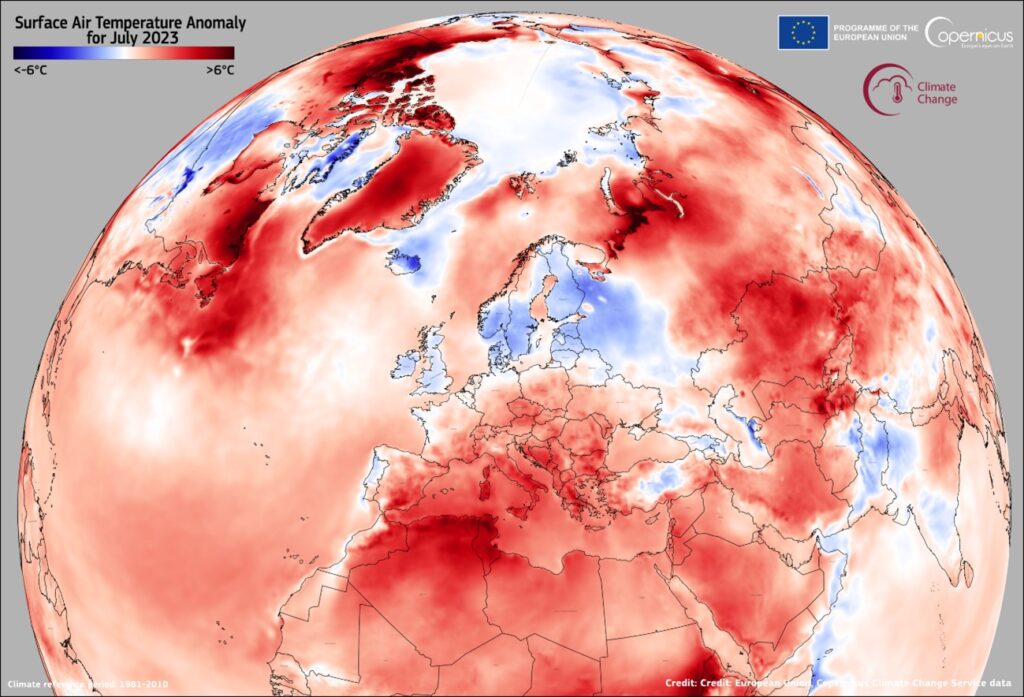

“This visualization, based on data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service, shows the surface air temperature anomaly for July 2023 in Europe, the warmest July ever recorded. Numerous regions in the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in southern Europe, went through severe heatwaves.” European Union, Copernicus Climate Change Service data

By Sambit Mishra and Mariana Meneses

The United Nations’ 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) environmental summit was held in the United Arab Emirates from November 30 to December 12, 2023.

The conference is a diplomatic effort to address the significant global issue of climate change.

The approaches we take for climate change mitigation will play a major role in the years to come.

The annual conference is organized by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and was attended by all 198 member nations. This includes major global superpowers such as the U.S., India, and China, as well as smaller countries such as Luxembourg, Monaco, and Cyprus.

The UNFCCC has been responsible for several climate action treaties, including the Convention Agreement of 1992 (signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and popularly known as the ‘Earth Summit’), the Kyoto Protocol (1997), and the Paris Agreement (2015).

The past COP agreements have marked several key accomplishments in the global efforts to address climate change, such as:

- COP 15, Copenhagen, 2009: Acknowledged climate change as a paramount contemporary challenge, emphasizing the imperative to limit temperature increases to below 2°C, yet the resulting document lacked legal enforceability and did not include binding commitments for reducing CO2 emissions.

- COP 16, Cancun 2010: The Cancun Agreements formalized prior commitments from Copenhagen, and the summit resulted in the adoption of an agreement by the states’ parties, calling for the establishment of a substantial “Green Climate Fund” and a “Climate Technology Centre” and network.

- COP 17, Durban, 2011: The conference reached an agreement in 2015 to establish a legally binding deal involving all countries, set to take effect in 2020, and made strides in creating a Green Climate Fund, while securing commitments from all nations, including the U.S. and emerging countries (Brazil, China, India, and South Africa).

