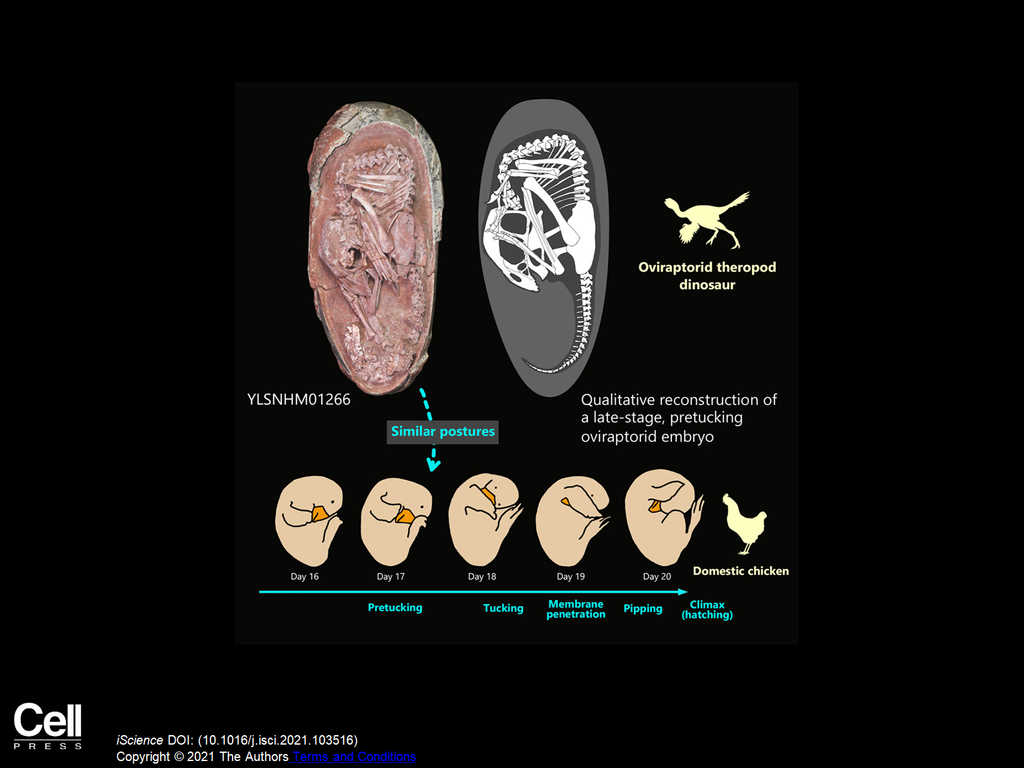

Dinosaur and chicken egg similarities. Image: Xing L. et al. (2021).

By Saulo Silvestre and Mariana Meneses

This article was updated on December 10, 2023 to report that the number of known global bird species now exceeds 11,000.

Studying extinct species like dinosaurs is especially challenging when no one has ever seen a living example.

Even so, scientists diligently assemble scant evidence of the existence of these organisms to investigate the history of life on Earth. Such evidence comes predominantly in fossils, which are extremely rare, difficult to find, and are almost always incomplete fragments of information that require a great deal of work and ingenuity to prove useful.

However, a group of researchers led by Dr. Lida Xing, at the China University of Geosciences, recently announced an exciting discovery. They published an article featuring a newly found, almost perfectly preserved, dinosaur embryo that was just about to hatch from its egg around 70 million years ago.

The egg was found in Ganzhou, southern China, and the scientists estimate it was laid sometime between 72 million and 66 million years ago.

Named Baby Yingliang, the fossilized egg belonged to a toothless theropod dinosaur, the oviraptorosaur. Oviraptorosaurs (“egg thief lizards”) are a group of feathered dinosaurs with parrot-like skulls. This group shares a common ancestry with modern-day birds and may have been primitive, flightless birds.

Oviraptosaurs ranged in size from that of a turkey to the 8-meter-long, 1.4-ton gigantoraptor. Baby Yingliang measured 27 centimeters (10.6 inches) from head to tail and was inside a 17-centimeter-long egg. It was probably a late-stage embryo about to hatch, given that it occupied most of the space within the egg. The fossil is housed at the Yingliang Stone Natural History Museum, in China.

