Which image is real and which is fake? Images are real (top row) and synthetic (bottom row). Image attributions (top row left to right): Jay Dixit (cropped); Red Carpet Report on Mingle Media TV (cropped); Dominick D (cropped); Toglenn (cropped). Photographs are from Wikimedia Commons (2025), as published in AI-generated images of familiar faces are indistinguishable from real photographs.

By James Myers

With AI-powered generators like ChatGPT now able to create images and videos that appear nearly life-like, identifying increasing amounts of fake online content is extremely difficult and sometimes impossible for many viewers. Recent research by video-editing company Kapwing indicates that fakes comprise a significant one-fifth to one-third of the videos that are recommended by YouTube’s algorithms to users who don’t have a viewing history.

Although many AI-generated images are made only for entertainment, online fakes can be particularly damaging when their falsehoods are used for disparaging political opponents, blackmail and extortion, and other methods of deception that now include fake online influencers and profiting by tricking algorithmic recommendations.

In its Slop Report, Kapwing explains that it identified 100 trending YouTube channels in every country and used an online tool to determine the number of views, subscribers, and annual revenue for each channel. The company created a new YouTube account “to record the number of AI slop and brainrot videos among the first 500 YouTube Shorts we cycled through to get an idea of the new-user experience.”

Kapwing defines AI slop and brainrot videos as those that are primarily AI-generated with the aim of grabbing the viewer’s attention. In 2024, Oxford University Press named “Brain rot” the word of the year, defining it as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”

Kapwing’s research found that brainrot videos make up one-third of the first 500 short videos that YouTube serves up when its algorithms don’t have a record of a viewer’s preferences. According to Kapwing’s Slop Report, AI slop channels in Spain have attracted the highest number of subscribers, a combined 20.22 million, and the AI slop channel with the highest number of views is in India where it generates an estimated $4.25 million in annual revenues for its sponsor.

Revenue from high viewership numbers is also generated by online influencers, who promote commercial products and earn significant amounts of money by placing creative and well-produced videos on YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and other platforms. Fake AI-generated influencers are beginning to spread virally online, increasingly dominating social media feeds and fooling watchers into thinking they are watching a human.

Since fake influencer videos are relatively inexpensive and far less time-consuming to create, they are rapidly proliferating. In its recent article on the surge in fake AI influencers, the BBC interviewed popular influencer Kaaviya Sambasivam who has a total of about 1.5 million followers on various platforms. Commenting on the ease with which fake online influencing is spreading, Sambasivam said, “It bears the question: is this going to be something that we can out compete? Because I am a human. My output is limited. There are months where I will be down in the dumps, and I’ll post just the bare minimum. I can’t compete with robots.”

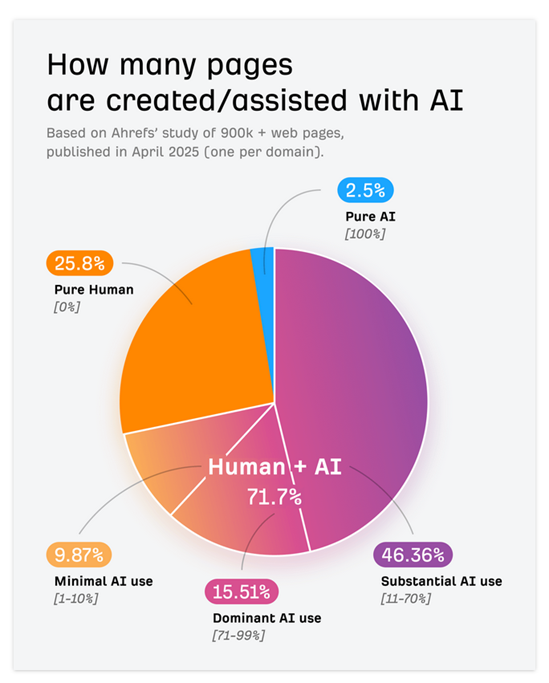

Chart from online marketing platform company Ahrefs .

