By James Myers

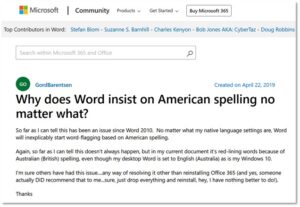

The BBC’s report this week on “The Surprisingly Subtle Ways Microsoft Word Has Changed the Way We Use Language” highlights the effects of technology on human behaviour (or “behavior,” as Word would spell it).

The American-made Word, used in 1.4 billion devices each month, provides an example of how technology is standardizing (or as some humans would spell it, “standardising”) our languages. There is nothing wrong with the spelling of “behaviour” or “standardising,” but the technology now gives us no choice – it tells us both of those spellings are incorrect, notwithstanding that both have been long in use in Britain (where the spellings originated), in Australia, and in Canada. Far longer in use, in fact, than Word’s “correct” versions.

I am a Canadian who takes a great deal of meaning from the origins of a word, as outmoded (as judged by the technology) as I might have become. When the symbols that make the word – which are the letters used to spell the word – change, I lose some of the meaning.

Technology is being used to standardise our languages, presumably for technological convenience, and in the process is moving us to phonetic spelling and away from a spelling that provides far more information about the words.

Not a big deal, you say? But how will we be able to understand our own history, which tells us how we arrived at this particular point in space and time and where we are headed, if we lose the historical memory that’s embedded in the symbols of our languages? I’ll provide some examples.

Why, for example, does Microsoft’s Word tell me I am wrong when I spell licence – and by this I mean the driver’s permit in my wallet – with a c instead of the phonetic s? Why did Microsoft license the software (notice here that I used an s instead of a c) to judge me wrong, when I spelled the physical item with a c? The fact is that “licence” is a noun and “license” is a verb, and the spellings differentiate the distinct purposes of the two words in language. Therefore, I am “licensed” to carry a “licence” in my wallet.

The Origin of a Word is a Type of Information Easily Lost in Standardisation.

Consider the “cheque” that I write on my bank account to pay a supplier. Fascinatingly, the word “cheque” originated centuries ago, from the “exchequer” which, in England, was a large table with a raised edge modelled (oops, sorry Word, maybe I should have written “modeled”) after a chess board (French: échiquier), which held counters used to calculate values for taxes and goods. Hence, the origin of the word spelled “cheque” explains why I use those six symbols for a written promise to transfer my money to a supplier.

What information do I get from the word “check” when it’s used for phonetic simplicity in place of cheque? There is no intrinsic meaning to “check” as a paper promise that’s honoured by banks. A future generation will have no idea why we now use, as Word instructs, the five symbols c-h-e-c-k, in place of the six c-h-e-q-u-e, for the paper promises we wrote to pay for our purchases. And, even now, will you know what I mean when I write “I checked to ensure that I had checked the right option for the check”?

A Challenge in Standardisation is that Applying a Word in the Correct Context Requires Understanding of the Time When It’s Used.

I’ll give an example of meaning embedded in words that changes over time. When I was growing up, my great-aunt, who was born in 1907, would declare “I feel queer” when she was sick with a flu. Back then, being queer was definitely not a good thing, and until recently the word was used as a terrible slur, to segregate known or suspected gay people from common society like a racist segregates people of different skin colour. Honestly, that’s what it was like to be called a queer, back when I was growing up. How will future generations remember that history – so that it does not repeat – now that the word has been given a meaning that’s good and natural? Future generations might wonder why my great-aunt said she felt good and natural when she had a fever.

Or, even worse, they might think that my great-aunt was prejudiced against gay people because she used the word queer for sickness. If that’s what they will think, they would be misjudging her. The challenge for the word standardisers is in tracking the definitions of a word at a particular time. Consider the Oxford English Dictionary’s 1976 definition of “queer” which made no positive association to gay people: “1. Strange, odd, eccentric; of questionable character, shady, suspect; out of sorts, giddy, faint, (feel queer).” The OED’s definition continued by indicating the associated slang uses of queer in 1976 as either “drunk” or “(especially of a man) homosexual.” Thus, in that time, the word was used not as a compliment but as an insult.

It’s too easy to cast judgment on the past when using present standards.

The point is that my great-aunt did not abuse the word when she declared that she felt queer. We should be careful when we judge our ancestors and their motivations by the expressions they used back then, to ensure we understand the contexts in which they used the words and the meanings they intended at the particular time, which could be very different from the conventional meaning in the present.

A big part of the information contained in our symbols is about the time in which the symbols began to be used, such as in the word “cheque.” That information, and our memory of time, can be erased in the process of standardization.

And, therefore, I will continue to ignore Microsoft Word’s verdict on my use of “licence” and “cheque” and a host of other words that I apparently now misspell. I am proud to differentiate myself from the technology.