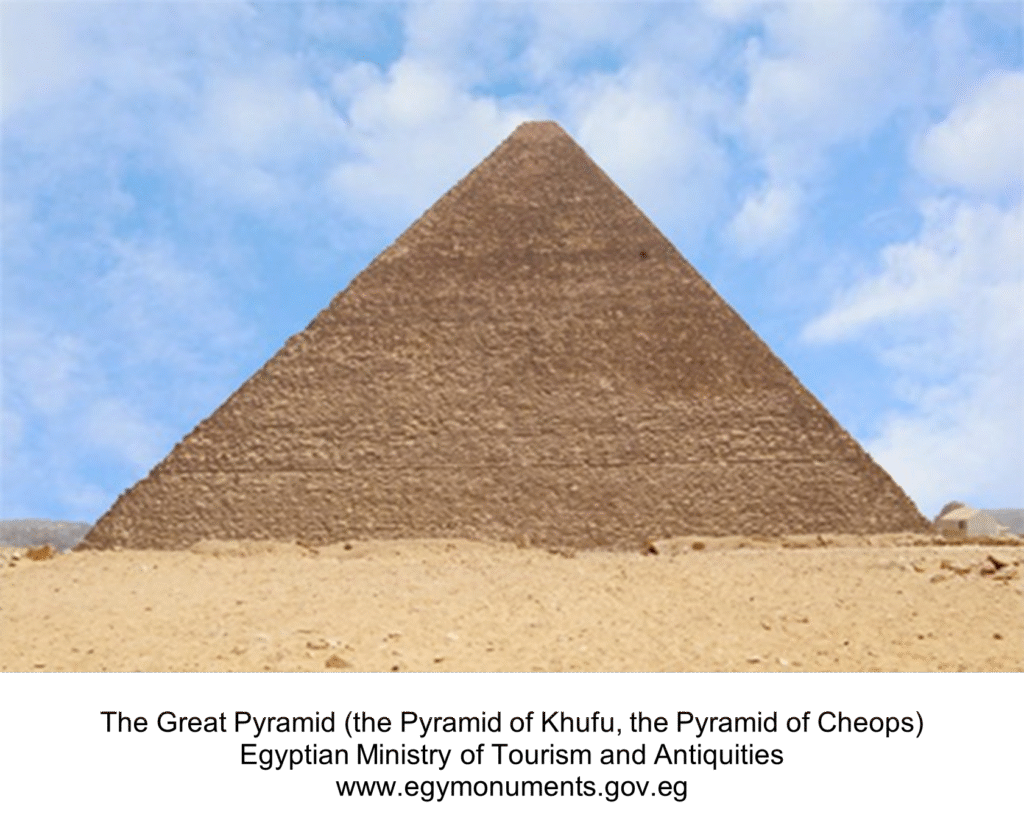

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Image by Douwe C. van der Zee, on Wikipedia.

By John Bamford

“And so Egyptians built a passage to the heavens for the pharaoh, 50 stories of stone rising out of the desert, pointing to the sky.” — Elizabeth Mann (author)

“As for the pyramids, there is nothing to wonder at in them so much as the fact that so many men could be found degraded enough to spend their lives constructing a tomb for some ambitious booby, whom it would have been wiser and manlier to have drowned in the Nile, and then given his body to the dogs.” — Henry David Thoreau (naturalist, poet, and philosopher)

“Virtually any pointed edifice is considered a candidate for alien engineering. After all, how could the Egyptians or Mayans have possibly stacked up stone blocks into pyramids?” — Seth Shostak (Senior Astronomer, SETI Institute)

“”Man fears time, but time fears the pyramids.” — Arab Proverb

In July 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte and his French Army of the Orient readied for battle in their conquest of Egypt some nine miles away from the Great Pyramid of Giza, across the Nile River from Cairo.

Prior to what he called the Battle of the Pyramids on July 21st, Napoleon gave his Order of the Day:

“[We] came to this country to save the inhabitants from barbarism, to bring civilization to the Orient and subtract this beautiful part of the world from the domination of England. From the heights of the Pyramids, forty centuries look down on us.”

“Forty centuries” was not a bad estimate, given that we believe the Great Pyramid was built around 2600 BC, about forty-four centuries before the battle. (How was Napoleon able to come up with such a close approximation in 1798?)

The Battle of the Pyramids. Francois-Louis-Joseph Watteau (1798-1799). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes. wikipedia.org

The French emperor, who spent a night sleeping in the pyramid, was as curious as many still are today about the construction and purpose of the giant structure. Many of the mysteries of his time endure today, but with the help of technology over centuries we’re discovering some answers – and yet more questions.

Here, we’ll trace the exploration history of the Great Pyramid of Giza. We’ll explore the use of technologies through centuries that have led to the use of modern robotics to uncover the mysteries of the curious shafts that pierce the stone block walls and enter two chambers inside the structure. What was the purpose of these shafts?

We’ll analyze a number of the possible explanations, after we take you back in time to consider the approaches taken for centuries to unravel the mystery.

The history of pyramid explorers and the technologies they used is intriguing.

In the end, though things didn’t turn out well for the French conquerors of Egypt. Napoleon’s plans ended with his departure from Egypt in 1799 and the final defeat of his army by British forces in 1801. But during their time in Egypt, the French attempted what they saw as “bringing civilization” to the area, including almost two hundred French scholars, scientists, librarians, archeologists, geographers, and engineers. And so began much of the modern organized study and fascination with ancient Egypt, the pharaohs and their constructions.