- COP 18, Doha, 2012: The outcomes included the continuation of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol with a second commitment period, although with reduced ambition and participation, limited progress on financial commitments from developed countries for 2013-2020, and the introduction of the concept of “loss and damage” as a potential avenue for compensation to vulnerable communities affected by climate change.

Since COP18, the concept of “loss and damage” – i.e., the idea to compensate vulnerable communities affected by climate change – has been debated and has also evolved, as negotiations progressed in the following conferences. In December 2023, COP28 was expected to negotiate the implementation of such compensation mechanisms.

Compensation Mechanisms are, essentially, a means of “Damage Control.”

Within the realm of climate change, they encompass a range of strategies and policies designed to offer financial assistance to individuals, communities, and nations affected by the repercussions of climate change. These include liability rules that define legal responsibility for climate-induced damages and the subsequent compensation process. Additionally, compensation can be provided through ex post ad hoc government initiatives, government-financed compensation funds, first-party insurance for disasters purchased by individuals or entities, and government intervention as a reinsurer of last resort when private insurers are unable or unwilling to participate.

The overarching goal of these mechanisms is to ensure that those disproportionately affected by climate change, often the most vulnerable and least culpable for its origins, receive necessary financial support for recovery and adaptation. However, their implementation and effectiveness are subject to considerable variation, contingent on factors such as legal frameworks, economic conditions, and political contexts across different countries.

In another TQR article, we have discussed an exemplary case of how, more often than not, vulnerable communities end up paying the price of environmental damage caused by economic interests of other nations.

Brazil struggled to identify the tanker responsible for the 2019 oil leak that contaminated half of the country’s coast, causing large environmental and economic losses. Thousands of volunteers cleaned the oil-stained beaches. Source: Environment Justice Atlas

☞ Check out TQR article “Clean Technologies and Technologies That Clean: Undoing the Climate Damage We Have Caused”.

So what has happened between COP18 and COP28 about compensating vulnerable communities mostly affected by climate change?

- COP19, Warsaw, 2013: Representatives from less affluent nations left the COP19 negotiations in Warsaw due to a failure to reach consensus on issues related to climate-related losses and damage. Subsequently, a diluted agreement was eventually achieved.

- COP27, Egypt, 2022: COP27 concluded with a breakthrough agreement on loss and damage, establishing a dedicated fund and new funding arrangements to assist vulnerable countries affected by climate disasters, with a transitional committee set to operationalize these measures at COP28.

Finally, what was accomplished at COP28?

A groundbreaking decision was made to establish a Loss and Damage Fund, signaling a potential turning point in global climate policy. However, the historic agreement on the loss and damage fund, seen as a victory for developing nations, fell significantly short of the financial support required.

As The Guardian reports, wealthy countries, which are primarily responsible for the climate crisis, pledged just over $700 million to the loss and damage fund at COP28, constituting less than 0.2% of the estimated annual losses exceeding $400 billion faced by developing countries due to global heating.

Notable pledges include $100 million from the United Arab Emirates (the host country), matched by Germany, and slightly exceeded by Italy and France.

The pledges are considered inadequate by climate experts and activists, who emphasize the interconnectedness of loss and damage, adaptation funding, and emission reduction. Details regarding the nature and timing of the funds remain unclear.

Despite these shortcomings, COP28 was hailed as “the beginning of the end” by a UNFCCC press release, according to which nations are taking substantial steps towards a fossil fuel-free future, showcasing efforts from major contributors like India, the U.S., and China leading in renewable energy system development.

COP28 Official Photo. Source: Fotografía oficial de la Presidencia de Colombia.

So, if they are doing little to compensate the most vulnerable and affected countries, what are these highly polluting countries doing to fight human-induced climate change?

- The United States provided $370 billion for low-carbon technologies under the Inflation Reduction Act (available in this 2023 White House pdf), and The Federal Reserve Board is conducting a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise with six banking organizations, with results are expected to be declared by the end of 2023 (available in this 2023 US Federal Reserve System pdf). The country has five operational carbon markets, and one under discussion in New York, currently covering only 9% of national emissions. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed two policies in 2022, one aimed at corporate climate-risk disclosure and the other one at investors but is facing possible lawsuits unless the text in these policies are weakened.

