Image by Tumisu, on Pixabay.

By James Myers

It’s no secret that most users of online services don’t fully read or understand the legal wording of lengthy user agreements and privacy policies, which are increasingly broad in their scope.

We survey some of the emerging issues with online user agreements and privacy policies. We also look at some recent regulatory changes that are providing greater consumer protection, while standards in many jurisdictions are drawn from Section 230 of the U.S. Communication Act of 1934. Section 230 continues to provide broad legal immunity to websites and social media platforms hosting third-party content.

The average person is subjected to many contracts for the use of online applications that are either helpful or necessary in a technological era, when much of what we do and transact is now online. But how many of us read those contracts?

One revealing study, published in 2020 by Jonathan A. Obar of York University and Anne Oeldorf-Hirsch of the University of Connecticut, provides an answer. Entitled “The biggest lie on the Internet: ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services,” the study presented a fictitious social media website to 543 participants and observed their reactions to the site’s terms of use and privacy policies.

The number of words in the fictitious site’s agreements should have required an average of between 40 and 50 minutes to read, whereas the participants spent on average only 51 seconds. The researchers embedded provisions in the agreements that allowed user data sharing with employers as well as the U.S. government’s National Security Agency, and also bound the user to provide a first-born child as payment for access, to which over 90% of users agreed.

Understanding the legal wording of user agreements and privacy policies can require a significant effort for the average person. Image by Наталия Когут on Pixabay.

Although it’s five years old, a 2019 Pew Research Center study of U.S. adults provides some sobering statistics about users’ understanding of the agreements they’re binding themselves to. Many would agree these survey results still apply with little, if any, improvement.

The Pew study indicates that 32% of respondents agree to terms and conditions of a privacy policy about once weekly, 24% once monthly, and 97% have at some point agreed to a privacy policy. Only 9% said they always read a privacy policy before agreeing, 13% do so often, 38% sometimes do, and more than a third never read a privacy policy before agreeing. Among those who read the policies, only 22% reported reading the entire policy before agreement. Younger people and those with lower incomes are less likely to read privacy policies than older, higher-income individuals.

The fact, for most people, is that even though they have the choice to read or agree, the agreements are often very long, often don’t highlight key provisions and waivers of rights, and are worded beyond the average person’s comprehension.

It is commonly understood that the average person reads at a rate of approximately 200 words per minute, although reading of a technical document would be slower. There are, for instance, 8,443 words in Google’s terms of service and privacy policy for Canadian users which, containing technical terminology, would require a minimum of 42 minutes but more likely well over an hour to read and comprehend. Periodic updates could require as much time to review.

Overlooking terms of use and privacy policies can have serious consequences for consumers, and It’s especially important that consumers understand when they are waiving their rights.

Consider the ongoing case of a woman with a severe nut and dairy allergy who ate at a restaurant in the Disney Springs shopping complex in Orlando, Florida in October 2023. The shopping complex is owned by Walt Disney Co., and the woman and her husband chose to eat at the restaurant because both it and Disney, the mall’s owner, “advertised that it made accommodating people with food allergies a top priority,” according to Reuters.

In spite of assurances from wait staff that her food would contain no allergens, the woman died from anaphylaxis triggered by nuts and dairy in her meal, according to a wrongful death suit filed by her husband against Walt Disney Co.

In spite of assurances from wait staff that her food would contain no allergens, the woman died from anaphylaxis triggered by nuts and dairy in her meal, according to a wrongful death suit filed by her husband against Walt Disney Co.

The company initially denied liability on the basis that it was only the restaurant’s landlord, not the owner. The company later changed its defence, stating that the widower’s user agreement with its Disney+ video streaming service, as well as his use of Disney’s website to buy admission tickets to its theme park, contained his consent that any actions against the company would be settled by arbitration and not the courts.

