Google headquarters in Mountain View, California. Image: Noah Loverbear

By James Myers and Mariana Meneses

Have you considered how much a single advertising company that provides 90% of the world’s web searches affects the way we think, and the knowledge we produce and consume?

Searching the web for information, or “googling” as it’s often called because the vast majority of searches rely on Google, is now indispensable to daily living.

Governments put essential information for citizens on the web, and practically all of us as consumers rely at some point on the web to inform, order, or download purchases. Imagine life in 2024 if we couldn’t search the web for information (like it was only twenty years ago): we simply couldn’t function in today’s economy.

Every Google search, and every use of Google’s other services, provides an input to the company’s database of information. However, Google’s outputs – whether in search results, YouTube recommendations, or otherwise – reflect more than the information input by human users.

Many, but not all, who use Google to find information understand that the word “Sponsored” in the first results that Google serves up means that they are paid ads. Few, however, know the many other ways that Google’s algorithms and website designers work together to establish the order in which search results are presented. The operation of the company’s algorithms is part of the world’s information that Google does not disclose to its billions of users.

Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” but the company does not disclose the many ways its algorithms “organize” information and make it “useful.” Clearly, the information is organized in a way that drives tremendous profit for Google. In 2023, Google’s parent company Alphabet Inc. reported a profit of $74 billion on $307 billion of revenue, 77% of which ($238 billion) was from advertising.

“So, what’s the big deal? I don’t pay for Google, and it gives me information. Isn’t that a fair trade?”

Many Google users might see their exchange of inputs for Google’s outputs this way, without considering the longer-term effects on their own behaviour and thinking that result from Google’s algorithms generating the outputs. Highlighting the serious mounting concerns, the U.S. Government is challenging Google on its use of algorithms to create anticompetitive results for consumers and advertisers.

In January 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it was suing Google for monopolizing digital advertising technologies “that website publishers depend on to sell ads and that advertisers rely on to buy ads and reach potential customers. Website publishers use ad tech tools to generate advertising revenue that supports the creation and maintenance of a vibrant open web, providing the public with unprecedented access to ideas, artistic expression, information, goods, and services.”

The Guardian reported in 2021 on Google’s use of its market dominance to in threatening to cut off the flow of information to 27 million Australians over proposed legislation the company disagreed with.

The U.S. Government’s lawsuit, which was joined by the Attorneys General of eight states, seeks to restore balanced outcomes for consumers and advertisers who rely on the information that Google provides, claiming that:

“Over the past 15 years, Google has engaged in a course of anticompetitive and exclusionary conduct that consisted of neutralizing or eliminating ad tech competitors through acquisitions; wielding its dominance across digital advertising markets to force more publishers and advertisers to use its products; and thwarting the ability to use competing products. In doing so, Google cemented its dominance in tools relied on by website publishers and online advertisers, as well as the digital advertising exchange that runs ad auctions.”

As reported in Wired Magazine, one example of an outcome that the government’s antitrust case seeks to overturn is a fee paid by a Google user for a New Zealand travel visa at more than double the required cost after unknowingly clicking on a promoted link rather than the official government site. The number of such errors could be overwhelming, considering that Google processes an estimated 5.9 million search requests every minute of every day, as reported by search engine optimization company Semrush.

The trial of the alleged Google monopoly will be heard by a jury this September.

Another case against Google highlighted the recommendation algorithms of Google-owned YouTube, which pays users to post popular videos.

In Gonzalez v. Google LLC, the family of Nohemi Gonzalez, an American who was one of 130 killed in ISIS-coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, alleged that YouTube’s recommendation algorithms promoted ISIS and provided financial benefits to the terrorist organization. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case on the basis of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which exempts internet platforms from liability for hosting third-party content. However, Section 230 was modified in 2018 to constrain hosting of sex-trafficking sites, raising the question of whether the legislation could be further amended to prevent hosting of terrorist content.

There’s a problem with data fidelity when the outputs differ from the product of the inputs.

We input a tremendous amount of data to Google, which collects information on our activities through its search engine and ubiquitous products YouTube, Gmail, Chrome, Android, Google Maps, and third-party data sharing agreements. The company maintains a data file on everything you do while you’re logged into its services, and it also gathers metadata on activities of those who use services without logging in.

