Bronze Age Golden Hat Exhibit, Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany. Image source.

By John Bamford

The Mystery Begins In a Farmer’s Field.

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt, Historical Museum of the Palatinate, Speyer, Germany

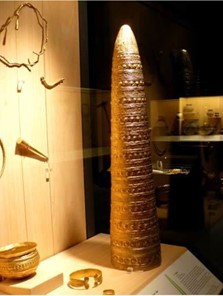

On April 29, 1835 in a farm field about one kilometre north of the village of Schifferstadt in Southwest west Germany, just west of the Rhine River, a farmer named Josef Eckrich uncovered the tip of an object buried just below ground level. He cleared a rectangular pit about 60 centimetres deep and found at the bottom a slab of burnt clay resting on a bed of sand. On top of the slab was a golden conical object with a rounded top. Three bronze axe heads rested against the cone. Inside the cone was a mixture of earth and ash.

The next day Eckrich took the cone to officials in Speyer, on the Rhine River, a short distance from Schifferstadt. He eventually sold the cone for 570 Gulden, of which 120 Gulden were from King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who wanted it in his state collection.

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt was the first discovery of a Golden Hat.

Its manufacture has been dated to between 1400 to 1300 BC, making it the oldest Golden Hat yet found, and, at approximately 30 cm high, it’s also the shortest of the Golden Hats discovered.

The Schifferstadt Golden Hat is made from a single sheet of hammered gold, repeatedly heated and beaten down to thickness of paper, about 0.25 millimetres thick, and then shaped into a cone. The brim is even thinner than the cone. The entire hat is 29.6 cm high, about 18 cm wide at the base, and the brim is about 4.5 cm wide beyond the cone. Originally the hat included a copper wire around the edge of the brim to give it greater mechanical stability, but this was lost. The interior of the hat shows evidence of what could have been a cloth cap lining and a chinstrap to hold it in place.

What could possibly have been the purpose of the Golden Hat, made from one of the most precious metals of time and so carefully and beautifully constructed?

- The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt surrounded by 3 bronze axe heads found resting against it.

- The farm field marker where the Golden Hat of Schifferstadt was discovered.

Ancient Knowledge of Metallurgy Revealed

The hat weighs only about 350 grams. It’s an alloy mostly of gold (85-90%), with a lesser amount of silver (about 10%) and small amounts of copper and tin (less than 1% each). It’s evidence of an advanced understanding of ores, smelting, metals, and metallurgy that was characteristic of the Late Bronze Age (1600 to 1200 BC or later), knowledge that extended from the Near East/Mesopotamian region beginning in the Early Bronze Age from 3500 to 2000 BC.

The predominant Late Bronze Age culture in Central Europe was the Urnfield culture. The name “Urnfield” has been applied due to their custom of cremating the dead and storing the ashes in urns. These urns were often covered with a stone or some sort of bowl. We know that when the Schifferstadt Golden Hat was discovered, it was originally filled with earth and ash, none of which was retained. Could this have included human ashes?

The hat is divided along its entire length into horizontal bands and ornamental symbols following a systematic scheme that used five different types of stamps and a chisel or a liner tool. The ornamental bands consist of mostly circle and disk shapes. They are separated by ring ribs which form bands around the entire circumference of the hat. The entire motif was accomplished by chasing, or embossing, the surface after first filling the cone with some sort of strengthening or support material like wax, tree resin, or pitch that was later removed.

A Second Golden Hat Appeared, Not Far from Poitiers

In 1844, the second Golden Hat was discovered in a field near the village of Avanton, France, about 12 km north of the city of Poitiers. The Avanton Gold Cone was damaged and is missing a brim. The cone is 55 cm heigh, weighs 225 grams, and has been dated to between 1000-900 BC in the Late (or very late) Bronze Age.

