The questions raised by the U.S. $31 trillion national debt

How do we account for debts that will never be repaid? When we continue to trade in debts that have no cash value, what does it say about our system of belief?

The headlines recently featured the U.S. national debt, which is now over $31 trillion. The accumulated liabilities of the U.S. government now exceed by 35% the country’s entire annual gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately $23 trillion.

If the U.S. can maintain its historical mean annual GDP growth rate of around 2%, somehow convert all of it to cash, and apply 100% of that growth to debt repayment, it could in theory generate enough cash over the next 66 years to clear the liability.

Theory, however, is not reality. It is both a mathematical and political impossibility that $31 trillion of debt will ever be repaid in cash – and yet we continue to trade government debt as an asset. An asset is defined as something that has a realizable “future value”. What is the future value of a liability that the debtor will never have the cash to repay?

The Impossibility of Cash Repayment

There would be enough cash to repay the $31 trillion debt in 66 years in the future if, and only if:

- Every single penny of future growth goes to repaying past debt from now until the year 2088. For about three generations, citizens will receive absolutely none of the growth. All of the growth will go to the government so it can repay the debts that accumulated in the 246 years from 1776 to 2022, but mostly in the past 20 years.

- No further debt is added, meaning no more annual government deficits because taxes and other revenues will be sufficient to cover both public spending and interest payments on the debt. This would require either a 50% increase in current income tax rates or an immediate cut of $1.3 trillion to balance the 2023 U.S. budget. That tax increase or spending decrease represents the amount currently spent on Social Security, and close to double the U.S. defence budget. Balanced budgets will be required for the next 66 years.

Can you imagine such self-restraint, over three or more generations, each generation maintaining the pledge made in 2022 to clear the slate of debts for past consumption? Can you imagine what it would be like for citizens to forego any personal benefit from a growing economy, beginning now and lasting until 2088?

It’s unimaginable. Nowhere in the world does such political will exist, nor has such will ever existed. There will never be enough cash to repay the $31 trillion debt because there is no conceivable way to achieve such a feat, either economically or politically.

In the past 100 years, the debt multiplied nearly 76 times, from (in current dollars) $408 billion to $31 trillion. In the past 40 years, the debt increased by about 775%, which includes a tripling in the past 20 years. Assuming the world’s current economic systems persist, it seems likely that debt will continue to multiply. The only way the U.S. government can repay its debts when they become due is by selling more debt to raise the cash. Money from future debt issuances will pay the those who bought debts in the past. It’s a perpetual mortgage on future cash flows.