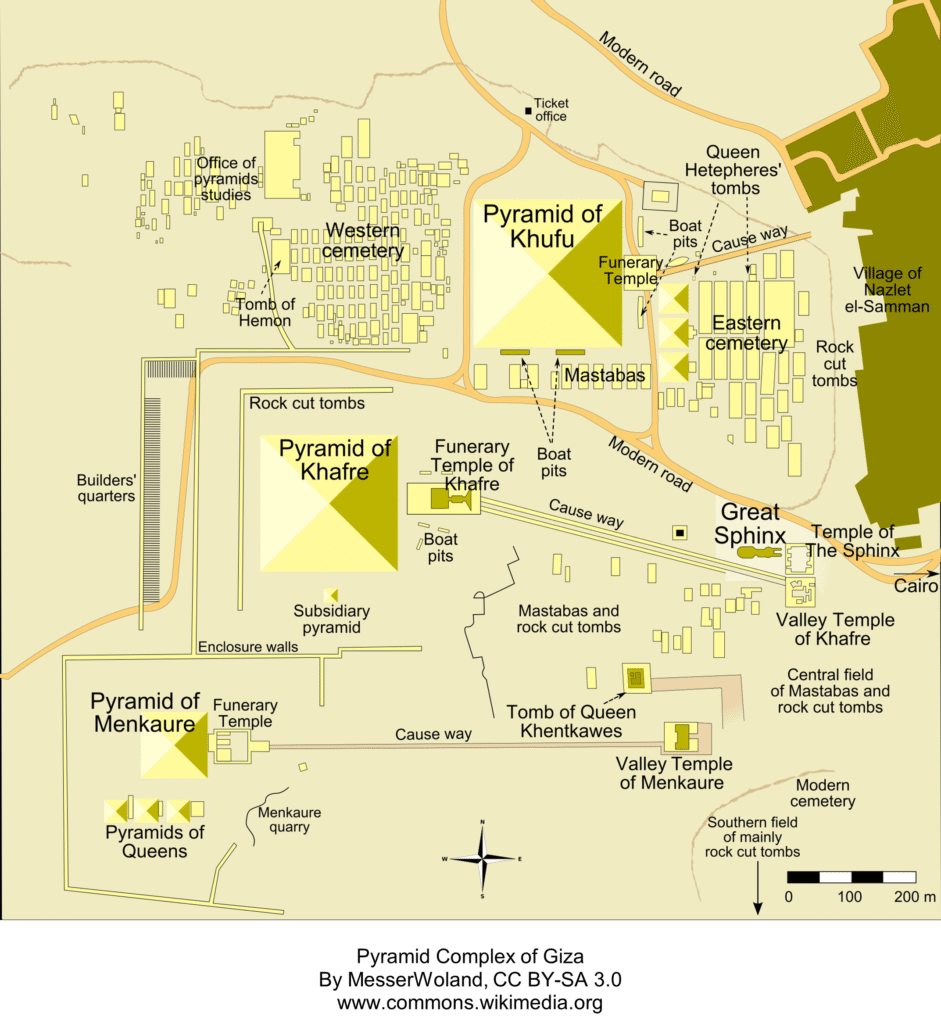

Their fascination included the great necropolis of pharaohs known as the Pyramid Complex of Giza, built on an elevated limestone plateau on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Cairo. The largest pyramid is the “Great Pyramid”, also known as the Pyramid of Pharaoh Khufu or the Pyramid of Pharaoh Cheops (“Cheops” being the Greek interpretation of the Pharaoh’s name).

By locating it on the high end of this natural plateau Khufu ensured that his Great Pyramid, Akhet-Khufu (“horizon of Khufu”), would remain widely visible on the horizon.

From about 2600 BC to 1311 AD, this tomb of the Pharaoh Khufu was the tallest manmade structure known at an original height of 146.6 metres. But in 1311, this height was exceeded by just thirty centimetres with the completion of Lincoln Cathedral at 146.9 metres. (Did the builders of Lincoln Cathedral plan this or was it just a coincidence?)

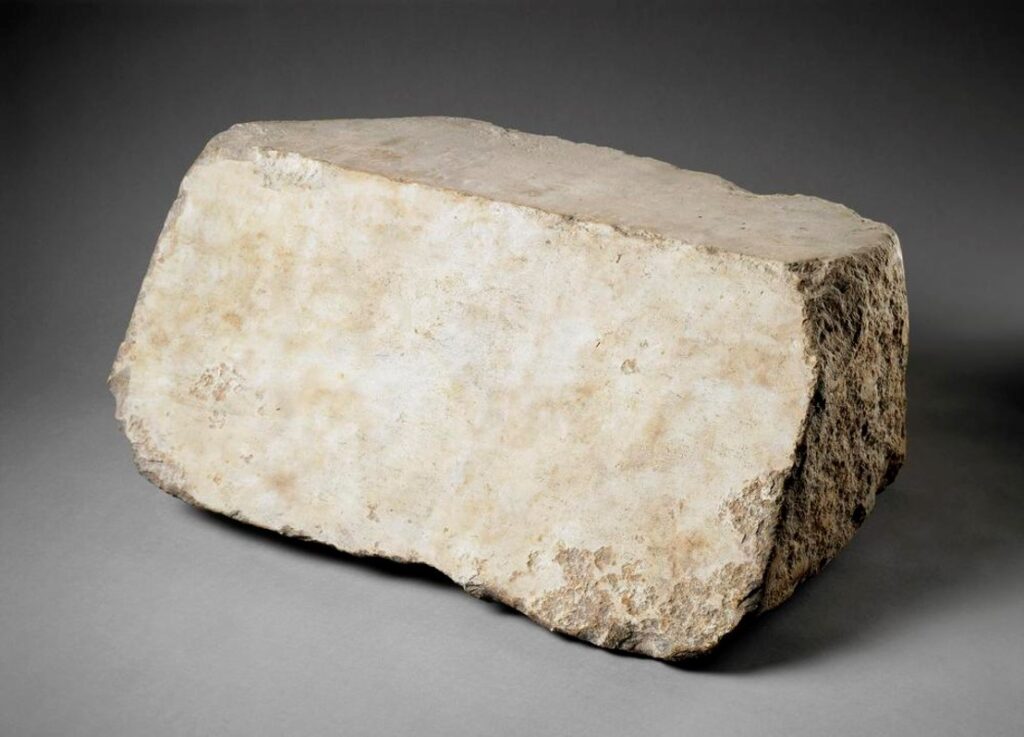

Originally the Great Pyramid was 70.2 square metres (or 440 square cubits, which is the length from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger) at its base, with a volume of 2,605,000 cubic metres. It was built primarily of roughly dressed limestone and used granite blocks for the construction of the “King’s Chamber”. When completed, the entire pyramid was covered in a smooth white limestone casing, most of which is now gone after it was removed and re-used elsewhere.