Like many users, the man whose wife died claims that he had no knowledge of such legal provisions or that they could extend, beyond video streaming and theme park admission, to a restaurant meal. After much unfavourable publicity, this August the company relented and agreed that the matter could proceed to court. Josh D’Amaro, chairman of Disney Experiences, told Reuters, “We believe this situation warrants a sensitive approach to expedite a resolution for the family who have experienced such a painful loss,” adding that, “As such, we’ve decided to waive our right to arbitration and have the matter proceed in court.”

Another case involving a waiver of rights involves Uber. Most people know Uber as a company that provides a taxi-like ride-sharing service with an easy-to-use phone app to hail rides. Uber, however, describes itself as “a tech company that connects the physical and digital worlds to help make movement happen at the tap of a button.”

In February 2023, a couple in New Jersey sued Uber for life-altering injuries sustained in a car crash while using Uber’s ride-sharing service. Uber’s defence, which was upheld this October by an appeals court, was that the plaintiff’s use of the Uber-owned Uber Eats food-delivery service contained a contractual provision waiving the right to seek damages from a court and instead to submit to arbitration. The plaintiffs counter-argued that the last time their Uber Eats account was used was by their daughter, who had no knowledge of the arbitration provision.

Unlike Disney, Uber didn’t back down when confronted by a claim that a customer was unaware of a legal provision in a contract for an unrelated service.

Image by Peggy Marco, on Pixabay .

Overlooking privacy and data usage terms can provide major benefits to companies.

When they logged in on October 11, 2024, users of LinkedIn, the social media platform owned by Microsoft, were greeted with a message and link for an “update” to LinkedIn’s terms of use. Clicking on the update link took users to a very lengthy page that was more than a dozen screens of small type to read and did not at the outset provide a clear and concise summary of the changes.

LinkedIn is owned by Microsoft, which is the largest investor in OpenAI, which is the developer of ChatGPT. Logo from Wikipedia .