In April 2025, online marketing platform company Ahrefs analyzed 900,000 newly-created web pages and found that almost three-quarters contained AI-generated content, with a particular prevalence in blog posts. The company notes that “Free, fast AI content generation is available natively in Google Docs, in Gmail, in LinkedIn. AI can summarize Slack messages, conduct article research, shorten transcripts. It’s actively difficult to avoid the big, shiny ‘generate’ button, and will only become more difficult as generative AI becomes further embedded in applications.” Ahrefs further notes that the rate of AI’s online spread will accelerate as new content references AI-generated content already online.

AI applications like ChatGPT that rely increasingly on machine-generated inputs, and less on content produced by humans, risk the complete loss of generating capacity. The Quantum Record’s April 2025 article Cleaning the Mirror: Increasing Concerns Over Data Quality, Distortion, and Decision-Making reported on the finding of a 2024 study by Ilia Shumailov and co-authors that AI training on AI-generated content results in “model collapse,” when generative AI becomes caught in a feedback loop and incapable of generating anything new. Moreover, as online AI content comprises an ever-larger proportion of machine learning data, the reliability of outputs used for important functions like medicine and scientific research will degrade further.

Technology for detecting AI-generated content is improving but is not fully reliable.

In the absence of regulations and controls for watermarking AI-generated content, there are a number of commercially marketed approaches for detecting content created by AI. Although they are improving, the detectors aren’t viewed as generally reliable because of their rate of false positives and false negatives.

A detector for AI-generated text might use algorithms that analyze the statistical features of word combinations, looking for higher variability in the structure of human-written sentences compared to the consistently average form of sentences generated by AI. Another approach, which requires a larger investment of time and resources, is the use of machine learning for training a detector on large volumes of AI-generated and human-written text in order to identify more differences in their patterns.

A study published in August 2025 entitled Can we trust academic AI detective? Accuracy and limitations of AI-output detectors, by Gökberk Erol and co-authors, compared the results of three AI-output detectors on 250 human-written articles and 750 AI-generated texts. The study concluded that “AI-output detectors exhibit moderate to high success in distinguishing AI-generated texts, but false positives pose risks to researchers.”

Another study, entitled Accuracy and Reliability of AI-Generated Text Detection Tools: A Literature Review and published in February 2025, concluded differently. Based on their review of the published results of 34 studies, the authors state that “It is generally proven that AIGT [AI-generated text] detectors are unreliable. This is not to say that the detectors fail at their purpose almost every single time, but it has not reached a level in which faith can be put in the results provided by these detectors.” They note that AI detectors can be particularly incorrect and biased in spotting English text written by people lacking fluency in the language.

Deception in AI-generated images: can we spot the real humans and the fakes?

Although AI image generators aren’t perfect and fake images can sometimes be detected by out-of-place or missing items in a scene, the technology’s rapid improvements are making it very difficult to distinguish between fake and real people in images where only faces are shown.

One pair of images from the site Which Face is Real? Which of the two would you pick to be the photo of a real person and which would you pick to be an AI-generated fake? At first glance, both are plausibly real, but would you be surprised to learn that the one on the right is the fake?

The website Which Face is Real? presents a succession of two images of people, and for each pair challenges the viewer to identify the real person. The site was developed by Jevin West and Carl Bergstrom at the University of Washington, who are co-authors of the 2021 book Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World. Continued technological improvements since the book’s release have made it even more difficult to spot real people in images.

In October 2025, the journal Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications published a study by Robin S.S. Kramer and co-authors entitled AI-generated images of familiar faces are indistinguishable from real photographs, for which the researchers conducted four experiments. For the first experiment, they recruited 110 participants from U.S., Canada, the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand with a median age of 41 years almost equally split between women and men, who were tasked with selecting between real and fake images. The experiment compared images of everyday people with synthetic images of the same people that were generated with a combination of ChatGPT and DALL-E, while the second experiment compared real images of well-known celebrities with fakes.