A polished limestone casing-block from the Great Pyramid weighing approximately 85 kilograms (187 pounds)

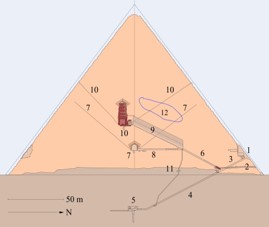

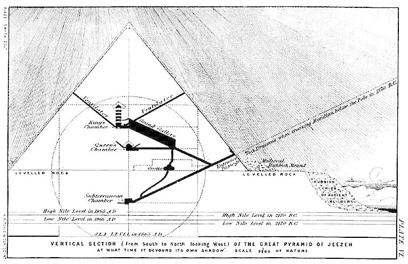

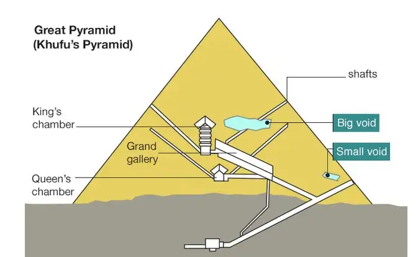

Here’s a good schematic cross-section of the Great Pyramid:

Great Pyramid of Giza schematic cross-section. 1. original entrance 2. new entrance (also call the “tourist” entrance or Robber’s Tunnel) 3. descending corridor 4. descending tunnel 5. lower chamber 6. ascending corridor 7. intermediate chamber (“Queen’s Chamber”) and shafts 8. horizontal corridor 9. Great Gallery 10. upper chamber (“King’s Chamber”) and shafts 11. vertical tunnel 12. approximate area of the “Big Void.” Image by Flanker, CC BY-SA 3.0, www.commons.wikimedia.org

Note in the diagram above that items 7 and 10 are shafts traveling up and away from the “Queen’s Chamber” and the “King’s Chamber. The shafts from the King’s Chamber currently extend completely through the pyramid to the exterior; we say “currently” because the exterior limestone cladding of the pyramid is missing so there can’t be 100% certainty. Neither of the shafts from the Queen’s Chamber extend to the exterior.

How was the approximate date for the Great Pyramid’s construction established to be around 2600 BC? Here are the technologies and methods used:

- Radiocarbon analysis of organic materials (for example wood and charcoal) found within the pyramid and its mortar;

- Thermoluminescence dating of materials such as sand and pottery;

- Comparative dating with associated structures such as temples and tombs;

- Analysis of hieroglyphic inscriptions and textural records such as those detailing the construction of the pyramid, which may not directly date the pyramid but provide information on the pharaoh responsible for the construction and the timeframe of construction;

- Dendrochronology studies of tree rings of wooden objects found at the site, including those associated with the pyramid’s construction; and

- The context of the construction in terms of design, style and materials used during a particular Egyptian cultural and architectural era.

- Clay seal from the Great Pyramid inscribed with the name of Khufu. www.collections.louvre.fr

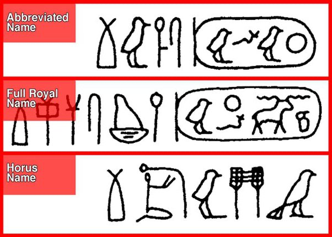

- The name Khufu expressed in different hieroglyphic forms.

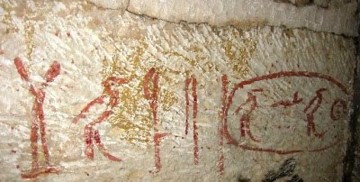

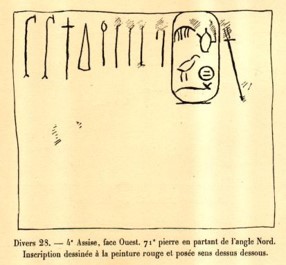

- Tag on a block found in the Great Pyramid of an Egyptian building gang named “Friends of Khufu” with hieroglyphic graffiti reading “The Gang, Friends of Khufu” Image by Robert Bauval

- Statuette in ivory of King Khufu wearing the Red Deshret Crown of Lower Egypt and the Shendyt, a royal, short pleated kilt with his name decorating both sides of throne. Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, 2589-2566 BC Found in 1903 by Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie. From the Temple of Osiris at Abydos. www.egypt-museum.com

What was the “Queen’s Chamber”?

Apparently it received this name from early Arab explorers who traditionally buried their kings in flat-roofed chambers and queens in corbeled chambers.

Today we’re no longer certain that the “Queen’s Chamber” was actually intended for a queen. It might have been intended to be sealed off to form a Serdab (a narrow chamber for the “ka” statue of the King, a place for the King’s spiritual soul). Or, it might have been originally intended to hold the sarcophagus and body of the King but this plan was later changed to the higher location of the ‘King’s Chamber”. For simplicity and consistency with convention, we’ll continue to call this the “Queen’s Chamber”.

The King’s Chamber

The shafts in the King’s Chamber have been known for many centuries, from ancient tomb robbers who broke their way into the pyramid and the shafts in search of hidden treasures to Arab explorers who broke their way through previous breaches and created more.

In 1610, in his exploration of the pyramids, the English traveller, colonist, and translator George Sandys noted two holes opposite one another on each side of the upper room in the King’s Chamber (on the north wall and south wall).

- The Pyramids of Giza and the Sphinx, 1615. A journey by George Sandys. Hellenic Library – Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation www.laskaridisfoundation.org

- Granite sarcophagus or “coffer”inside the King’s Chamber. www.sickleoftruthblog.com

- The King’s Chamber showing the sarcophagus and a shaft entrance on the wall to the right. www.en.namu.wiki

Sandys also noticed that the flame of a torch was drawn into each shaft, indicating air flow in the shafts. The shaft openings were both visible and both were about the same height from the floor of the chamber, at the top of the first course of granite wall stones.

Then in 1638 the English astronomer John Greaves visited the Great Pyramid and is credited as the first visitor toundertake actual scientific measurements. Greaves mentioned the openings of the “air-shafts” in the King’s Chamber, writing that, “This made me take notice of two inlets or spaces in the south and north sides of the chamber, just opposite to one another, that in the north was in breadth 700 of 1000 parts of English foot. In the depth of 400 of 1000 parts, evenly cut, and running in strait (sic) line six feet and farther, into the thickness of the wall; on the south is larger, and somewhat round, no so long as the former, and, by blackness within it, seems to have been a receptacle for burning lamps.”