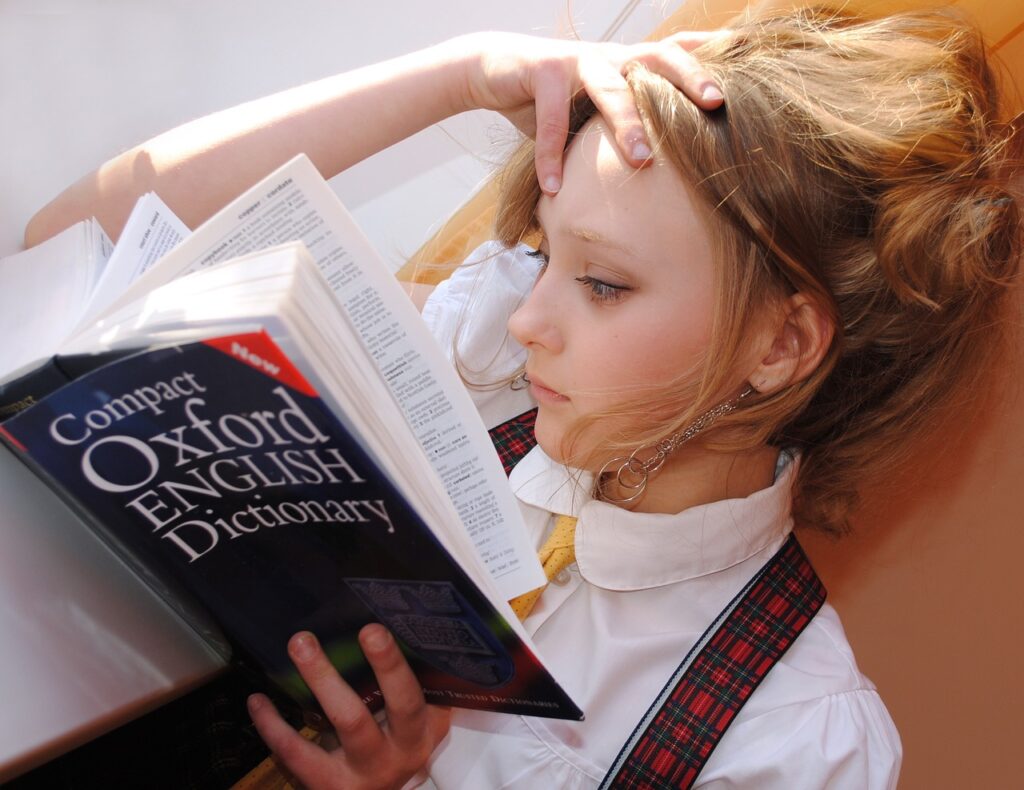

LinkedIn users concerned about the use of their data for training large language model ChatGPT, which is a product of OpenAI, whose major investor and exclusive data partner is Microsoft, might have taken the time to locate privacy settings for their LinkedIn account. There, they would have found the setting shown below with its default set to “On.” Most users would not have been aware of this setting and default, which is very much to the advantage of Microsoft and OpenAI’s commercial interests but of no measurable benefit to the user.

The company’s default setting provided it with free training access to user data.

After this writer and others called attention to the setting in LinkedIn postings, two days later, on October 13, LinkedIn e-mailed users to advise that, “At this time, we are not enabling training for generative AI on member data from the European Economic Area, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. For those outside these regions, we’ve proactively made available an opt-out setting for any members who choose not to make this information available for this purpose.” The e-mail included a link for the privacy setting.

Increased consumer protection in the European Union may provide some benefit to users elsewhere in the world.

Many website users will have noticed that until sometime around the end of 2023 and beginning of 2024, websites rarely offered consumers the opportunity to opt out of third-party cookies. Stronger regulations enacted for citizens of the European Union, and the fact that it’s more cumbersome for global companies to ensure users in one area are treated differently, have led to a welcome change for consumer choice.

Cookies are records of our activities that are placed by websites on our computers. Third-party cookies are of particular concern for privacy because they provide parties unknown to the user but affiliated with the website to track online activities for an extended time across multiple sites. Since the EU’s AI Act requires websites to provide European consumers with an opportunity to opt out of specific cookies, it has become common for sites to offer the same opportunity to people living outside the EU as well.

The European Parliament establishes legislation for the European Union, like the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act. Image: European Union https://european-union.europa.eu/index_en

The EU’s Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act enables European consumers to easily report illegal content, goods, or services on digital platforms and to challenge the content moderation practices of large platforms in particular. The Act also requires transparency on the operation of recommendation algorithms. It remains to be seen whether the large platforms will offer similar rights to consumers in the lucrative North American market and elsewhere in the world.

Legislators in other jurisdictions are beginning to take note and action. For example, the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, introduced legislation in 2023 that includes, among other provisions, “Prohibiting unfair business practices such as taking advantage of a consumer’s inability to understand language in a contract,” and “Limiting when businesses can make one-sided contract amendments, renewals, and extensions without express consumer consent.”

The online user faces many challenges with legal agreements.

The average user is confronted by a number of challenges with the myriads of user agreements that are required. In addition to the length and often impenetrable language of agreements, there are other barriers to consumers that include:

- No standards for format and content: Contracts are seldom alike in the ordering of their provisions or their wording, even in cases when the meaning of the words in different contracts is effectively the same. Further, contracts are written according to the laws of different jurisdictions, which would require some knowledge of international law for a user in one jurisdiction to understand the implications of contractual terms under the laws of a different jurisdiction.

- Differences in user demographics: Lacking experience, some users are less likely to be aware of an agreement’s implications. Lack of experience could be the result of many factors, including the user’s age, language differences, and frequency of accessing online applications. Many regions of the world, for example, lack reliable and affordable internet access.

- Absence of clear summaries for key terms: The European Union is at the forefront of a movement to increase consumer understanding of key contractual provisions, however in many other jurisdictions, including North America, there is no requirement that important terms such as privacy provisions and waivers of rights be highlighted briefly and in plain language at the outset of lengthy contracts.