In the first experiment, only 40% of participants correctly selected 25 of the 96 real images. The same real images had been used in a different study three years earlier, allowing the researchers to compare outcomes and conclude that “these results provide evidence that our participants, while performing poorly on the task, were not simply responding at random.”

The images in the top row are real, while the images in the second row are AI-generated. In the study by Robin S.S. Kramer and co-authors, 96 real and 96 fake images were presented one at a time in random order, and participants were each asked whether the image was real or fake. Images from Fig. 1 of AI-generated images of familiar faces are indistinguishable from real photographs.

The second experiment, using 100 real and 100 fake images of celebrities, was conducted with 115 participants with a median age of 44 years and nearly equally divided between women and men. To create the synthetic images, the researchers prompted the AI to replicate all details of the real image but to change the celebrity’s pose, and all images were cropped to show only the face, neck and, in a few instances, shoulders. The experimental process was similar to the first, but participants in the second experiment were given the celebrity’s name and were also asked to rate their familiarity with the celebrity on a scale of 1 to 7.

When participants were presented with only one celebrity image, about half correctly identified about 10 of the 100 real images.

The third experiment was conducted with 127 participants with a median age of 40 years, close to 60% of whom were men. That experiment again presented 100 celebrity images, this time in sets of three for each celebrity in which two images were real and one was fake. Participants were told that each set contained two real images and were asked whether the middle of the three images was real or computer-generated. The researchers observed “a definite increase in accuracy with the addition of two real photographs.”

The fourth experiment replicated the third, except that the 129 participants (with a median age of 39 years, 58% of whom were men) were not told whether each set of three images contained any real images and were asked instead whether they thought any of the images were computer-generated. The result, with participants accurately identifying fakes about 50% of the time for only 20 of the images, was better than the second experiment, “demonstrating that the presence of additional images, even when it is unclear as to which (if any) are synthetic, may still benefit performance.”

The ease of creating convincing fakes raises the urgency for developing reliable detection methods.

From all four experiments, the researchers “found that familiarity with identities was associated with only modest increases in performance across our tasks.” They note better results obtained for other studies in which people were asked to identify deepfake videos were likely due to clues such as problems with audio and motion synchronization that aren’t available in static images. The study concludes that “New methods of detection should be explored as a matter of urgency since the latest ‘off the shelf’ AI tools can now generate face images of real people that are essentially undetectable as synthetic to most human observers.”

Even though deepfake videos are sometimes easier to detect, they can still be extremely convincing and cause significant loss when used for criminal purposes. As we noted in our August 2025 feature Rise of Virtual Reality Tech Increases Risks of Entering AI’s Third Dimension, and the Need for Immersive Rights, in early 2024 a finance professional at a multinational firm was conned into transferring $25.6 million to fraudsters after participating in an online meeting with what he thought were human staff but were in fact AI fabrications. With rapid advancements in virtual reality technology’s ability to imitate humans, the risk of fraud, blackmail, and extortion will increase while regulations and controls lag far behind.

Whether AI is used to generate text, static images, or videos, there are mounting risks not only for losses from deception and impersonation but also for the collapse of AI generators themselves as they consume more of their own outputs. As attractive as the short-term profits are, with such potential future damage to companies making AI generators and to their human users, it would seem to be in everyone’s interest to rein in the uncontrolled use of increasingly powerful generative technology.

Want to learn more? Here are some TQR articles we think you’ll enjoy:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Can Science Break Free from Paywalls? Technologies for Open Science Are Transforming Academic Publishing

- COP-30 in Belém: What Emerging Technologies Can and Can’t Deliver for Planetary Health

- The Science of the Paranormal: Could New Technologies Help Resolve Some of the Oldest Questions in Parapsychology?

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies

Have we made any errors? Please contact us at info@thequantumrecord.com so we can learn more and correct any unintended publication errors. Additionally, if you are an expert on this subject and would like to contribute to future content, please contact us. Our goal is to engage an ever-growing community of researchers to communicate—and reflect—on scientific and technological developments worldwide in plain language.