While Google doesn’t compensate users for their data, the company pays substantial sums for access to user data. A witness in the U.S. government’s antitrust case against Google revealed that Google pays Apple 36% of search ad revenues generated by Apple’s Safari browser, in exchange for Apple making Google the default search engine in Safari.

What are the other ways that Google’s outputs can change our behaviour and thinking with its algorithms?

Google finds and categorizes information with a two-step process.

First, Google’s crawlers, like Googlebot, scan webpages for information including text, images, and videos. Website designers can boost the discovery of their pages by providing clear links and sitemaps. Second, Google categorizes the information in its database, making it searchable. The more relevant and high-quality Google deems a webpage to be, which provides an advantage to sites with better financial and design resources, the more likely the page is to appear in a user’s search results.

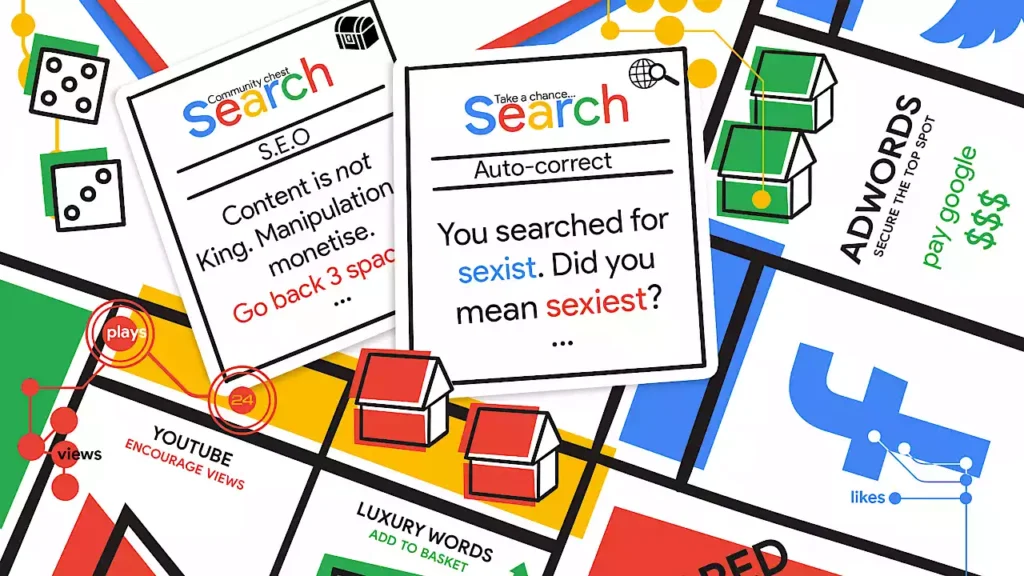

Google doesn’t disclose the criteria that its crawlers and algorithms use to locate and categorize information. However, Google’s influence on how we find information has led to the widespread practice of Search Engine Optimization (SEO), which involves designing website content to get Google to boost its visibility. This can result in website content created with the specific aim of its being found and prioritized by Google’s search algorithms, and informational value can become a secondary concern.

SEO is a complex process of optimizing website elements such as content and structure to make it more attractive to Google.

SEO techniques include the liberal use of links to popular and authoritative sites and keywords that appear most often in user queries. Other SEO techniques include strategic use of webpage tags, metadata, and mobile-friendly design to gain a relative advantage over competitors in the quantity and quality of website traffic. Web designers can pay to license SEO optimization software like Yoast, which uses its own algorithms to analyze content and suggest improvements to increase the website’s visibility and search ranking.

Although search engine optimization is considered among defensible ‘white hat tactics’, SEO tactics raise concerns about conformity in website language, limitations to imagination, and adherence to Google’s undisclosed algorithms which the company periodically changes.

No spam, please! Image: Indolences

By contrast, SEO manipulation refers to the use of ‘black hat tactics’ to trick search engine rankings and gain an unfair advantage over competitors.

For instance, Google’s SEO Starter Guide explicitly states that “keyword stuffing,” which is the indiscriminate use of frequently-searched keywords in sites, goes against the company’s spam policies. By engaging in these tactics, websites can draw unwarranted attention from Google’s crawlers and categorization algorithms and manipulate outcomes in web searches.

Spamdexing is a form of SEO manipulation also known as search engine spamming. It involves creating web pages with irrelevant or repetitive keywords in an attempt to trick search engines into a higher ranking of the website, leading to a decrease in the quality of information output in response to a search input.

