in measuring the conditions at the onset of a weather system can produce major variances in projections over time in a phenomenon known as the “butterfly effect.” The term was coined by mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz (1917-2008) to describe the consequences of a single event in time, such as one flap of a butterfly’s two wings, that seems completely forgettable and inconsequential when it happens. The butterfly effect occurs in the long run, when a disturbance as tiny as a bunch of air molecules tossing around an insect’s wings multiplies exponentially over time to the point that it shapes an entirely different future.

The Lorenz attractor is evident at the points of convergence in this graph showing the evolution of a dynamic system. The shape of the graph resembles the wings of a butterfly. Image: Wikipedia .

Lorenz developed the mathematical theory for weather and climate prediction based on dynamic systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions. The Lorenz method focuses on locating an attractor, which is a state to which a dynamic system like weather continuously returns in its evolution. The work of Lorenz is central to chaos theory in mathematics.

Chaos: “When the present determines the future but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.” – Edward Lorenz

The uncertainties of mathematical probabilities have been used by many as an excuse for inaction in preventing further damage to the environment, but the added power of AI is producing more accurate and longer-range forecasts that could give far less reason to doubt the urgency for immediate action. Although calculated probabilities inevitably involve uncertainty, mathematics has also reduced uncertainty because it has been fundamental to advancing the capabilities of AI. Mathematics is crucial for the development of neural networks that enable AI-generated weather forecasts and remains instrumental for expanding AI’s capabilities.

Caution is necessary, however, in communicating the results of mathematical predictions. Calculations that forecast events for specific dates and precise climate outcomes can be met with scepticism and risk public dismissal for being alarmist. One example is a controversial study released in 2023 that predicted with 95% confidence the collapse of a key global climate regulating system called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The tipping point for the AMOC will occur sometime before the year 2095, according to the study, and most likely in 2057. Co-authored by climate scientist Peter Ditlevsen and his sister Susanne Ditlevsen, who is a statistician, the study was published in Nature Communications.

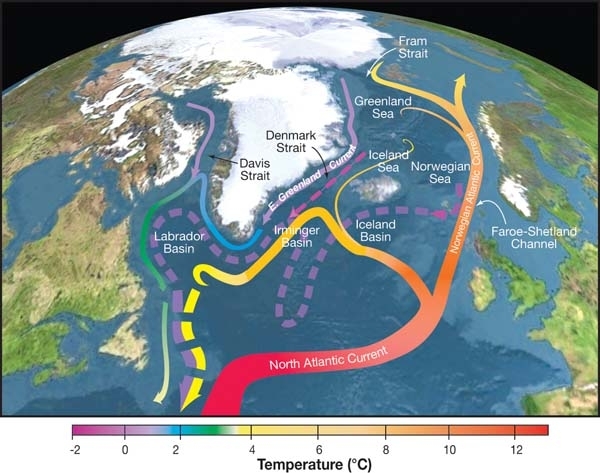

Under observation for many decades, the AMOC is a major Atlantic Ocean current that is driven by the concentration of saltwater near the equator where the sun’s heat causes significant evaporation of surface water. The warm, salty water flows north, eventually cooling, sinking, and turning back after carrying an estimated 25% of the total heat received in the northern hemisphere and moderating the climate of much of northwest Europe. There is much scientific evidence for a significant recent reduction in the amount of heat that the AMOC is delivering, and concerns are mounting that among the possible causes are the rapid melting of ice in Greenland and general ocean warming from increasing levels of potent greenhouse gases like methane.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation consists of surface currents (shown in solid curves) and deep currents (shown as dashed curves). Hotter currents are in red, and the shift to yellow indicates cooler currents. Image by R. Curry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution/Science/USGCRP, Wikipedia.

In forecasting the interaction of an incredible number of variables over long times, a mathematician’s selection of the determining factors weighs heavily on the outcome. For example, is the best measure for gauging the health of the AMOC provided by the surface temperature of water in an area off the southwest coast of Greenland called the Atlantic subpolar gyre, as the forecasters used? Errors in the weighting given to that factor, or the use of other potentially more relevant factors, could change the tipping point forecast by hundreds of years. There is also the challenge of correctly correlating data with a system as large as the AMOC, since it remains unknown whether it acts as a single unified system or instead as a combination of sub-systems, each with its own determining factors.

