“Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.” — H. G. Wells (1898), The War of the Worlds

- The War of the Worlds (title page), 1927 Amazing Stories reprint, cover illustration by Frank R. Paul

- The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells, First Edition, 1898

By John Bamford

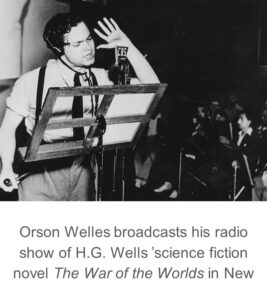

The War of the Worlds was one of the many novels and short stories by prolific author H.G. Wells. He was nominated four times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, with The War of the Worlds being a particular stand-out. Never being out of print, it generated multiple motion pictures, television series, radio broadcasts, recordings, comic book versions and other stories and spin-offs. One of the most memorable was Orson Welles’ radio adaptation of the The War of the Worlds on The Mercury Theatre on-air broadcast of Halloween 1938. Panic and newspaper headlines erupted, as did Welles’ fame.

“Invasion literature” is a category of writing that emerged between 1871 and World War I (1914-1918). It started with fears of a German invasion of England, which stoked western anxieties, which in turn prompted fears of potential invasions by other malevolent nations, and eventually other malevolent alien nations, which sparked literary imagination and some early film imagination. The War of the Worlds imagined invasion literature on an interplanetary scale, and it wasn’t long before motion pictures contributed to the imagining.

Who knows what lurks in the night skies?

If you’ve ever been outdoors at night, in total darkness, under a cloudless sky, much of what you see is the past, pinpoints of light traveling from far away locations in the universe over many Earth years, often from a time before there was an Earth.

In the night sky, the points of light vary in brightness. Sometimes they appear stationary. Sometimes they appear to change intensity, maybe sparkle momentarily, but mostly they are just there, stationary. But watch long enough and you’ll notice that relative to you they change position very slowly, almost imperceptibly.

And occasionally you might see something different. A narrow streak of brightness moving quickly across the sky, or a point of light that seems to move or pulsate, something curious. Maybe a meteor, maybe a comet, or maybe a satellite. Or maybe it’s something else. So you keep watching. In the darkness we are always drawn to the light.

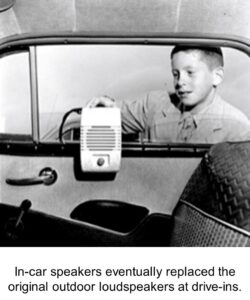

It’s the same at the movies, the lights dim to almost darkness, the curtain rises or the curtains part (or at least they used to) and the light and moving images begin, and we are drawn in. Whether we’re sitting inside a movie theatre or in cars and trucks under the dark night sky at the drive-in, we are drawn to the light and the images. And in the 1950s, before more and more people stayed home watching television, there were a lot of movie screens. And many of those screens were showing science fiction and outer space films.

Weekly attendance at movie theatres in the United States probably peaked in the 1930s and 1940s at around 80-90 million moviegoers per week. Attendance dropped significantly in the 1950s and 1960s but there were still somewhere in the range of 40-50 million moviegoers per week at the many thousands of movie theatres. Today there are about 40,000 movie screens in the United States and about 1,700 in Canada.

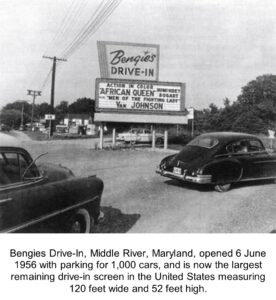

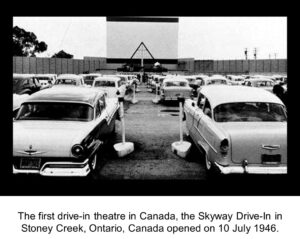

Then, by the late 1950s, there were over 4,000 drive-in movie theatres in the United States and over 240 in Canada.

Dark theatres and the dark nights at drive-ins were perfect locations for watching outer space science fiction films.

