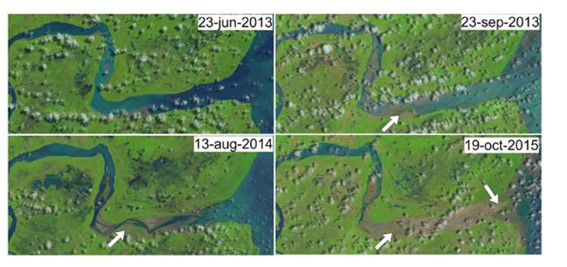

Surfing a ‘Pororoca’ (big wave in a river) is no longer possible on Brazil’s Araguari River after the river mouth filled with sand due to construction. Photo: Silva-124.

By James Myers and Mariana Meneses

This year, TQR has placed a significant emphasis on sustainability and climate change as key themes, publishing numerous articles on these topics.

Let’s take a brief look back at some of them:

In Saving the Planet: Nobel Prize Recognizes Climate Science, but Will Mindsets Change in Time to Sustain Nature’s Potential and Value?, published in May, TQR underscored the inadequacy of current climate adaptation efforts, highlighting the increasing vulnerability of human societies and emphasizing the role of sustainable land use in achieving zero carbon emissions. We discussed the significance of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics for climate research, addressing the collaboration gap in dealing with climate change, and summarized outcomes from the United Nations’ COP27 climate summit which set the stage for COP28 that began in November 2023. The conclusion stressed the ethical responsibility to transition to nature-friendly technologies for a sustainable and equitable future.

In Clean Technologies and Technologies That Clean: Undoing the Climate Damage We Have Caused, TQR discussed the lasting effect of the 2019 oil spill on Brazil’s northeastern coast, emphasizing the urgent need for remediation technologies. The article explored legislative measures, such as the European Environmental Liability Directive and the UN’s Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity. It addressed environmental challenges such as EV battery production, plastic pollution, and carbon emissions, while underscoring the significance of public awareness and responsible practices for a sustainable future.

In Preserving Biodiversity: The Race Against Ecosystem Loss, TQR underscores the critical imperative to counteract alarming extinction rates driven by human activities, such as hunting and deforestation which disrupts ecosystems, jeopardizes essential services, and poses threats to human health and agriculture. We examined solutions like rewilding and sustainable practices, while emphasizing the role of agriculture and consumer choices. The article went on to address climate change, wildlife trade, and deep-sea mining as contributors to the crisis, stressing the necessity for global cooperation, regulatory measures, public awareness, and a shift towards an Indigenous paradigm for conservation.

Reaffirming TQR’s stance that urgent action is needed to combat human-induced climate change, as evidenced by scientific findings, we continue our focus on pressing environmental issues in this December edition.

Dr. Renato Hilário

We now turn our attention to the Amazon. To discuss this vital ecosystem, TQR interviewed Amazonian biodiversity expert Dr. Renato Hilário.

Dr. Hilário is an expert in Ecology, focused on the Amazon region. He earned his Ph.D. in Zoology from the Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil, and is currently a professor at the Federal University of Amapá. Renato’s recent projects include studying the effects of replacing natural vegetation with commercial plantations, and the conservation of the Red-handed Howler Monkey, aiming to identify factors influencing their presence in forest patches within the savanna region. Through his work, Renato contributes valuable insights to the understanding of wildlife ecology and biodiversity conservation in the Amazon and beyond.

Here is the interview:

Red-handed Howler Monkey (Alouatta belzebul). Photo: Sidnei Dantas

TQR: What are you finding about the environmental threats of commercial farming and how these relate to the most pressing challenges for biodiversity in the Amazon?

Dr. Hilário: We all demand commercial goods, and so we also demand some farming to produce our food, our clothes, and these kinds of things. So, you must assume that part of the natural environment will be converted to some kind of farming. The necessary discussion should be to what we should convert the natural environment, to what kind of farming.

Large-scale farming brings income, but the income is concentrated in a few people, [while] small-scale farming distributes more equitably the income throughout the population. Also, we should think about what kind of plantations, what plants should we use in the farming. There are plants such as soybean; you have large areas of plantations with a loss of environmental services. But when you have, for example, plantations of cocoa, eucalyptus, or Amazonian fruits, together with bringing income for the population, you also maintain part of the ecosystem services. You can maintain part of the biodiversity, you can maintain carbon storage, you can maintain soil stability, and other environmental services in the area.