Prediction outcomes are also dependent on the particular mathematical methods employed to forecast climate outcomes. For example, in a 2024 article in Nature Communications entitled Real-world time-travel experiment shows ecosystem collapse due to anthropogenic climate change, Dr. Guandong Li, an environmental scientist at Tulane University, and co-authors used statistical analysis to conclude that “drowning of approximately 75% of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands is a plausible outcome by 2070.”

The researchers found linear trends in data correlating “13 years of unusually rapid, albeit likely temporary, sea-level rise” in the Gulf of Mexico to wetland conditions in the state of Louisiana. To extrapolate the trends into the future, they applied a statistical method called ordinary least squares regression, and tested the significance of the results using Monte Carlo simulations. The Monte Carlo testing method employs algorithms that provide numerical outcomes based on repeated random samples, which are used to identify patterns in the data and correlations among inputs.

The mathematical methods for assessing dynamic systems continue to evolve, with an added push from the recent focus on developing quantum sensors. As The Quantum Record reported last month in The Quantization of Warfare: The Technological Battlefield That Overpowers Both Sides in Human Combat, quantum sensing is particularly attractive for military powers because the technology will enable precision navigation and enemy targeting that’s far more accurate that methods now in use. By significantly reducing uncertainty in measuring the dynamics of motion, quantum sensing will also have a range of applications in physics, medicine, and other sciences.

The evolution of mathematics for quantum sensing includes a recent focus on developing statistical methods for measuring quasiprobabilities, which could also unlock new methods for forecasting the probabilities of weather patterns. A quasiprobability is the relationship between probabilities, and studying quasiprobabilities could provide new information to reduce prediction uncertainty.

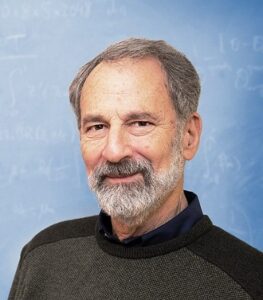

Princeton University mathematics professor Charles Fefferman provided the official problem definition for the Navier-Stokes equations for which the Clay Mathematics Institute is offering a $1 million prize. Image: Institute for Advanced Studies.

In addition, mathematicians continue to probe for exceptions in the Navier-Stokes equations that are key for numerical weather prediction. The Clay Mathematics Institute is offering a $1 million prize for proof that the equations are either incapable of illogically producing an infinitely large output (referred to as a “blowup”) or that they contain some illogic that will cause a blowup under certain conditions. Recently, a group of mathematicians has developed a machine learning process to hunt for Navier-Stokes blowups, in the course of which they identified a number of candidates for blowup scenarios.

The benefits of improved climate prediction technology and methods are clear.

Human responsibility for dangerous climate changes that have been clearly evident over recent decades is undeniable. Toxic industrial output, urbanization of the planet’s natural surface, overuse of natural resources, and the relentless accumulation of carbon pollution from 8 billion humans are already driving many species to extinction at an alarming rate. Like a human body that suffers repeated bouts of disease and injury, natural systems can reach a tipping point where they’re no longer self-sustaining and begin a rapid and irreversible decline.

The Earth has experienced sudden radical climate changes many times in its 4.5-billion-year history, but until now none have been human-caused.

For example, around 66 million years ago, the energy released by an asteroid strike near Chicxulub, Mexico boiled the planet’s water and charred its land, causing a mass extinction of most life on Earth and ending the age of the dinosaurs. Although the causes of the latest 100,000-year-long ice age, which ended around 12,000 years ago, are uncertain, many theorize that a major eruption of volcanic ash may have blocked the sun’s energy with the result that large parts of Earth’s land mass froze in sheets of ice.

The potential for natural disasters like these to disrupt life on Earth won’t go away, but AI and mathematics are giving us a fighting chance to prevent climate disasters of our own making.

Want to learn more? Here are some TQR articles we think you’ll enjoy:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Can Science Break Free from Paywalls? Technologies for Open Science Are Transforming Academic Publishing

- COP-30 in Belém: What Emerging Technologies Can and Can’t Deliver for Planetary Health

- The Science of the Paranormal: Could New Technologies Help Resolve Some of the Oldest Questions in Parapsychology?

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies

Have we made any errors? Please contact us at info@thequantumrecord.com so we can learn more and correct any unintended publication errors. Additionally, if you are an expert on this subject and would like to contribute to future content, please contact us. Our goal is to engage an ever-growing community of researchers to communicate—and reflect—on scientific and technological developments worldwide in plain language.