- China stated in 2020 that it intended to reach its emission peak by 2030 and become carbon neutral as soon as 2060. It is currently providing the largest amount of fossil-fuel support among all the G-20 nations. Around 40% of the total greenhouse gas emissions in China are covered by some form of carbon pricing mechanism, such as a carbon tax or an emissions trading system (available in this OECD pdf). According to Phys.org, China is currently responsible for 27% of global carbon dioxide emissions, and emerged as a key player in COP28 with its efforts to transition away from fossil fuels and lead in renewable energy development, manufacturing the majority of solar panels and wind turbines globally, aiming to replace fossil fuels gradually, significantly reducing coal reliance, and aligning with the U.S. in supporting a global tripling of renewable energy by 2030, marking a potential turning point in climate policy.

- India actively participated in highlighting, during COP28, the need to enhance climate finance accessibility, affordability, and availability for developing nations. According to Reuters, the country has successfully reduced its greenhouse gas emissions rate by 33% over 14 years, outpacing expectations, as renewable energy production increased and forest cover expanded.

Besides controlling carbon emissions, introducing carbon tax schemes, and other regulatory measures, some countries have taken quite unique measures in their approach to climate control.

- Singapore, being densely populated with no room for expansion, found an innovative way to deal with with climate control requirements. Vertical Gardens, Singapore’s Tree house Condominium at District 23, holds the Guinness world record for the world’s largest vertical garden.

- The Netherlands, faced with rising sea levels, is gearing up to turn the problem into a solution. Plans includes floating neighborhoods, green roofs, and adaptable infrastructure to cope with changing climate conditions. Antwerp and Rotterdam are among the cities where this control mechanism has been implemented. Read more about them here.

- Ethiopia has developed a highly scaled-up forestation scheme that aims to plant billions of trees to develop a “Carbon Sink”. In the words of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “The Green Legacy Initiative is a demonstration of Ethiopia’s long-term commitment to a multifaceted response to the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation that encompasses agroforestry, forest sector development, greening and renewal of urban areas, and integrated water and soil resources management.”

- Japan, with little land to develop a solar farm, has decided to use water instead. Floating solar farms have been developed floating that can be expanded significantly in the context of Japan’s power requirement. Given that Japan is geographically a small nation with more water area than land, the solution is particularly innovative. In fact, Japan’s transitions to renewable energy may be the quickest we can expect to see. Read more about Japan’s floating solar farm initiatives here.

Singapore’s 24-storey condominium with a green wall measuring over 24,000 square feet. Image: INHabitat

But what are some of the world’s major polluters doing about this rising problem of the environment?

- The United States, whose climate change action is led by the United States Environment Protection Agency (USEPA), aims to target HFC’s (hydrofluorocarbons), revise emission and fuel use standards for light- and heavy-duty transportation (both on land and in the air), and develop a Renewable Fuel Standard Program and Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program. It indicates a shift in trend to renewable sources of energy.

- India, however, is not blessed with significant amounts of available land. With the world’s densest population, it would be less reasonable to expect solar or wind farms in India. The next best option would be hydrogen fuel, and India is taking it seriously. Its National Green Hydrogen Mission is in full swing, unveiling its first bus and even a train that are both fully hydrogen-powered. Aiming to be energy-independent by 2047 and carbon neutral by 2070, the project appears to be very promising in India’s drive to topple China’s global dominance in the clean energy sector.

- China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gasses, has been hit hard by climate change. 2023 saw China ramp up its renewable energy sector at an astounding pace. As reported by CNA, “China is also the world’s largest manufacturer of solar panels and wind turbines. Domestically, it is installing green power at a rate the world has never seen. This year alone, China has built enough solar, wind, hydro and nuclear capacity to cover the entire electricity consumption of France. Next year, we may see something even more remarkable – the population giant’s first ever drop in emissions from the power sector.”

After COP28’s conclusion, the world waits to see whether this multinational summit will achieve its purpose. As the world, now very visibly, transitions from the polluting fossil fuels to the non-polluting electric technology, the approach of each country to climate change mitigation will certainly play a big role in the years to come, and it can be said that a lot will change between this conference and the next.