Photo from a 2016 operation by Brazilian authorities Ibama and the Federal Police against a criminal group responsible for illegally extracting and trading wood from the Gurupi Biological Reserve and the Caru and Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Lands, in Maranhão. Author: Ibama.

TQR: What sort of changes, maybe in the last 10 or 20 years, with respect to those factors have occurred?

Dr. Hilário: Well, the plantation type that’s spreading more rapidly in Brazil is soybean, but also corn. The regions of this expansion are changing through time. It started mostly at the southwestern part of the Amazon. And when these were more occupied, they went to Roraima and now they are coming to Amapá. (…) the Amazon is a huge area. It’s about half of the South America area, so you have some differences in these areas.

For example, the northeast area of the Amazon has more rain than the southern area and then the western area. Here in the northern area of the Amazon, you have greater forest biomass, for example [than] in the southern area. There’s also difference in the distribution of the species, especially comparing the northern margin of the Amazon River and the southern margin of the Amazon River because the river is a geographic barrier for some species. (…) And the rivers have different water characteristics; for example, there are black water rivers and the so -called white water rivers, but they have brown water, not exactly white water.

You have the lakes, and you have the flooded types of forests. You have other flooded types of vegetation, flooded fields, for example, and you have also savanna areas here at the Amazon. And most of the areas are occupied by dryland forests, that what sometimes people will think when they think about the Amazon is these dryland forests.

Most of the expansion of agriculture here in the Amazon involves large-scale farming and vast areas because land in the Amazon is cheaper than in other parts of Brazil. For instance, individuals may sell a property in southern Brazil and purchase a property in the Amazon that is 10 or even more times larger than the property they sold in the southern region of the country.

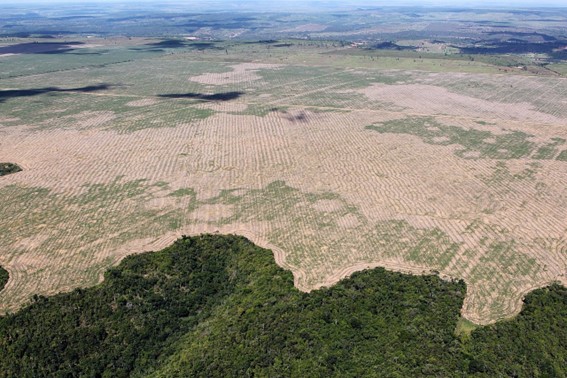

Photo: ACMMartins.

TQR: Interesting, and you mentioned the local populations, the effects of the farming activities on the local populations. Is there one effect that’s particularly concerning for you, something that when practised is specially harming some of the local communities?

Dr. Hilário: Yes, local communities rely on various resources from the environment. So, when farmers from other parts of the country come to this region, they often prevent the local people from accessing environmental goods they used to rely on, such as fishing in a lake, gathering wood from the forest, or obtaining fruits and bushmeat.

As a result, these individuals no longer have access to these essential resources. People who have access to what they need, even without using money, cannot be considered poor. However, when they lack essential resources, they become impoverished because they are not engaged in economic activities like those in urban areas. Many of the necessities are sourced directly from the environment or produced on their property, and money is only used for a small portion of their needs.

The Waiãpi and Apalai cultural groups in an official government ceremony in Amapá, Brazil. Photo: Ministério da Cultura.

TQR: Can you give us insight into how fragile some of the connections in the natural systems of the Amazon are, for those of us who haven’t been to the Amazon? I understand there’s a whole web of systems in the forest and maybe if you could give us an example of some of these connections that if they’re broken by economic activity, the kind of effects that would result and continue to cascade throughout the whole system.

Dr. Hilário: Well, it’s not new that the Amazon has vast biodiversity. The greater the biodiversity in a place, the greater the resilience of the entire system. So, there are connections between these species here. If you eventually lose any specific species, the whole system can maintain its resilience because it’s formed by many other species. The Amazonian environment is naturally more resilient than other environments. However, certain elements of this environment are more important than others naturally.

For example, you have the jaguar, a top predator. As a top predator, it controls the population of the prey species. When you lose these species from the environment, you can have a population boom of any of the prey species that remains there, for example.

TQR: And how about the soils, the water, are there any other kind of key connections in there that you think are being particularly threatened?