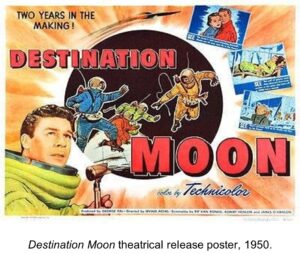

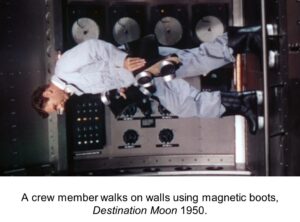

George Pal, legendary Hungarian-American producer and director, made many of those early outer space sci-fi movies. Destination Moon, produced in 1950, was one of the first of those (and the first in Technicolor). It was also the first US feature to realistically explore the engineering and scientific aspects of space travel. It also anticipated today’s space travel entrepreneurs (Musk, Bezos, Branson) involving a group of private investors funding and building the first lunar spacecraft. Using an atomic powered spacecraft, the crew experiences its first spacewalk to free a frozen antenna. A crew member rescues another who goes overboard by using an oxygen tank as a jet pack in the rescue (a scene that has been replicated many times including in 2001: A Space Odyssey). Their lunar landing is successful, but they’ve used up too much of their fuel to depart successfully. Mission control tells them that in order to lighten their weight one crew member needs to remain on the Moon. But they avoid that fate by ditching the spacecraft’s radio system and a space suit to lower their weight. All edge of your seat stuff!

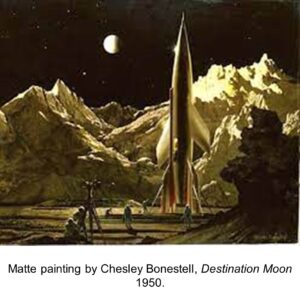

Another legend, the astronomical painter Chesley Bonestell, produced the amazing matte paintings used throughout the film which won the Academy Award for Best Special Effects.

While Destination Moon was Hollywood’s (and Pal’s) first major outer space sci-fi Technicolor feature film, Pal is known for other great space sci-fi films including: When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), Conquest of Space (1955), and (although not an outer space film) The Time Machine (1960). More on some of these later.

There’s an interesting side-note: Walter Lantz was a great friend of Pal’s and he was also the creator of the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker. All of Pal’s movies feature an appearance of Woody Woodpecker somewhere in the story. When asked during an interview in 1979 which film was his favourite, Pal’s reply was “The next one”.

The golden age of sci-fi

The 1950s are often called the classic or golden era of science fiction motion pictures. The ‘classic’ or ‘golden’ were memorable, passed the test of time, captured the hearts and minds of a past generation, and still challenge the minds of present generations.

Somewhere around 200 science fiction films were made in the 1950s, about 20 a year. Two of these were outer space sci-fi films that won Academy Awards, Destination Moon (1950) and The War of the Worlds (1953), both produced by George Pal. And there were many other outer space sci-fi films among the 200. Many were low-budget, often poor quality or amateurish, and gimmicky. Often they reflected the fears and hopes of the day, including fear of invasion by the cold war combatants or aliens. Fear extended to nuclear weapons and new weapons yet to be developed, or futuristic weapons of alien civilizations hostile to humanity. Among the fear was the hope that humanity would overcome adversity and survive to explore and discover the wonders of the universe.

All of these movies affected popular imagination as no other form of media had done previously. In 1950 the average price of a movie ticket was 46 cents, equivalent to about $5 today. In 1960 the average movie ticket price was about 69 cents, about $7 today. In 2021 there were about 9.5 million moviegoers per week in the United States and Canada. In the 50s and 60s that number was closer to 60 million movie-goers per week. Of course, today we have DVDs and online streaming so movie ticket sales don’t tell the whole story. But still, popular exposure to motion pictures in the 50s and 60s was huge.

In the 1950s the movie industry was producing about one film every two weeks. A lot of people were watching a lot of science fiction, maybe half of which could be considered outer space sci-fi films. Some of those were great, some good, some atrocious, some unintentionally funny, some funny by design, and some were complete spoofs. But who said outer space sci-fi couldn’t also be fun, even accidentally.

While the1960s produced some excellent sci-fi films, the decade did not see the rush in numbers that the 50s had produced. About 100 science fiction films were produced in the 1960s, some of them great and about half involved outer space.

Of course, it would take a book or two or three to review all of those outer space science fiction movies, so let’s have a look at some of the most memorable, all of which made an impression, some good, some bad, and some ugly.

Visitations by aliens good and bad

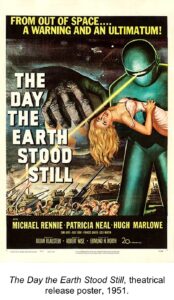

In 1951, the same year that Destination Moon was released, one of the all-time great sci-fi films from the 50s was also released, The Day the Earth Stood Still. It was directed by Robert Wise (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, The Andromeda Strain, The Haunting, The Sound of Music) and starred Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe and Sam Jaffe. An alien craft (saucer shaped) lands in Washington D.C. carrying humanoid goodwill pilot Klaatu and a robot named Gort. Their mission is to tell the people of Earth that they must live peacefully or be destroyed as a threat to the rest of the universe.