Image by Mohamed Hassan, on Pixabay

Although companies that write user agreements and privacy policies have more power than the individual user, courts attempt to provide some balance.

Contracts for access to a service, such as a software application, that provide the user no ability to negotiate the contractual terms are called “contracts of adhesion.” Since the service provider has the greater power in drafting such agreements, in some jurisdictions the courts tend to interpret the terms narrowly and, where there is ambiguity, against the party seeking to enforce the letter of the contract.

Even if they uphold the majority of provisions in a contract of adhesion, courts can override particular sections or provisions judged to be unconscionable, extremely unfair, or deliberately ambiguous. For example, a court could strike specific terms that overreach the purpose of the contract, or contain provisions that a reasonable person wouldn’t expect, or are written so as to be beyond the understanding of regular people.

Similarly, if a service provider includes a disclaimer of liability in a contract, courts are less likely to enforce the provision if it’s especially broad or it hasn’t been drawn to the attention of the user. Where there is a significant imbalance of power between contracting parties, such as a large corporation on the one hand and a single individual on the other, some courts have also been known to look more favourably on the claims of the less powerful party.

In some countries, however, and notably in the United States, contracts of adhesion can restrict the hearing of user’s claims to a specific judicial district that’s more likely to rule favourably for the service provider in disputes.

“Forum shopping is a colloquial term for the practice of litigants taking actions to have their legal case heard in the court they believe is most likely to provide a favorable judgment. Some jurisdictions have, for example, become known as “plaintiff-friendly” and thus have attracted plaintiffs to file new cases there, even if there is little or no connection between the legal issues and the jurisdiction.” (Wikipedia)

For instance, Elon Musk’s social media platform X recently changed its contracts so that effective November 15, 2024 users will be required to lodge any complaints with the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas. The Washington Post reported on the curious nature of this change given that X is headquartered in a different district in Texas, and since most large tech companies are based in California the norm is for user contracts to specify a California district where the judges have developed expertise in tech contract laws.

The Washington Post quoted Georgetown University law professor Steve Vladeck, who accused X of “quintessential forum shopping” with the November 15 user agreement change. Vladeck noted that since the 10 of the 11 judges in the Texas Northern District were appointed by a conservative president, there is a greater likelihood of a ruling against an individual plaintiff.

The Washington Post quoted Georgetown University law professor Steve Vladeck, who accused X of “quintessential forum shopping” with the November 15 user agreement change. Vladeck noted that since the 10 of the 11 judges in the Texas Northern District were appointed by a conservative president, there is a greater likelihood of a ruling against an individual plaintiff.

When average X users consent to submit any claims to the Texas Northern District courts beginning November 15, are they aware of the potential effects on their rights and outcomes of actions against X? If they want to continue using the social media platform, they will have no choice but to accept the terms in the contract of adhesion.

Laws can quickly become obsolete with rapid technological changes. Should websites hosting third-party content continue to enjoy legal immunity for harmful content?

Amended nearly three decades ago by the United States’ Communications Decency of 1996, Section 230 of the Communication Act of 1934 provides near-immunity to websites that host third-party content. The amendment’s 26 words have allowed social media platforms to expand with global reach and massive profits, and in a June 2020 review of the law the U.S. Department of Justice concluded that “the time is ripe to realign the scope of Section 230 with the realities of the modern internet.”

“No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” – Section 230

The Section 230 amendment of 1996 provides legal protection to sites like Facebook from responsibility for harmful content posted by its 2.11 billion active daily users. Last year, Meta, which is the owner of social media sites Facebook and Instagram, reported a profit of $39 billion. Without Section 230 protection, it’s likely that Meta would incur significantly greater costs to moderate profit-generating content.