Dr. Hilário: There’s an example from here, the Northwestern Amazon, specifically the Araguari River, which is a significant river in this region. Initially flowing into the Atlantic Ocean, the river now features three dams for electricity generation, resulting in a reduced water flow to the ocean.

Additionally, buffalo ranching near the River Mouth has led to the buffaloes creating channels. As they dig these channels, the water flow intensifies, causing the channels to expand. The combined impact of these factors has brought about a substantial transformation at the mouth of the river, which is now dry. This alteration is also influencing other changes at the mouth of the Amazon River, contributing to erosion on the islands in that area where communities reside, necessitating their relocation due to the erosion of the islands they inhabit.

TQR: We often hear the Amazon referred to as the lungs of the earth because of the amount of carbon that the size of the forest removes from the air that we breathe. What sort of things are you seeing, in terms of how deforestation and land use changes are affecting the Amazon’s ability to protect the rest of the earth in terms of keeping the air clean and these important functions? Are there any particular examples that you’ve seen of this effect that would be concerning to a global audience?

Dr. Hilário: It’s interesting because when you see forests in other places, forests are mostly composed of smaller trees, and the same holds true here in the Amazon. However, it’s impressive to see how many large trees you can observe here, some of which have lived for centuries. When a specific forest is used for logging or clear-cutting, the first elements to perish are these magnificent trees. These large trees accumulate a significant amount of biomass, meaning they remove substantial amounts of carbon from the atmosphere.

Losing these forest areas reintroduces vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. Coupled with other human activities like burning coal and fossil fuels, this intensifies the greenhouse effect and contributes to the ongoing climate change. However, there are feedback loops in this process. For example, the current severe drought in the western part of the Amazon makes the forest more vulnerable to fires as it becomes drier. If the forest burns, more carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, creating a feedback loop that exacerbates the situation.

A mega-tree of the Amazon. Photo: Saulo Silvestre. For more on Mega-trees, see the TQR article, The Critical Role and Vulnerabilities of Nature’s Giants in Forest Ecosystems and Climate Change Mitigation.

TQR: Over the last 20 years, for example, what portion of the Amazon has been lost to cutting or burning or these other activities in terms of the actual forest?

Dr. Hilário: The current situation is that we have lost about 20% of the whole area of the Amazon since the last decades. Because at the beginning of the last century, for example, the loss of forest was minimal.

From the 70s to now, the last 50 years, for example, the deforestation increased. But this deforestation here in Brazil is concentrated in what we call deforestation arch. That is a region that goes from the easternmost part of the Amazon and to the southern part of the Amazon, forming an arch.

TQR: And are there any forecasts showing if current activities continue, what the loss will be, say, over the next decade?

Dr. Hilário: Well, there are forecasts stating that there will be a process of forest conversion into savannas because the Amazon generates its own rain. The roots of the trees draw water from the soil, releasing it into the atmosphere. This water accumulates in the atmosphere and contributes to rainfall over the forest. A portion of this rainfall extends to other regions such as Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

However, when you lose forest cover, this process is disrupted. As rainfall diminishes, the forest undergoes changes, transitioning into a different vegetation type. According to some environmental models, the vegetation will become progressively drier, and the Amazon may transform into a savanna-like area.

TQR: I understand the Amazon is home to a wealth of traditional knowledge from the people who have lived there for generations, and you’ve spoken about some of the challenges that they face with commercial activities. Are there any success stories of how these people have been brought into the question and are helping to apply their knowledge to more sustainable practices and to conserve the forest and the biodiversity there?

Dr. Hilário: Well, it’s interesting, there are many economic activities here in the Amazon that depend on the forest as a standing forest. (…) But there’s a specific example that I find impressive.

There are people from a community close to the city where I live, and this community is called Mel da Pedreira. They are descendants of African people brought to Brazil during a later period, and they form an extremely organized community. They observed a reduction in the population of a fish in the lake they used to fish, called Pirarucu. In response, they created an agreement within the community to cease fishing this species for several years. After this period, they were only allowed to fish this type of fish during a specific time of the year, with a limited amount permitted. This strategy has successfully led to the recovery of the fish population, now maintained at a sustainable level.

Additionally, this community is noteworthy for relying on the management of native bees in the forest. They have set up artificial nests for these bees, managing them to produce honey. This allows them to generate income through an economic activity while preserving the intact forest.