At the time, the Cold War and the nuclear arms race were heating up. The Day the Earth Stood Still is powerful and yet gentle. It has been described as timeless and influential, an outer space science fiction classic that melds the ordinary and the fantastic. The screenwriter Edmund North saw a subliminal Christ comparison in the Klaatu character. Author Arthur C. Clarke listed it as one of the 12 best science fiction films of all time. Maybe the final words spoken by Klaatu sum it all up. Before he departs the Earth, and after Gort sets out to destroy all of humanity with near success, Klaatu tells us: ”Your choice is simple: join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration. We shall be waiting for your answer.”

An interesting side note: In the movie, Klaatu visits Professor Barnhardt (the world’s greatest living person) asking him to bring together the world’s greatest scientists to warn the people of Earth of the dangers of continuing on their warlike path. (Barnhardt is played by Sam Jaffe who earlier in his life had been dean of mathematics at the Bronx Cultural Institute.) The equations on the blackboard in Bernhardt’s home are authentic physics describing a particular form of the famous “three-body problem” in Newtonian gravitation, a problem which has no general closed-form solution. These many-body problems are central to navigation in interstellar space. The manner of writing and organization of the terms show that a real physicist had produced the work.

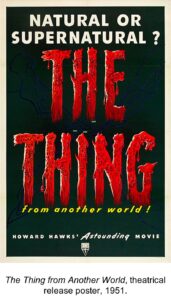

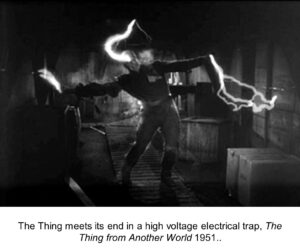

Another highly rated sci-fi film from 1951, The Thing from Another World, again deals with an alien visitation to Earth, but this time by a malevolent plant-based form of alien life rather than the humanoid good-willed Klaatu.

An Artic-based US Air Force and scientific team discovers a crashed flying saucer (another saucer!) and near it a humanoid body frozen in the ice. They bring the body back to thei r base still in a block of ice. But the block is accidentally defrosted by a team member who covers it with a blanket to hide the disturbing appearance of the creature. Not realizing the this is an electric blanket and is still plugged in (oops!) the block melts and the creature escapes while being attacked by the team’s dogs. Things go downhill from there. A storm is on the way, the alien can survive on human and animal blood, and stalks them all. The team rigs up an electrical trap which the alien walks into and is killed. When the storm ends the team broadcasts a warning by radio as the movie closes: “Tell the world. Tell this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies…”. What an ending! And definitely, people were watching the skies.

Directors Ridley Scott, John Frankenheimer, Tobe Hooper, and John Carpenter all cited The Thing from Another World as a key, influential film in their lives. Carpenter re-adapted the film in 1982 as just The Thing.