- Entrance of northern shaft in northern wall of King’s Chamber. Vincent Brown www.commons.m.wikimedia.org

- Early photograph of the opening to the King’s Chamber southern shaft dated 1872. Morton Edgar, 1910 www.ancient-origins.net

It wasn’t until two hundred years later, in 1837 under the supervision of Colonel Howard-Vyse, that extensive excavations and explorations were conducted inside the Giza pyramids. Howard-Vyse initially thought that shafts in the King’s Chamber were conduits to “hitherto unknown chambers” in the Great Pyramid. Drawings made at that time did not show “air-shafts” leading outwards from the Queen’s Chamber, as these were covered by the walls of the chamber and were not discovered until much later.

On May 15, 1837, after the northern shaft was finally cleared of debris and rubbish with the use of boring rods and water, it was confirmed that the shafts from the King’s Chamber travel to the exterior of the pyramid.

After finding the shaft opening on the north side of the pyramid, workers discovered the opening of the southern shaft by going around the pyramid and locating it in the same relative position on the southern face. Howard-Vyse’s assistant, by the name of Mr. Hill, found a stone blocking the southern shaft and with some effort managed to remove it. “Upon the removal of this block the channel was completely open; an immediate rush of air took place, and we had the satisfaction of finding that the ventilation of the King’s Chamber was perfectly restored, and that the air within it was cool and fresh”. This is how the shafts in the Pyramid came to be known as air channels, thought to be some sort of ancient climate control system.

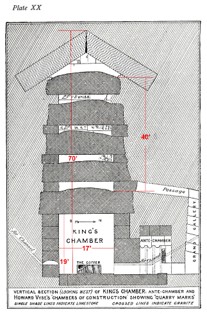

Cross-section of the King’s Chamber construction from Howard-Vyse exploration showing shafts on the right and left labelled as “Air Channel”. www.sickleoftruthblog.com

Today we know that the northern shaft is rectangular, about 12.7 centimetres high and 17.8 centimetres wide, running horizontally for about 1.8 metres, then making a series of four bends in a semi-circular path, continuing upwards at an angle of about 31 degrees for the remainder of its total 71.6 metre length.

The southern shaft is about 61 centimetres high and 45.7 centimetres wide, then narrows after a few feet to about 45.7 centimetres high and 30.4 centimetres wide, and further narrows more to about 30.4 centimetres high and 20.3 centimetres wide. Unlike the northern shaft, the southern shaft is not rectangular but has a domed top and narrow floor where it enters the King’s Chamber. It runs horizontally south for about 1.8 metres, where it bends and its shape becomes oval, continuing for 2.4 metres where it again bends slightly to the southwest to become rectangular and continue for approximately 49 metres to the outside of the pyramid. Its total length is about 53 metres, rising at an angle of about 45 degrees.

Both shafts start out horizontally through the length of granite blocks before changing to an upwards direction. The southern shaft ascends at an angle of 45 degrees, with a slight curve westwards. One ceiling stone in this shaft was found to be distinctly unfinished and was called a “Monday morning block” for this reason.

The northern shaft changes angle several times, shifting path to the west, perhaps to avoid the Big Void (more on that later). The builders seemed to have had trouble calculating the correct angles, resulting in parts of the shaft being narrower.

Today, both shafts travel to the exterior of the pyramid but because the outer casing is gone we can’t be sure if they did when the pyramid was originally completed.

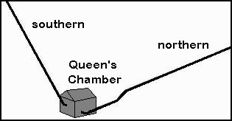

The Queen’s Chamber

The shafts in the Queen’s Chamber were originally covered by the walls of the chamber and were not discovered until 1872 in an exploration by Waynman Dixon, a British engineer. His team noted a crack in the south wall of the chamber, and behind that they discovered the rectangular opening of the shaft on the southern wall. Knowing that the King’s Chamber had two shafts, they examined the northern wall of the Queen’s Chamber and found the second shaft. Unlike the shafts in the King’s Chamber, these shafts did not draw flame or smoke into them.

Since it’s now thought that the Queen’s Chamber was actually an earlier chamber meant for the King but later abandoned, this may be why the shafts never reached the exterior of the pyramid and they were covered over by the chamber walls. (But then, if the chamber was abandoned, why bother spending the time and effort to cover them over?)

- Broken wall section in the Queen’s Chamber exposing northern shaft entrance. www.techzelle.com/great-pyramid

- Entrance to the Queen’s Chamber showing exposed southern shaft entrance on the right side. www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk

- Entrance to the Queen’s Chamber showing exposed northern shaft entrance on left side. www.en.namu.wiki

There was also an interesting find in the northern shaft. Dixon and his colleague, Dr. James Grant, found three objects in the northern shaft: a diorite/granite ball (with an indent), a double-hooked object with a shaft and two rivets, and a short “cedar-like” rod. The purpose or use of these items is unknown. The ball might have been used as a hammer with the indent being where tools or objects were struck. The hooked object might be a tool used for pulling or hooking something, or it might be a symbolic key to open the “doors” later found in the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber. The short “cedar-like” rod seems to have since disappeared.

Diorite/granite ball and double-hooked object with a shaft and two rivets discovered by Dixon and Grant in1872 and now in the British Museum. (Note that a short “cedar-like” rod was also found but has since disappeared). www.ancient-origins.net

The southern shaft of the Queen’s chamber runs horizontally for about 1.8 metres, makes an upward turn of about 38 degree, runs for about 76 metres and ends about 6 metres before the exterior of the pyramid.

The northern shaft also runs about 1.8 metres horizontally, makes an upward turn of about 38 degrees, then runs about 73 metres before again ending about 6 metres before the exterior of the pyramid.

The “Big Void”

There was another interesting discovery in 2017. A Japanese and French team using muon radiography, which is a measurement technique using cosmic rays, announced that they had detected what appears to be a large “void” above the Grand Gallery of the Great Pyramid. This void, called the “Big Void,” is thought to have a length of about 30 metres and to be similar in profile to the Grand Gallery itself. Its precise size, shape, and boundaries are yet known, nor is its purpose. It could have been used to facilitate the large block construction of the gallery and King’s Chamber, or it could be some sort of weight-relieving structure. Further, another smaller void may also have been found. The drawing below gives a general idea of where these voids are located.