Highlights of COP28

[Reference (pdf): Climate Policy Factbook: COP28 Edition by Victoria Cuming and Maia Godemer]

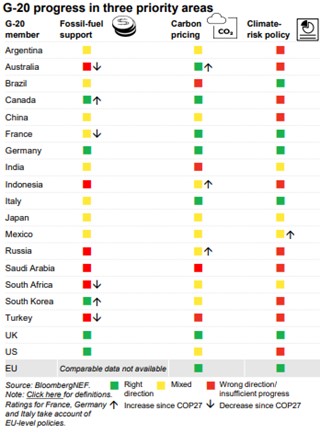

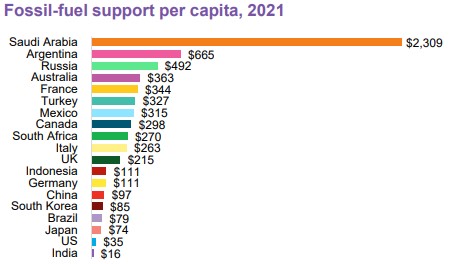

- In total, G-20 governments provided $2.7 trillion in support for coal, gas, oil and fossil-fuel-fired power over 2017-2021: G-20 support for fossil fuels closed at $600 billion in 2021 alone – 14% more than in 2017. But the trends vary significantly across countries: Brazil, India and South Korea have made massive cuts to their fossil-fuel support funds. These changes mean that these countries provide some of the least fossil-fuel support per capita. In contrast, Mexico and Turkey provided three times as much fossil-fuel support in 2021 compared with 2017 levels.

- Developed economies in the G-20 have made more headway in moving away from coal power: On average, the Annex I parties reduced coal-fired generating capacity by 19% relative to 2018. In contrast, non-Annex I parties in the G-20 expanded their capacity by about 8%, while some countries far surpassed this “average”, including Indonesia (33%), China (12%) and Brazil (11%).

- G-20 carbon-pricing policies cover 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions: China’s national market leads the world’s carbon-pricing program in terms of emissions. But, the EU ETS (European Union Emissions Trading System), stands atop china due to high prices and larger trade volumes. Still, its share in the world market is improving: today, 75% of trade volumes pass through the EU ETS, compared to 90% in 2017.

- The rising number of robust climate-risk policies in development indicates these will become the standard: G-20 countries are assessed on their competency in passing or writing laws that create the right regulatory environment to force corporations and financial institutions to assess their exposure to climate risks and drive action to reduce it. Such policies should be gradually implemented to enable organizations to develop the right skills without creating a compliance burden.

Source: Climate Policy Factbook.

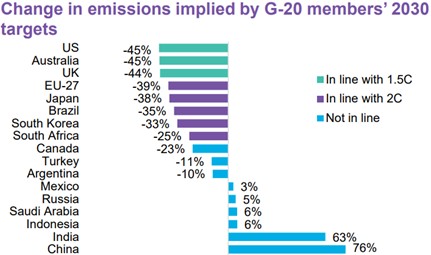

Source: Climate Policy Factbook.

Source: Climate Policy Factbook.

The establishment of COP28’s Loss and Damage Fund, marked by a groundbreaking decision at the climate conference in Dubai, is considered a promising step towards climate justice, aiming to compensate countries facing the impact of climate change; however, questions about its effectiveness and governance under the World Bank, coupled with concerns about the historical underfunding of climate finance mechanisms and the need for innovative financing solutions, emphasize the challenges and call for a comprehensive, transformative approach to sustainable development beyond mere palliatives.

Image generated using Microsoft’s Copilot.

Interested in exploring related topics? Discover these recommended TQR articles:

- Clean Technologies and Technologies That Clean: Undoing the Climate Damage We Have Caused

- Saving the Planet: Nobel Prize Recognizes Climate Science, but Will Mindsets Change in Time to Sustain Nature’s Potential and Value?

- Mega-trees: The Critical Role and Vulnerabilities of Nature’s Giants in Forest Ecosystems and Climate Change Mitigation

- Technology and Mental Wellbeing: Huge Challenges, and the Potential of a Bright Future for the Human Mind

- Financing Climate Change and Abolishing the Obsolete Zero-Cost Assumption for Natural Resources

- Preserving Biodiversity: The Race Against Ecosystem Loss

- Revolutionizing Mobility: Are EVs, Hyperloop and Supersonic flight the future of transportation?