Humans visit outer space

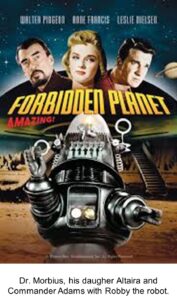

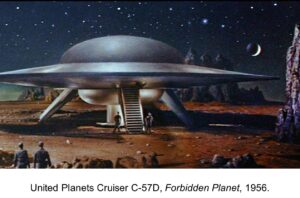

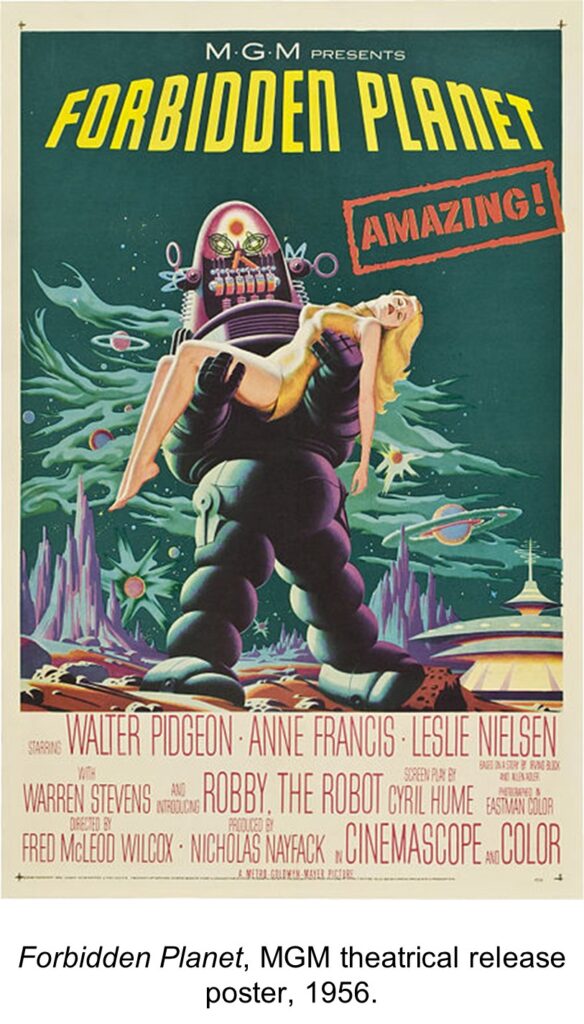

In the 1956 release of Forbidden Planet, instead of aliens coming to the Earth a human starship, the United Planets cruiser C-57D and its crew, travel to the distant planet Altair IV in the 23rd century. Their mission is to investigate the silence of the planet’s human colony. They find just two survivors (Dr. Morbius and his daughter Altaira) and a powerful robot named Robby. They also discover the deadly secret of a lost civilization. Distributed by MGM and nominated for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects at the 29th Academy Awards, Forbidden Planet was a gem from this golden age of sci-fi movies. It received then and still receives outstanding reviews and seems to get better with age. It was nominated by the American Film Institute for their top 10 science fiction films.

On Altair IV, Dr. Morbius discovered a great power and a does not intend to share it with anyone. This power was created by a highly advanced but now extinct race called the Krell. The power itself is based on a vast machine powered by 9,200 thermonuclear reactors under the earth and it allowed the Krell to create anything by mere thought. But the Krell forgot one thing, their subconscious thoughts. which resulted in the creation of great monsters from the “id” (the dark, inaccessible part of their personality).

Most of the crew and Altaira are eventually able to escape and activate the planet’s self-destruct system. The film closes with starship commander Adams telling us that in about a million years the human race will become like the Krell, and these events will remind them they are, after all, not God.

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry was quoted as saying that this film was a major inspiration for the Star Trek series. Interestingly, the plot of Forbidden Planet also appears to contain analogues to aspects of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