Exploration of the Shafts

The southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber has been the focus of most explorations, probably because its path is the most straightforward and least convoluted with fewer bends and angles acting as unavoidable obstacles.

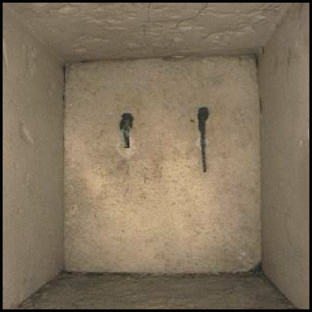

In 1993 a robot, dubbed the Upuaut-2 and designed by German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink, was sent out along the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber. At 59 meters in, it encountered a stone slab, often referred to as a “door,” blocking the way. This blocking stone appears to be highly finished, similar to the stones used in the pyramid’s casing, and has two copper fittings on its face which might be marked with seals. Both fittings appear to be flattened down and one has significantly deteriorated.

Blocking stone in the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber showing copper fittings (which appear flattened) with one significantly deteriorated. Rudolf Gantenbrink 1999

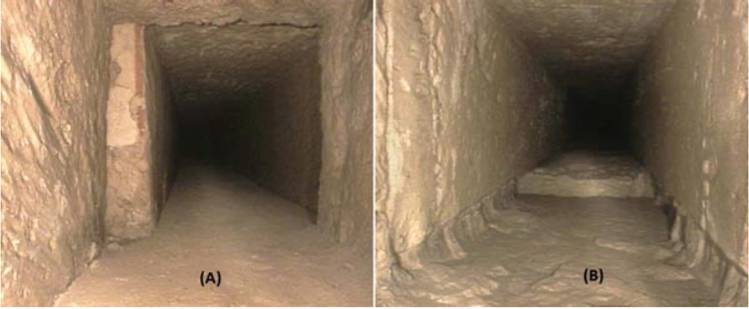

View of avoidable obstacles encountered in the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber: (A) lateral displacement. (B) floor step. Rudolf Gantenbrink 1999.

Gantenbrink also discovered a similar blocking stone in the northern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber, with similar copper fittings on its face.

A similar blocking stone in northern shaft of Queen’s Chamber also with two copper fittings. Rudolf Gantenbrink 1999

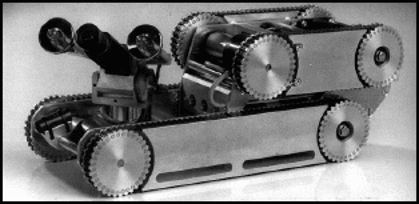

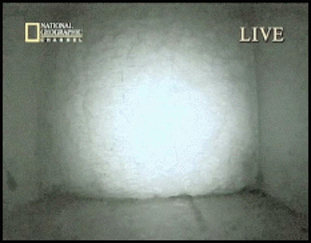

There was another exploration of the southern shaft in the Queen’s Chamber in September 2002 using the Pyramid Rover, a robot by Boston company iRobot, in collaboration with the National Geographic Society. This rover was able to insert a small fiber optic camera through a 1.9-centimeter drilled hole in the blocking slab to get a view behind it, revealing a space about 1.9 centimeters deep beyond this slab to another blocking slab.

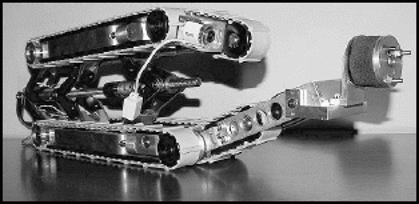

- Pyramid Rover. National Geographic Television and Film.

- Second blocking stone or slab in southern shaft Queens Chamber, about 7 inches beyond the first blocking stone or slab. Image: National Geographic Television and Film.

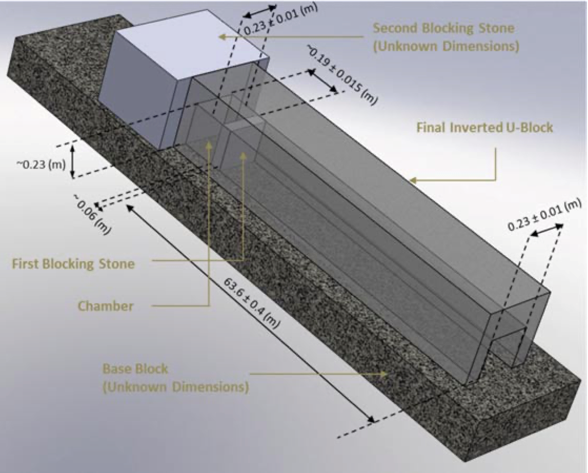

Construction of the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber showing both the first and second blocking stones. Note that the shaft consists of a u-shaped top stone sitting on a flat base stone. www.arjunnagendran.com

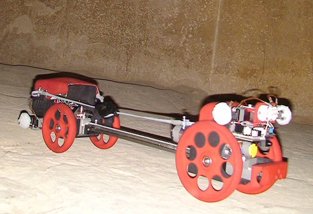

In 2011, the “Djedi Project” (named for an Egyptian magician Djedi, consulted by Khufu in the plan for the Great Pyramid) explored the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber using a new robotic design. The exploration team included leaders in the robotics industry and engineers and technicians from the University of Leeds, and was supported by Dassault Systèmes of France.

The Djedi robot included a number of innovations:

- An “inchworm-like” mobility system allowing the robot to brace its rear with telescoping sides, expand forward, brace its front and release its rear, and then contract the rear forward, repeating this as it progressed, leaving no damage to the interior of the shaft.

- A “micro snake” fiber optic pinhole camera to further examine the small chamber previously discovered.

- A small acoustic probe to measure the thickness and condition of the second blocking stone.

- A miniature “beetle” robot that could fit through a hole of 20 millimetre in diameter for further exploration in confined spaces.

- A precision compass and inclinometer to measure the orientation of the shafts.

- A core drill that could potentially penetrate the second blocking stone (through the drill hole bored by the Upuaut-2rover) while removing the minimum amount of material required.