Not only does content moderation introduce a measure of liability for a platform, it’s also expensive to implement and maintain. For example, after firing the majority of its human content moderators, social media platform X has largely automated content moderation. X’s September 2024 transparency report indicated that only 2,361 accounts had been suspended for hateful conduct in the reporting period compared to 104,565 accounts suspended in the second half of 2021, before the platform was taken over by Elon Musk.

As the Department of Justice confirms, Section 230 leaves internet platforms “free to moderate content with little transparency or accountability.”

Alan Z. Rozenshtein of the non-profit Brookings Institution wrote last year that Section 230 “has enabled the business models of the technology giants that dominate the digital public sphere. Whether one champions it as the ‘Magna Carta of the internet’ or vilifies it as the ‘law that ruined the internet,’ there is no doubting that the statute ‘made Silicon Valley.’”

Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. Image: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

The 26 words of Section 230 have been broadly interpreted by U.S. courts to extend to recommendation algorithms of sites like Google-owned YouTube. For instance, in the case Gonzalez v. Google LLC, the family of Nohemi Gonzalez, an American who was one of 130 killed in ISIS-coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, alleged that YouTube’s recommendation algorithms promoted ISIS and provided financial benefits to the terrorist organization.

The Supreme Court refused to hear the Gonzalez family’s case on the basis of Section 230, and as Justice Kagan observed during oral arguments in the case, “Everyone is trying their best to figure out how [Section 230] . . . , which was a pre-algorithm statute[,] applies in a post-algorithm world.”

Enacted in 1996 when recommendation algorithms didn’t exist, Section 230 illustrates a fundamental problem with laws in our fast-evolving technological era. Laws simply can’t keep pace with innovations.

What’s the path forward for consumers?

At a time when economic issues tend to predominate in elections, legal protections for online consumers and updating of laws written for the pre-internet era receive little political discussion. Many political candidates, as well as courts, are often not well-versed in the rapidly changing technological landscape, further adding to the absence of discussion. Many large technology companies looking to boost profits naturally aim to meet the minimum requirements, because the shorter-term costs of increasing consumer protection would drag down the bottom line.

Knowledge of rapid technological changes requires constant updating. Image by Alexandra Koch of Pixabay .

In the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on Gonzalez v. Google LLC, Brookings Institution writer Alan Z. Rozenshtein quoted the words of the judges and observed that “multiple justices expressed uncertainty, even bewilderment, over how to apply Section 230 to this core issue: Justice Thomas was ‘confused,’ Justice Jackson was ‘thoroughly confused,’ and Justice Alito was ‘completely confused.’ Justice Kagan, in the most memorable portion of argument, quipped, ‘We really don’t know about these things. You know, these are not like the nine greatest experts on the Internet.’”

Bolstering consumer protection and rights would seem to require increasing the technological knowledge of legislators and judges, and ensuring it remains current. More legal cases challenging large companies like Disney, Uber, X, and Google over contractual provisions could also help to put the spotlight on the issues. Consumers can also support and seek help from consumer rights advocacy groups.

In our October 2023 editorial Knowledge is Power: Two Changes to Data Privacy to Protect the Value of Human Data, The Quantum Record called for two key regulatory changes for better consumer protection. One is that regulations should require important privacy consents to be clearly highlighted for users, with no defaults, so that users must specifically choose from among the options. The other was for the creation of an international standard framework for privacy policies so that users can become accustomed to a standard form of presentation and be more likely to understand contractual provisions written for a variety of different jurisdictions.

Perhaps changes such as these and those recently enacted by the European Union would help prevent users from blindly agreeing to provisions as humorous and outrageous as in the 2020 experiment by Obard and Oeldorf-Hirsch. They could also provide better guidance to judges and form a more solid framework for future legislators to build on to improve the integrity of legal agreements and consumer protection.

Your feedback helps us shape The Quantum Record just for you. Share your thoughts in our quick, 2-minute survey!

☞ Click here to complete our 2-minute survey