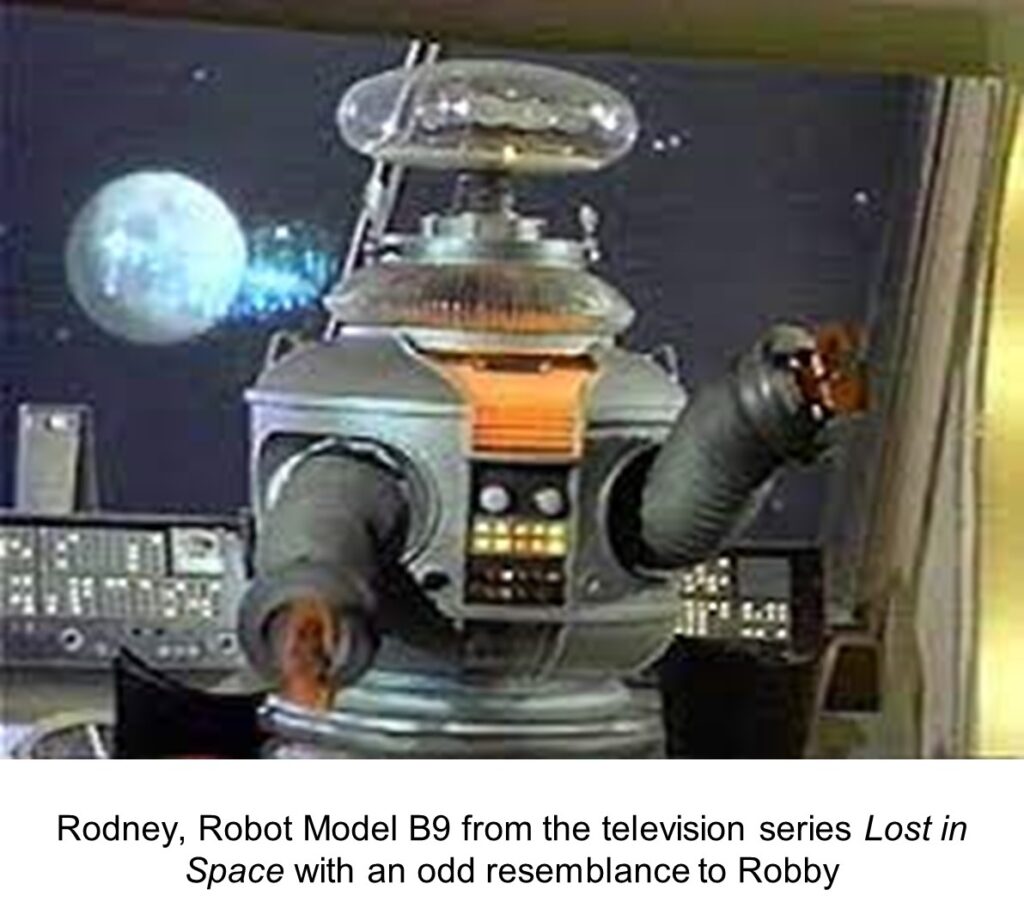

Have another look above at the theatrical release poster for the film, showing the menacing robot (Robby) carrying a struggling pretty girl (Altaira) – have you noticed how often this theme of a menacing alien or menacing creature (or robot) carrying a “damsel in distress” shows up in movie posters from the 1950’s? And doesn’t the robot (below, sometimes called Rodney or Robinson Robot or B-9) from the television series Lost in Space have a striking resemblance to Robby?

Forbidden Planet was an expensive production in the 1950s. The production budget was about $2 million (the cost of Robby alone was about $125,000!) with a total box office take in the year of its release of about $2.8 million.

The Martians are coming!