The Djedi explorations confirmed and expanded on much of what was found on earlier expeditions as well as identifying a number of new details:

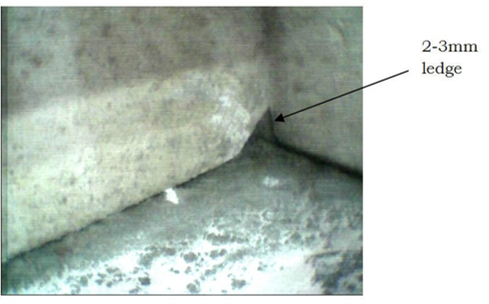

- The first blocking stone has a “chip” in the lower right hand corner as well a 2-3 millimetre ledge cut into the wall of the shaft against which the blocking stone rests.

- The copper fittings on the front of the first blocking stone appear to have been hammered down against the blocking stone and both of the ends of these fittings “pins” have been broken off either by deterioration or accidental contact in previous explorations.

- These fittings extend through the blocking stone and form loops on the back of the stone

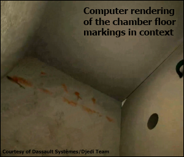

- On the floor of the space between the first and the second blocking stones there appears to be a red ochre mason’s line running parallel to the right hand wall of the space from just behind the first stone to the base of the second stone, and to the right of this line there are glyphs and markings that could be hieratic (simplified hieroglyphic) characters.

- The inside of the first blocking stone was seen to be polished, highly finished in a way that could suggest some ritualistic or symbolic purpose.

- Drilling into/through the second blocking stone was not attempted as its thickness could not be determined.

- “Chip” in the lower right hand corner of first blocking stone and a narrow ledge where the side of the stone rests. www.realrobotics.co.uk

- Composite image of markings on floor of Queen’s Chamber southern shaft between first and second blocking stones. www.realrobotics.co.uk

- Computer generated image of the front of the first blocking stone. www.realrobotics.co.uk

- Computer generated image of the back of the first blocking stone showing loops. www.realrobotics.co.uk

Planning for more Djedi explorations is underway using a modified and improved version of the robot. This will include further exploration of the Queen’s Chamber southern shaft and exploration of the chamber’s more convoluted northern shaft with the hope of resolving some mysteries:

- Since the Djedi robot was unable to determine the thickness of the second blocking stone in the southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber, this will be attempted again to determine if the second block can be drilled through to explore the other side.

- If the second blocking stone can be drilled through, to determine if there is another chamber beyond it.

- In the northern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber, to determine if there is a chamber and another blocking stone behind this first blocking stone, as well as assess its thickness and the possibility of drilling through it.

The outcomes of these objectives and others will determine what explorations might come next, as well as provide a better understanding of the limitations of current robotic technology.

So what was the purpose of the shafts?

A key point has to be mentioned up front: there is no other pyramid in Egypt known to posses similar shafts as those in the Great Pyramid. With this in mind, let’s begin by outlining some of the more innovative theories.

Energy Shafts

Some test research has been performed by blasting models of the Great Pyramid with electromagnetic waves. These tests suggest that the internal structure of the pyramid can focus and amplify microwave energy. The underlying limestone base of the pyramid could also play a role in the focusing of microwave energy, suggesting the shafts could somehow channel this focused energy. How this energy might have been used is not clear.

Hydrogen Power Plant

Using the shafts, were chemicals poured into the Queen’s Chamber to react and produce hydrogen? Could this hydrogen then be transported through the Grand Gallery into the King’s Chamber, where it could have been used to generate electricity using an electrical generator or by piezoelectric or electromagnetic methods? And were the shafts into the King’s Chamber used in somehow the same way for similar purposes?

Alien Construction

Based on the assumption that the Egyptians lacked the technology and know-how to build the pyramids, did some sort of alien life either instruct or assist the Egyptians? Or did aliens themselves build the pyramids? Did these aliens use the pyramids as some sort of navigational markers or energy sources, or for some other purpose with the shafts being somehow part of the design for the intended purpose?

Let’s look now at the more commonly proposed theories.

Light Shafts

The suggestion is that the shafts were built in order to allow light into the interior of the pyramid during construction.

- There is no other pyramid in Egypt known to posses similar shafts, so why the need for light shafts in the Great Pyramid alone?

- We know that torches or oil lamps were used for interior lighting, so why the need for these shafts to provide light?

- The shafts are not very large, so how much light would they actually have allowed in, if any?

- The angles in the shafts and the changes in direction would seem to make this use unlikely, unless there were some sort of reflective means used to carry the light around these obstacles, and no evidence of this has been found.

- Why expend the time and effort required to conceal the shafts at their entrance into the Queen’s Chamber if this were their purpose and they were no longer needed? This wasn’t done in the King’s Chamber.

This just seems like a very unlikely purpose.

Water Shafts

Here, the suggestion is that the shafts were somehow used for hydraulic lifting such that the pressure of water introduced through the shafts from above could then be used to lift large stones.

- Is there any evidence of watertight seals or sealing of any sort, to maintain hydraulic pressure?

- How would the sloped shafts each converging on a centrally located chamber be used for widespread stone lifting across the entire width and height of pyramid?

- Is there any evidence of hydraulic techniques being used? Physical indications or written records or references anywhere to the use of hydraulics in pyramid construction?

- Is there any evidence elsewhere of the Egyptians using hydraulic lifting techniques during this time period?

- Why expend the time and effort required to conceal the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber if this were the purpose and they were no longer needed. This wasn’t done in the King’s Chamber.

There doesn’t seem to be any evidence or any indications or references, at least at this point, that clearly support this theory.

Acoustic Communication

Could workers have used the shafts to talk to or shout to each other in order to co-ordinate building effort?

- How well would sound have travelled through the shafts, particularly as the pyramid became higher and wider?

- It’s not clear why workers in the chambers would need this type of communication method with workers high above or at the lateral extremities of the pyramid.

- Wouldn’t interior chamber workers have communicated with exterior workers in person by messenger or by moving in and out of the interior as required?

- Why expend the time and effort required to conceal the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber if this were the purpose and they were no longer needed? This wasn’t done in the King’s Chamber.

Again, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence or any indications or references, at least at this point, providing support for this idea. Not that it isn’t possible, but there’s no record of this idea being tested in any way and how practical or useful this would have been over the expanse of construction.