Like the Schifferstadt Golden Hat, the Avanton Cone is divided into horizontal bands decorated with concentric circles of varying diameters separated by rib or ring bands. The tip of the cone is decorated with a sun-like starburst, which the Scifferstadt Golden Hat does not display. The cone’s phallic shape originally suggested some sort of fertility symbol, but current understanding suggests a much different purpose.

- The Avanton Gold Cone, Musée d’Archéologie Nationale at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris.

- The tip of the Avanton Gold Cone showing a star-like sunburst.

The Mystery Deepens a Century Later, When Another Hat is Unearthed, Near Nuremburg

The third Golden Hat was discovered in 1953. The Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch was discovered while tree stumps were being cleared in a forested area between the villages of Ezelsdorf and Buch in Southern Germany, southeast of Nuremburg. It was first noticed buried about 8 cm below the surface, but the workers had no idea what it was. They continued their clearing, and in the process broke the cone into several pieces which were then discarded. Later, rain would wash away the debris and reveal the pieces to be gold, and in the 1990s those pieces were recognized as parts of a Golden Hat.

The reconstructed Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch is the tallest Golden Hat discovered to date, at 88 cm heigh, although it might have originally been as short as 72 cm. The hat weighed 330 grams, an estimate that includes the brim which was lost during recovery. Like the other hats or cones, it was manufactured from a single sheet of hammered gold alloy about 0.78 mm thick and consisting of about 88% gold, 11% silver, and less than 1% each of copper and tin.

Its length is divided into 154 horizontal bands and symbol rows by using the repoussé technique (hammering from the inside) and chasing (embossing by hammering from the outside), in much the same way as the Schifferstadt and Avanton examples. The majority of the symbols are concentric circles as well as small horizontal eye-like ovals, miniature eight-spoked wheels, and small cones. Similar to the Avanton Gold Cone, the tip of the Ezelsdorf-Buch Cone is decorated with a sun-like starburst. The entire decoration used 20 different decorative punches, a comb, and what are either cylindrical stamps or decorated wheels.

- The Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buch, German National Museum, Nuremburg, Germany

- Marker at the discovery location of The Golden Cone of Ezelsdorf-Buck, Ezelsdorf-Buch, Germany.

From Either Southern Germany or Switzerland, Another Hat Emerges

The discovery location of the fourth (and so far last) Golden Hat was found is uncertain. It was purchased by the Berlin Museum of Prehistory and Early History in 1996 and, according to the seller, it may have come from a Swiss private collection 1950s or 1960s, as it was first noticed in the international arts trade in 1995. It was probably from southwest Germany (Swabia) or Switzerland, and we have no idea of the original conditions of discovery or of any other artifacts that may have been with it.

This hat is the best preserved and most extensively studied of all the Golden Hats. Like the other Golden Hats, it originates from 1000-800 BC, during the Late Bronze Age.

The good preservation of the cone suggests that, like the Schifferstadt Golden Hat, it must have been carefully filled with soil or ashes and then buried upright in relatively fine soil. As with the Schifferstadt Golden Hat, it was probably filled with material such as tree resin, wax or putty or pitch in order to embellish the hat with ornamental bands and symbols, the same banded pattern seen in the other hats/cones.

It is 75 cm heigh, weighs 490 g and is made from 0.6mm thick sheet of hammered gold alloy containing 88% gold, 10% sliver, and less than 1% each of copper and tin, just as with the other hats discovered.

The cone of the hat is decorated with 21 horizontal bands and rows of symbols along its length. At least 17 separate tools (14 different stamps and 3 decorated wheels or cylindrical stamps) were used. One of the bands is very distinctive with a row of recumbent crescents on top of an eye-shaped symbol. The tip of the cone has a sun-like starburst decoration, similar to the Ezelsdorf-Buch Golden Cone.

At the bottom of the cone, the sheet gold is reinforced by a 10 mm wide ring of sheet bronze. The external edge of the brim is strengthened with a twisted square-sectioned wire, covered with gold leaf that is turned upwards. At the join of the cone shaft and the base is a wide vertically ribbed band. The brim is decorated with similar motifs to the cone.