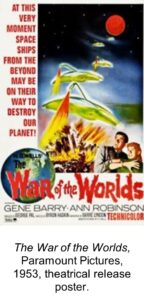

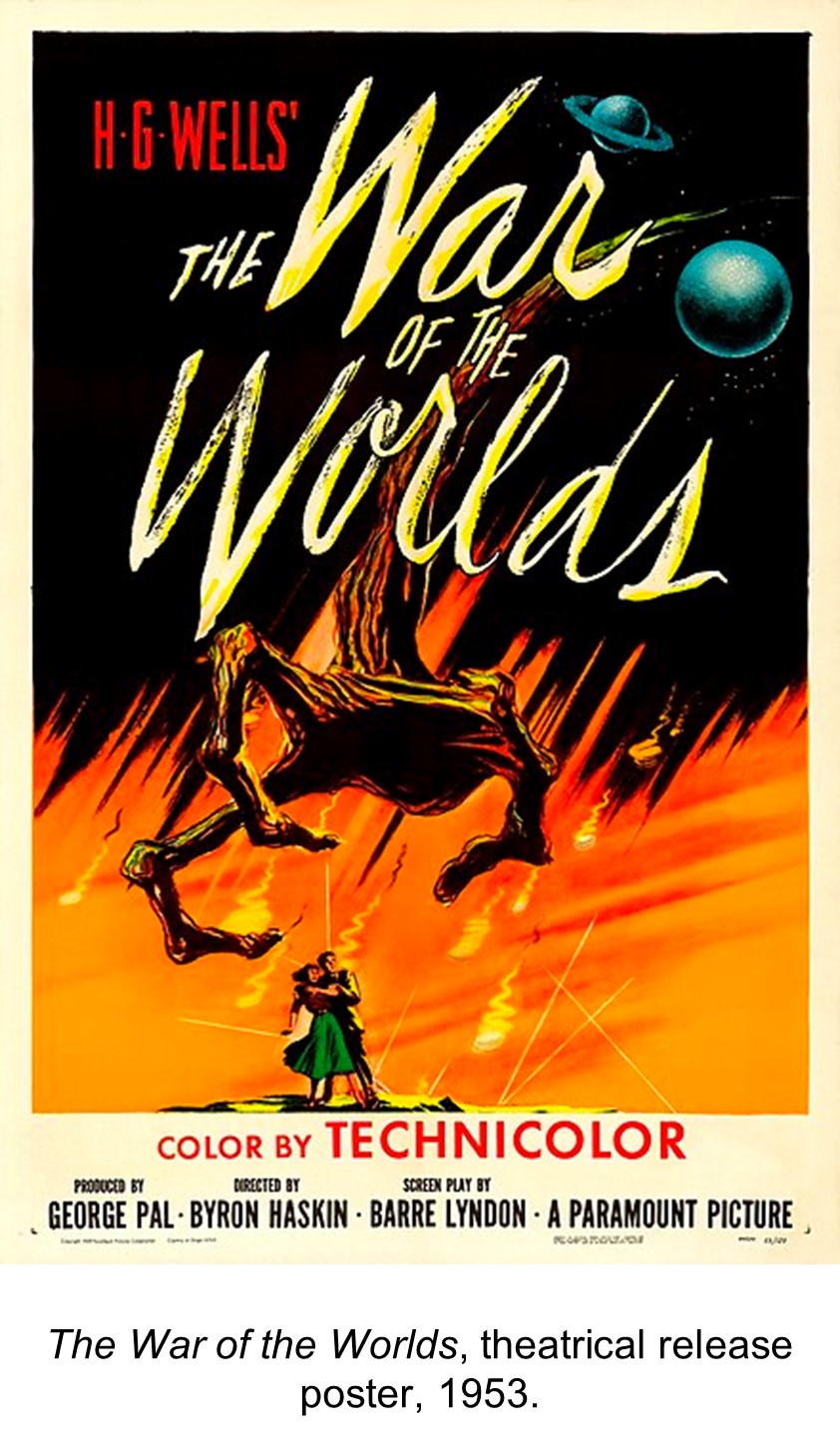

Prior to Forbidden Planet, in 1953, the outstanding Technicolor film The War of the Worlds was released by Paramount Pictures. In part 1 of this series of articles and at the beginning of this article a lot was mentioned about the novel The War of the Worlds. This film is a retelling of that novel set in 1953 southern California about an Earth invasion by Martians. It was nominated in a number of Academy Award categories and won for Best Visual Effects that year. In 2011 it was selected for the US National Film Registry in the Library of Congress as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

The residents of a small town in California (Corona, California was the shooting location) are surprised and excited when a burning meteor lands nearby. But their excitement turns to horror when they discover that it is carrying beings that did not arrive in friendship.

It was directed by Byron Haskins and produced by George Pal (yes, George Pal), with Chesley Bonestell’s paintings from the 1949 book edition of The Conquest of Space appearing at the beginning of the film depicting the planets in the Solar System. Most of the filming took place on Stage 18, the largest stage at Paramount Studios which (odd coincidence) is also where all the Star Trek movies and some of the TV episodes were shot.

In the story, scientist Clayton Forrester and Sylvia Van Buren are the first to arrive at the site of a meteorite crash.

Soon an alien war machine emerges and begins killing at random. The Martians unleash an assault on Earth, with hundreds of invulnerable ships. The invasion occurs across the planet and the major cities are destroyed one after one–even the atomic bomb can’t stop them. Forrester and Van Buren are able to wound one of the aliens and obtain a sample of its blood for testing in the hope of discovering aliens’ weakness. If humans can’t beat them, who or what can? Perhaps it would be something much, much smaller. In Washington, the Secretary of Defense prepares to order the dropping of an atomic bomb on the Los Angeles-area Martian nest.

Forrester and Van Buren discover that the Martians are anemic and have a very underdeveloped immune system. Humans everywhere flee for their lives, when suddenly the alien ships begin to crash and the aliens begin stumbling and dying. Because of their weak immune systems, when they are exposed to Earth’s atmosphere they became infected with biological pathogens that humans are immune to but Martians are not. The alien invasion stops and the aliens fall and die where they are, the pathogens being uniformly fatal to them.

The film was a critical and box-office success and 1953’s biggest sci-fi movie hit. It had an immense effect on popular imagination, when the Cold War and atomic weapons loomed large. And remember Woody the Woodpecker? The cartoon character of Woody appears in a treetop at centre screen when the first Martian ship crashes through the sky.

Destination Moon, The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Thing from Another World, Forbidden Planet, and The War of the Worlds are all great examples of some of the 1950s golden age of outer space science fiction, and there are others: When Worlds Collide (1951), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (a 1956 favourite), The Blob (1958 with Steve McQueen), It Came from Outer Space (1953), Invaders from Mars (1953). There were other examples that were special in their own kind of way.