Moving Tools and Food

Could the shafts have been used to bring food or tools into the interior chambers using some sort of rope and pulley arrangement?

- How well would food containers or tools move through the shafts without being obstructed by the various turns and angles?

- Why need to use shafts for this purpose when both food and tools could have been brought in or out using the regular access routes that workers used to enter or exit the interior?

- Why expend the time and effort required to conceal the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber if this were the purpose and they were no longer needed? This wasn’t done in the King’s Chamber.

Once again, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence or any indications or references, at least at this point, providing support for this idea. Generally, the idea seems impractical and unnecessary.

Ventilation

This is probably the earliest explanation for the shafts, at least by European explorers, including the Waynman Dixon expedition in 1872, and again by the astronomer and researcher Charles Piazzi Smith in 1877. In Smith’s cross section diagram below the shafts from the King’s Chamber are clearly marked as “Ventilators.”

Plate VI from Charles Piazzi Smyth: Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid. 3rd, edition. London, 1877. www.commons.wikimedia.org

In 1692, the French consul general in Cairo and natural historian Benoît de Maillet wrote that the shafts served to provide air to workers – although he also thought that the shafts allowed those buried alive with the king to communicate with the outside – and as a means of supplying food to anyone inside.

Then during Howard-Vyse’s exploration in 1835-36, when an exterior stone blocking the southern shaft of the King’s Chamber was removed, “the channel was completely open; an immediate rush of air took place, and we had the satisfaction of finding that the ventilation of the King’s Chamber was perfectly restored, and that the air within it was cool and fresh”, which may be how the ventilation theory first came to be widely adopted.

With the later discovery of similar shafts in the Queen’s Chamber, and the fact that they were walled in and did not extend to the exterior of the pyramid, questions were raised about their possible use as ventilation shafts. But this questioning was then questioned again, with the theory that the Queen’s Chamber was not actually a chamber for a queen but was intended originally as the chamber for the king and then abandoned in favour of the higher chamber now known as the King’s Chamber. Snce the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have “doors”/blocking stones, they would have prevented exhaust/ventillation.

Is it possible the shafts were used for exhaust/ventilation?

- The unique interior plan of the Great Pyramid and the ascending passages would have caused torch and oil-lamp smoke from below to rise into the upper chambers, so a way was needed to vent this upwards and to the outside. But as work was being done up to and including the King’s Chamber, there would have been abundant exhaust ventilation above as the chamber was open overhead and was only completed as the structure rose. No other pyramids have these shafts, implying that such exhaust ventilation wasn’t needed. Or is it because of the unique interior plan of the Great Pyramid that this type of exhaust ventilation was required?

- In the many rock-cut tombs discovered, no ventilation shafts have been found. But then these rock tombs didn’t have the unique upward rising passage designs of the Great Pyramid.

- Why leave the shafts to the King’s Chamber open to the exterior of the pyramid after completion of construction? But were they actually left open to the exterior upon completion of construction? We know that the outer layer of limestone cladding was removed, and also that various explorers forced their way into the King’s Chamber exterior shaft entrances by removing exterior debris or stones. Perhaps the shafts were originally closed to the exterior after construction was finished?

- If they were used for ventilation, why are the shaft entrances in the chambers not located closer to the chamber ceilings where they would have been much better at exhaust ventilation rather than lower down in the walls closer to the floor? In some instances, the shafts begin horizontally and then change direction and angle, which would seem to significantly impede exhaust/ventilation. However, according to the Howard-Vyse exploration in 1835-36, the shafts to the King’s Chamber did provide ventilation when opened and they were also used by the Upuaut Project in 1992-93 to install an improved ventilation system.

- The shafts in the King’s Chamber are not blocked along their travel, but the shafts from the Queen’s Chamber are blocked with “doors”/blocking stones followed by a short space and then blocked again by a stone block. Maybe these “doors” were temporary devices used to prevent debris and sand from penetrating the shafts as they were being constructed upwards, and the “doors” (using their copper loops) were moved upwards as the pyramid rose. When the Queen’s Chamber was abandoned, it’s possible these doors were left in their last position and blocked in as the pyramid rose. Did the King’s Chamber once also use these type of “doors” as well for the same purpose? And wouldn’t these “doors” have been a significant impediment to ongoing exhaust/ventilation?

- Why expend the time and effort needed to cover over the shaft entrances into the Queen’s Chamber walls if the shafts were for exhaust/ventilation? The shaft entrances into the King’s Chamber weren’t covered.

But sometimes, maybe, the simplest explanation turns out to be the solution. Is there anything that conclusively rules out the shafts being used for ventilation?

Star Shafts and Spiritual “Ka” Guides

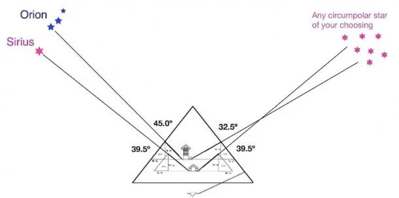

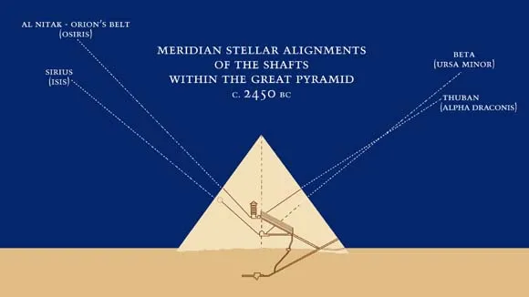

The “Star Shafts” theory seems to have been first published by academics Virginia Trimble and Alexander Badawy in the 1960’s. Not that the shafts were actual astronomical sight lines, but it’s suggested that they were aligned towards the heavens in such a way as to enable the king’s soul to travel to and join specific stars. (Keeping in mind that any claimed celestial alignment would need to correspond to celestial positions and observations made over 4,000 years ago.)

Trimble and Badawy suggested that the southern shaft of the King’s Chamber pointed towards Orion’s belt, which was associated with the prominent Egyptian god of the underworld Osiris, god of fertility, agriculture, life, death and resurrection.

Constellation of Orion.