- The Berlin Gold Hat, in the Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

- Detail of the mid-section and top of the Berlin Gold Hat, the Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

- Detail of the base and brim of the Berlin Gold Hat, the Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

A Tantalizing Enigma: Funeral Rites or Astronomical Calendar?

Only four Golden Hats have been discovered, and none were uncovered in thoroughly studied archaeological excavations. As a result, they lack much meaningful archaeological context, other than some knowledge of the site of the Golden Hat of Schifferstadt.

Considering the conditions and the technical means available at the time, the production of even an undecorated Golden Hat is an immense technical achievement. The know-how, time and effort, and cost of producing these hats would have been considerable. Certainly, a far greater expense and effort was made on the Golden Hats than would be expected for a typical ceremonial piece of headwear.

So why go to that great expense and effort?

The hats may have been made for funeral purposes. We know that the Urnfield culture derives its name from their custom of placing the ashes of their dead in urns which they buried in field pits. Some of these burials were simple, but others were more elaborate, reflecting the social stratification of the culture.

We have evidence, particularly with the Schifferstadt and Berlin Golden Hats, that they once contained ashes. The fact that the Schifferstadt Golden Hat was located in a pit in a field fits well with Urnfield burial customs. The hat rested in an upright position, sitting on a block of burnt clay, underneath which was a layer of sand possibly for drainage and to level the clay block. Resting against the base of the hat were three, evenly-spaced Bronze Age axe heads. The construction of the pit to hold an object of such value, however, suggests this wasn’t an ordinary Urnfield event. And if the ashes inside were actually human, then who was this person and why would their ashes be inside such an expensive burial urn in a field pit custom-made for a Golden Hat? And if the hat was not part of some funeral custom and did not contain human ashes then why bury at all and in this manner? Were they attempting to hide it from potential theft or confiscation? Or was the burying of the hat this way part of some other type of Urnfield ceremony?

Astronomical Time Tracking

We know that sun-cults and sun worship were common in Bronze Age Europe. The Sun, its daily arrival and departure, its meaning in daily life, and its connection to the changing seasons and seasonal agriculture, all made the Sun a source of mystery, wonder and awe. Sun cults were cults of fertility (sometimes masculine and sometimes feminine), associating the sun with new life and new growth.

We know that sun-cults and sun worship were common in Bronze Age Europe. The Sun, its daily arrival and departure, its meaning in daily life, and its connection to the changing seasons and seasonal agriculture, all made the Sun a source of mystery, wonder and awe. Sun cults were cults of fertility (sometimes masculine and sometimes feminine), associating the sun with new life and new growth.

While the sun’s rhythm may have marked the passage of each day, people also needed a means to keep time beyond a single day and night and so they turned to a second light in the sky. The moon was therefore one of our first timepieces, its face changing nightly and with the regularity of the seasons, making it a reliable marker of time. Lunar worship and cults spread across Europe and Asia during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The monthly cycle of the moon was symbolic of life from birth, infancy, adulthood and old age until death.

Someone with knowledge of the patterns and behaviour of the Sun and the Moon, as well as the ability to interpret and predict the practical implications and mystical meanings of these patterns, would be revered. We might call them cult-leaders or priests or wizards. This would have conferred power and authority on them, a status that tribal leaders likely valued. The tall conical Golden Hats are embellished with Sun and Moon symbols, and sometimes with sun-like starburst symbols at the tip, which are very likely intended to convey more than just decoration.

We now interpret the Golden Hats to be the religious objects of leaders, priests, or wizards of a Sun or Sun/Moon cult that was widely followed across Central Europe in the Bronze Age and beyond.

The hats appear to have been worn to demonstrate officium, wisdom, and sacred knowledge.