Another manipulative tactic is cloaking, where the website presents different content to the search engine and the human user, making it difficult for search engines to determine the site’s relevance. Link farming is also used, where a group of websites link to each other to artificially increase their page rankings. Other tactics include hidden text, doorway pages, and article spinning. All of these methods are designed to manipulate search engines into a higher website ranking, and distorting information output to users.

Hidden text is a black hat SEO tactic that involves inserting text into a web page that is hidden from users but visible to search engines to manipulate search rankings.

Article spinning is a technique used by spammers to create multiple versions of the same article or content by changing words, phrases, or sentence structure, while retaining the same meaning. This creates multiple linked articles posted on different websites to improve search rankings, although often with grammatical errors and awkward phrasing that degrades the quality of information.

Google and other search engines have adjusted their algorithms to detect article spinning, penalizing a website by exclusion or a significant drop in search rankings. The algorithms are also on the lookout for spamdexing, which gained attention as early as 1998 in an article by Professor Ira Steven Nathenson, now with the St. Thomas University College of Law.

The consequences of manipulated outputs are far-reaching.

The Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME) is a theory that suggests search engines can sway consumer and voting preferences with manipulated outputs. A 2015 paper published in the journal Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, by Robert Epstein and Ronald E. Robertson, reports on five experiments conducted with over 4,500 participants in the U.S. and India demonstrating the effectiveness of SEME.

The 2020 election in the U.S., with conspiracy theories still widely circulating that the result was illegitimate, presents an example of the effects of informational manipulation. A 2022 study by two doctoral candidates and five co-authors at the University of Washington examined 800,000 election-related headlines and concluded that videos “are the most problematic in terms of exposing users to delegitimizing headlines.” YouTube, which is owned by Google, is the world’s largest distributor of video content.

Words as Data: The Vulnerability Of Language In An Age Of Digital Capitalism by the Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats warns that: “The language that flows through the platforms and portals of the Web is increasingly mediated and manipulated by large technology companies that dominate the internet, and in particular for the purpose of advertising by companies such as Google and Facebook.”

Aligning the world’s data outputs with its inputs is a difficult but critical task that we now face.

The road ahead will not be easy, particularly in a year like 2024 when half the world’s population will be casting votes in elections.

Regulatory actions like the European Union’s landmark 2016 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the newly-enacted EU AI Act, combined with legal challenges like the U.S. Government’s antitrust suit against Google, can restore some balance to the world’s index of data.

The next logical step may be to require disclosure of key search engine algorithmic functions and recommendation algorithms like those used by YouTube, as well as periodic changes to their codes. Google has resisted disclosure on the basis that it would put the company’s profitability at risk, an argument that was the basis for the judge presiding over the U.S. Government’s antitrust case to seal some of the evidence from public view.

It could be possible to further guard against manipulation by websites through search engine optimization and other tactics if search engines like Google increased transparency with their ranking algorithms and policies.

Curtailing the practice of paying for default browser access, as Google did to Apple, could help to promote competition from other browsers and offer consumers more options for the security and use of their data. Browsers like Firefox, which is provided by the non-profit Mozilla Foundation, lack advertising profits to pay for default access and are left with a very small potential market share as a result.

Last September, Google announced that all U.S. election advertisers must “add a clear and conspicuous disclosure starting mid-November when their ads contain AI generated content,” although the company was silent about advertising for 2024 elections involving billions of voters outside the U.S. With the rapid increase of algorithmically-generated information proliferating on the internet from sources like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard, as well as convincing deepfake images, search engines and recommendation algorithms will have to contend with disclosing non-human outputs.

While Google has undoubtedly revolutionized access to vast amounts of information, it’s essential to recognize that at its core it’s an extremely profitable advertising company. Therefore, it’s crucial that its profit-driven actions remain transparent and accountable to billions of users who depend on it.

In the final analysis, Google’s profitability could prove more sustainable with an increasingly natural balance between its human inputs and the company’s outputs. And that would be a win-win scenario for all.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Ancient Civilizations of The Future: Could Technologies for Preserving Individual Memories Define Us In a Million Years?

- Emerging Issues in Space Governance Urgently Require International Agreement

- Update on Global AI Regulations: With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

- Burning Museums and Erasing History: The Societal Need for Memory