The two brightest stars are Rigel and Betelgeuse and the “belt” stars are Alnitak. Image: Alnilam, Mintaka

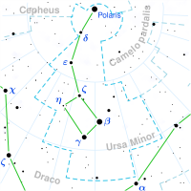

The northern shaft of the King’s Chamber points towards the star Thuban, in the constellation Draco. Although today we associate the northern star Polaris with the celestial north, in the time of the Great Pyramid the star Thuban was associated to the celestial northern pole, and with immortality, always present in the night skies.

Constellation of Draco indicating the star Thuban, in relation to Polaris (the North Star) in Ursa Minor and Ursa Major. www.skyandtelescope.org

The northern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber points toward the “Beta” star Kochab in Ursa Minor (the Little Dipper). Both Ursa Minor and the Major part of the Draco constellation were known as the hippopotamus constellation to the early Egyptians. This constellation was associated with hippo-like depictions of the goddess Taweret, goddess of pregnant mothers and newborns, of the fertility of the land and safeguarding from evil forces.

The southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber points toward the star Sirius (the “Nile Star”) which was associated with Isis, a major goddess to the Egyptians. Isis was the goddess of motherhood, protection, magic and the afterlife, ensuring the deceased safe passage in afterlife and a protective figure for pharaohs. The ancient Egyptians linked Sirius and its heliacal rising — the first day when the star is visible again in the east during the early light of dawn before sunrise – to the annual flooding of the Nile River.

Note that Orion represents the deity Osiris, and Sirius represents his consort Isis.

Also note that the circumpolar stars were viewed as undying as they circle the north celestial pole, stable and enduring, and always in nighttime view.

In 1994, in a somewhat related idea and subsequent to the publications of Trimble and Badawy, the engineer and writer Robert Bauval proposed the Orion Correlation Theory, essentially that the three main pyramids of the Giza plateau were terrestrially aligned with the three stars in Orion’s Belt as indicated in the image below: Alnitak on the Great Pyramid of Khufu, Alnilam on the pyramid of Khafre and Mintaka on the pyramid of Menkaure.

Top of this image (from bottom to top) the Pyramids of Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure. Bottom of this image (from bottom to top) the stars Alnitak, Alnilam, Mintaka of Orion’s Belt. www.en.namu.wiki

The angles of alignment between the three pyramids and the three stars of Orion’s Belt on the horizon was estimated to have existed in about 10,500 BC due to the procession of the equinoxes, significantly earlier than the widely agreed construction time of the Great Pyramid in about 2,500 BC. There are other challenges to this theory but it does speak further to ancient Egyptian knowledge of the stars and the Egyptians association of the stars with their gods and their pharaohs.

Although there are challenges to the theory that the shafts are aligned with particular stars, it could still be said that they are generally directed towards particular stars and that their intent was to guide the king’s “ka”, his essence, his soul, given at birth, persisting after death, to join his gods, towards the stars.

And yet:

- These shafts are only found in the King’s Chamber. Why not other pyramids? Why not in the pyramid of Khafre, the son of Khufu?

- And why the need for two shafts? Why point in two different star directions?

- No other type of tomb from the Old Kingdom has been found to have similar shafts.

- Egyptians believed that the spirit of the king could pass through solid rock and masonry, for example to visit his offering-temple, so why the need for a physical passage for the king to access the stars?

- Typically, a false door or representation of a door was seen as enough to guide the king’s ka to the stars, so again why the need for shafts?

- And again, why spend the time and effort to block/hide the shaft entrances in the Queen’s Chamber?

Also, in terms of the shafts being spiritual “ka” guides for the king’s ascent to the heavens, funerary texts are said to refer to a series of doors that the pharaoh’s ka would encounter on his way to the afterlife. Could this be the reason for the “doors” found in the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber? And could the copper fittings be some sort of magical keys meant to open these “doors” to allow passage to the skies? Or could they be stylized snakes meant to guard the doors?

However:

- There are no other pyramids found to have these “doors” or “snakes”.

- And why would these keys or snakes require the loops that we know are there on the back of the “doors”?

- Also, there have been no “doors” found in the shafts in the King’s Chamber.

Overall though, it does seem plausible that the shafts could have been meant to point in the direction of important astronomical features in Egyptian belief, stars that were closely associated with their gods and with the life and afterlife of their pharaohs. And/or this alignment could have been meant to guide the way or provide a path for the King’s ka to ascend to these stars.

The fact shafts for this purpose haven’t yet been found in other pyramids could be because incorporating them into pyramid construction hadn’t been considered before the time of the Great Pyramid, or because it was technically too difficult to include them in previous times, or perhaps Khufu was the first to insist on them being included. Given the complexity of including them in construction, perhaps it was decided that they were not no longer viable or no longer necessary in future construction,

In conclusion: will technology help to uncover the mysteries that remain?

On the path to resolving the mysteries, there are some facts and there are some clues. There are suggestions, implications, and inferences. There are educated guesses, innovation, and conjecture.

Based on all of what we know, or think we know, there seem to be two likely theories: either the shafts were intended as exhaust or ventilation ducts during construction of the pyramids, or the shafts were directed towards stars that were important in Egyptian beliefs either to associate the pharaoh with those stars or to guide the pharoah’s ka towards them.

But neither of these theories have been proven conclusively. We just don’t know enough, and there are currently no precedents, records, or references found that confirm the intent of the shafts.

So we’re left with the need for more exploration and the ongoing search for anything, anywhere, that might reference or suggest a clear purpose for the shafts and why they have only been found in the Pyramid of Khufu.

And So, There Is No Conclusion

It could just be that despite all the theories and informed opinions and explorations we may never be certain. But then….

“Not all mysteries are meant to be solved. Not all secrets are meant to be told.” — Liane Moriarty (author)

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Everything Has a Beginning and End, Right? Physicist Says No, With Profound Consequences for Measuring Quantum Interactions

- Cleaning the Mirror: Increasing Concerns Over Data Quality, Distortion, and Decision-Making

- Not a Straight Line: What Ancient DNA Is Teaching Us About Migration, Contact, and Being Human

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies

The opening image captioned “The Great Pyramid at Giza. Image by Photo by Ahmed Afifi on Unsplash” is an image of the Pyramid of Khafre, viewed from the northwest.

Thank you very much for pointing out the image error. The image has been replaced with one of the Great Pyramid of Khufu.