Trading in Belief

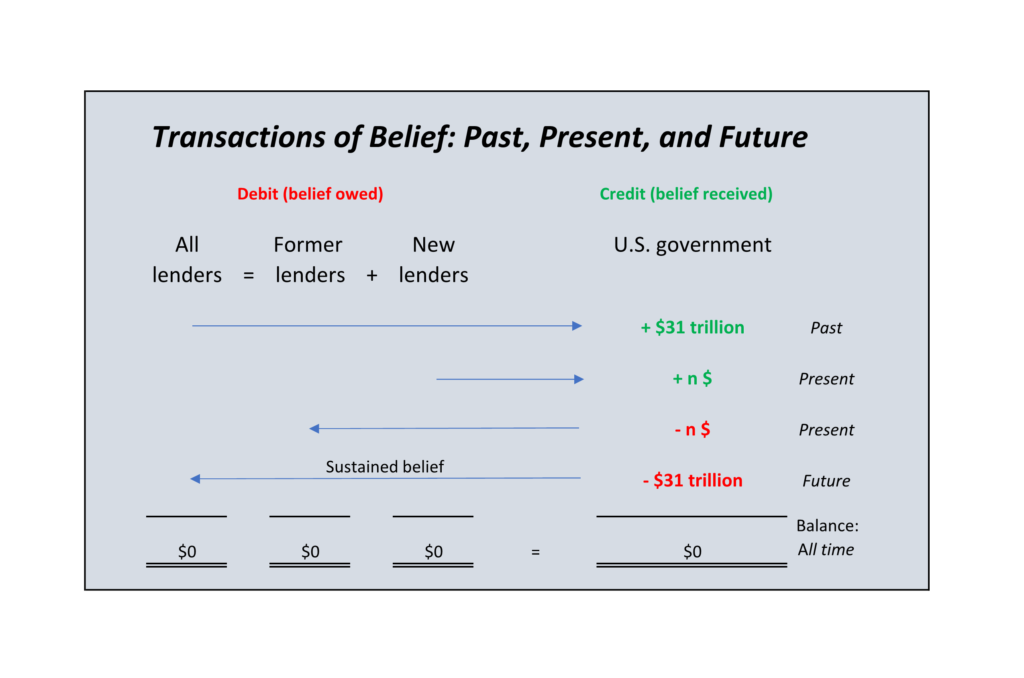

Since there will never be enough cash to repay the debtholders, what they own is not really a liquid asset but what we accountants call “equity”. The equity they hold is a long-term investment in the future potential of the U.S. government and by extension of the citizens of the United States.

U.S. government bonds, treasury bills, and other “debt” instruments are presently accounted for and traded as risk-free assets. “Risk-free” means that the traders who buy government debt in the markets think there is no uncertainty that they will receive repayment in cash. Given the mathematical and political impossibility that the government will ever make up the $31 trillion cash shortfall, however, should uncertainty and risk really be at a maximum rather than minimum?

With certainty, $31 trillion of cash will never be raised for repayment and so buyers and sellers of government debt are trading in belief which is inherently uncertain. Nonetheless, the traders believe in the future potential of the United States government and people, and they place a value on this belief which is how U.S. government debt is priced in the markets.

Even if by some miracle $31 trillion of cash were to be raised – say the U.S. government mints a $31 trillion coin and gives a piece of it to each creditor – the value of the debt would still be based on belief. That’s because there is no intrinsic value to money. We assign value to money only because we have a shared belief in it as a medium of exchange. The paper bills, metal coins, or digital bits that we exchange as “money” have no value in themselves – they are neutral – but they provide a measure of the value of the object that we trade.

Sustaining belief

The debtholders don’t own a cashable asset, instead they hold and trade a permanent investment in the U.S. government. The only value of the debt is in its tradability, which depends on the willingness of future buyers to part with their own cash to acquire a promise of the U.S. government to honour its debts. The government’s promise has no cash value. For present traders in debt, the only value of the government’s promise is in the belief that it will be honoured in the future.

If there are no buyers who believe the US government will honour its debts, the debt will not be tradable and have zero value to the sellers. Any value in trade requires belief on the part of the buyer.

Presently, there continue to be buyers who believe in the future potential of the government’s promise. The buyers believe so strongly in the permanence of the United States and the commitments of its government that they have provided $31 trillion of their own capital to the potential of the future.

Will the belief of present and future debt holders begin to weaken at some point? Will there come a time when there will be no market for the government’s promise of repayment? How can belief be sustained over time, for the government to raise more debt in the future to repay debts incurred in the past?

Threats to Belief

Would repeated citizen storming of the legislature shake the confidence of future traders in government debt? How about more government shutdowns, when the legislature refuses to provide funding for committed expenses? Or more transfers of wealth to the top 1% of citizens who, from tax cuts and economic circumstances, now hold about 25% of the national wealth – would the debtholders demand some of that transfer? What does increasing social unrest from violence, racism, and political polarization do to belief in the country’s future potential? How greatly will belief be weakened by the continued rapid decline of citizen faith in the ideals of democratic self-governance, as elected representatives cast doubt on the electoral process?

Unregulated cryptocurrencies not supported by government promises or general acceptance as a medium of exchange are, of course, traded on belief. A rise in cryptocurrency value relative to the value of a national currency is a strong signal of a weakening of belief in the government’s promises. Inflation is another strong signal of fading belief in future potential.

We might wonder if the creditors will draw a line at some point in time, beyond which they are no longer willing to trade in the belief that the government will honour its promises. Would the buyers draw the line at $32 trillion? $50 trillion? $100 trillion? Nobody knows.

With such uncertainty in the meantime, would it not be prudent and wise to strengthen belief in future potential?

Strengthening belief would require the political will to acknowledge and fix the threats to belief, before it is too late.

Once it is broken, belief disappears very quickly and it’s not easy to restore. The history of hyperinflation in a number of countries demonstrates this fact.

The time to strengthen belief is in the present, not the future. The question is what steps should be taken now to ensure the government continues to be worthy of credit?

The answer, whatever it is, requires the general agreement of the citizens.