That the Golden Hats were in fact headwear seems certain: the openings are oval, not round; the shapes and diameters are roughly the same as a human skull; there is evidence of chin straps and soft inner linings; and the reinforced brim would have helped in their handling, placing on the head, and protecting the wearer from both sun and rain. That they were associated with religion and cult is supported by their careful and ritualistic burial.

Knowledge of the Sun and the Moon

And we now also believe that the Golden Hats were probably used as lunisolar calendars.

Detailed study of the Berlin Golden Hat points to the hats having been a means of cryptically documenting celestial knowledge, and the hats could have been used to teach this knowledge to a chosen few. The cryptic, ostentatious, and enormously valuable head-ware would convey authority, wisdom and secret special knowledge that few would have, inspiring reverence.

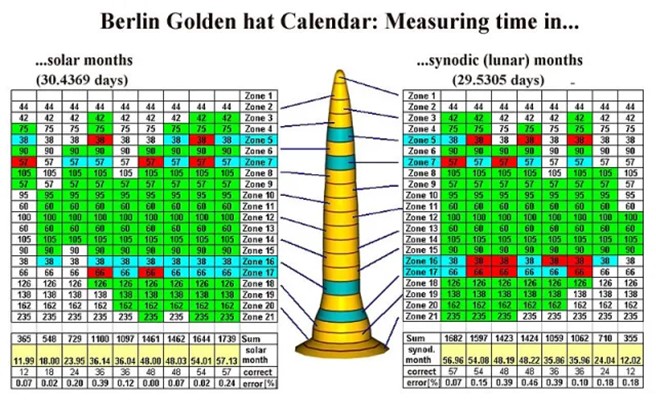

Research by the German Museum of Prehistory and Early History suggests that the 1,739 Sun and half-Moon symbols on the surface of the hat represent the Metonic cycle discovered by Greek astronomer Meton of Athens in 432 BC. This would have allowed the wearers in the Late Bronze Age to calculate and predict the movements of the Sun and Moon, to determine the right time for sowing, planting, and harvesting crops. It would have conveyed very powerful knowledge to predict the cycles of the Moon, the passage of months and years; and the solstices, equinoxes and other lunisolar events.

The illustration above summarizes the research, analysis and lunisolar interpretation of the Berlin Golden Hat. It demonstrates how the bands, or zones, of symbols can be used to measure and predict time in solar and lunar terms. Using this lunisolar calendric interpretation allows a direct reading of time in either lunar or solar dates as well as the conversion between the two.

Consider that potential of the hats, and how it was achieved.

An astronomical and mathematical system was incorporated in the artistic embellishment of a Late Bronze Age object, manufactured 3,000 years ago with knowledge of ores, smelting, metallurgy, technology and craftsmanship, and conveying potential religious, mystical, and practical power. Enormously expensive and time consuming to manufacture, the hats required considerable technical skill and technological know-how preserved by meticulous burial in a location of significance, and possibly containing the ashes of the wearer.

How many more of these are yet to be discovered? What more will they tell us about ourselves and our history and how we got to where we are? So whatever you might be wearing on your head, take your hat off to those people, wonder at their achievements and their legacy to us.

Article header image: Bronze Age Golden Hat Exhibit, Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany

So Many Hats

“Without hats there is no civilization” — Christian Dior

“Wearing a hat confers undeniable authority over those without one” — Tristan Bernard

Ascot, bonnet, fedora, sombrero, baseball caps, beanie, bearskin, deerstalker, dunce, fascinator, beret, toque, wizard, zucchetto — and on and on.

Are you talking through your hat? Eating your hat? Keeping it under your hat?

Whether for function or fun, hats have many purposes: protection against the weather, ceremonial, safety, religion, fashion, authority.

Our heads and faces are the most prominent features that others notice, and where we direct our gaze when we first meet someone. Wearing something on your head is a type of self-affirmation; it reflects your principles, your attitude, your belonging; it displays your origin, your profession, your position; it gives your head and face a different look.

Hats have a certain power.

Hats project meaning. Hats send a message. Hats say something about the people wearing them.