“Theropods [are] characterized by hollow bones and three-toed limbs. [They] were ancestrally carnivorous, although several theropod groups evolved to become herbivores, omnivores, piscivores, and insectivores. Theropods first appeared during the Carnian age of the late Triassic period, 231.4 million years ago (Ma), and included all the large terrestrial carnivores from the Early Jurassic until at least the close of the Cretaceous, about 66 Ma. In the Jurassic, birds evolved from small specialized coelurosaurian theropods, and are today represented by [over] 10,500 living species.” (Wikipedia). An update indicates the number of known bird species to be now in excess of 11,000 (World Animal Foundation).

Gigantoraptor, a type of oviraptorosaur. Debivort.

Feathered dinosaurs like Baby Yingliang were commonly found in Asia and North America between 100 million and 66 million years ago – the Late Cretaceous period – and are known for their strong jaw, which they used to crack hard food like shellfish.

Their diets probably also included eggs and fish. According to Dr. Waisum Ma, one of the co-authors of the study, “[the egg] may have been buried rapidly by mud or sand, a process that protected the egg from scavengers and natural erosion.” However, since it was unearthed in 2000, the fossil remained in the museum storage and no one seemed to notice its importance – until recently.

Many oviraptorosaur egg fossils have been unearthed in recent years in Ganzhou, but none with such quality of preservation and at such a late developmental stage like Baby Yingliang.

It was only recently that the curator at the Yingliang Stone Natural History Museum noticed something special. During construction work on the museum, old fossils were being sorted and this particular egg caught the attention of experts as they suspected it could hold an embryo. This was when they noticed cracks in the fossilized egg, through which they could detect well preserved the bones.

Scientists will now use advanced scanning techniques to better study the full skeleton of the dinosaur.

This is necessary because part of the fossilized embryo is still covered by rock.

To Dr. Ma, this is “the best dinosaur embryo ever found in history.” She points out that the astounding nature of this find comes from the rarity of dinosaur embryos with almost fully developed skeletons so well preserved in their original anatomical composition. Baby Yingliang will allow scientists to move beyond a common limitation in understanding dinosaurs in their early stages, particularly while they are still inside the egg.

The discovery of Baby Yingliang sheds light on the link between dinosaurs and modern birds.

The first analyses of the embryo have already proved informative, revealing that it was in a curled position known as “tucking”, meaning that the dinosaur’s head was placed between its legs and under its body, with its back bent along the eggshell.

By tucking their heads under their wings before hatching, bird embryos have more stability and better chances of surviving the birthing process. Modern birds take this position shortly before they hatch and, until recently, scientists thought this was a unique trait. But, as demonstrated by Baby Yingliang, this behavior first evolved among their dinosaur ancestors.

Birds evolved from dinosaurs around 250 million and 66 million years ago.

Baby Yingliang reveals unprecedented similarities between a dinosaur embryo and a modern-day chick embryo.

This outstanding fossil has opened new possibilities for scientists to advance our understanding of the evolutionary past of modern birds and their ancestry. Of course, as is often the case with science, more research will still be needed. Dr. Xing’s team believes the next steps should include more precise determination of the developmental stage of the embryo and in-depth comparative studies. But already, the discovery of Baby Yingliang adds a significant brush to the picture of evolution painted by science.

The interconnectedness of the universe means that memories can sometimes be preserved in unexpected ways. For instance, while attempting to extract information about the past by imaging fossilized eggs, researchers may discover that some of that information is also present in a modern chicken egg.

Keen to explore further? Dive into our vast TQR article collection exploring captivating discussions on thought-provoking topics such as:

- Mysterious Skulls Raise Questions of Human Origins

- CRISPR Technology: Editing the Genetic Code, From Plants to Humans

- Explore Tropical Africa From Home: A Citizen Science Project

- Saving the Planet: Nobel Prize Recognizes Climate Science, but Will Mindsets Change in Time to Sustain Nature’s Potential and Value?

- Discovering the Human Code: the Most Complete Human Genome Ever Created