Wildfire in the Amazon in 2022. Image: Nilmar Lage / Greenpeace

TQR: I also understand that there has been a recent increase in wildfires in the Amazon, and we’ve actually experienced those here in Canada. How does that impact the work of conservationists in the region, those who are actively working to preserve biodiversity?

Dr. Hilário: Yeah, I think the most challenging situations are how to deal with people, especially in these areas [of] greater expansion of economic activities. Some of these people are really dangerous because they are making a significant amount of money through these kinds of activities, most of it illegally. This leads to issues like land grabbing and illegal wood exploitation, for example. Sometimes, when they learn that someone is a conservationist, for instance, they may threaten you to get you out of there and discourage interference. Consequently, your job becomes more dangerous.

“Justice for Dom and Bruno”. Image: Agência Senado.

The murders of Brazilian indigenist Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips in the Amazon in June 2022 exemplify the insecurity posed by criminals in the region, highlighting the challenges faced by environmental advocates and emphasizing the dangers inherent in protecting the area’s biodiversity.

TQR: I’ve heard also there’s a concept of ecological corridors that’s maybe being put in place or being discussed is that going to help the situation, and can you tell us a bit about what they are?

Dr. Hilário: In areas where deforestation has occurred extensively, there may be disconnected habitat patches, leading to smaller populations of animal or plant species. These smaller populations are more vulnerable to extinction due to potential genetic issues and difficulties in finding reproductive mates. Establishing ecological corridors by connecting these areas can transform three small populations into one larger, more viable population in the long run.

The challenge lies in implementing corridors, as it involves converting undeveloped land back into native areas. (…) Even during processes like land conversion for farming, the landscape can be designed to preserve and connect the remaining habitat, which is the most crucial aspect.

TQR: And is there a lot of work going into that sort of effort now, or is it just starting?

Dr. Hilário: I’m not aware of proposals for establishing corridors in the Amazon, but in other parts of Brazil, particularly in the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado, which is a savanna area, there are projects aimed at creating corridors that connect remaining habitats that are currently disconnected.

TQR: Interesting, and we spoke earlier about the global effects of changes to the Amazon. Do you ever work with any international organizations that are helping to preserve the biodiversity in the Amazon or I mean, what’s your experience been and what do you think the future for such international partnerships holds?

Dr. Hilário: I received funding for research from the Woodford Foundation, Rewild, and international organizations like conservation leadership programs. While these resources are crucial for developing research and conservation initiatives, I believe they are insufficient. The real challenge lies at the governmental or United Nations level, advocating for a shift in the economic model. I’m advocating for small-scale conservation, as the resources at my disposal limit large-scale efforts.

Economic growth often surpasses conservation capacity, especially when local governments prioritize economic activities. Achieving true conservation requires a global shift in the economic model. Changing the model globally is essential because isolated efforts may be undermined by other countries experiencing economic growth, leading their populations to aspire to similar living standards. It’s crucial to promote equity among countries and reconsider perpetual economic growth on a finite planet. By proactively addressing this issue, we can avoid potential economic collapse and implement changes without causing widespread suffering.

TQR: Are there any particular technologies that are developing that you’re seeing as potentially very helpful in the conservation efforts?

Dr. Hilário: I believe satellites are crucial because they enable remote detection of deforestation and other illegal activities, allowing us to take preventive action. Additionally, we can develop environmental models to forecast vulnerable areas, focusing our efforts on maintaining environmental integrity. This is vital as certain environmental changes can lead to cascading effects, as exemplified by the situation with the Araguari River. The damage to the river resulted in a dramatic change in the river’s mouth. Now, it is triggering another change in the mouth of the Amazon River as well.

Amazon fires 15-22 August 2019. Image: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens.

The view of the Amazon river from the International Space Station. Image: Alexander Gerst.

TQR: For somebody like me or the millions of others in the world who live thousands of kilometers away from the Amazon, who have never been there, are there any things that we can do to help even in a very small way, any habits that we can change, any economic activities that we can individually change without having a global agreement on these sorts of things?

Dr. Hilário: Well, I believe individuals can influence change through their consumption habits. Firstly, it’s crucial to reduce overall consumption, as the rising demand for natural resources places pressure not only on the Amazon but globally. Additionally, there’s a need for awareness regarding the resources required to produce the goods we purchase. We should strive for a consumption pattern that is conscious of the responsible production of the items we buy—ensuring they are made with sustainable resources and do not harm the environment or the communities, not just in the Amazon but also in other parts of the world.

TQR: If I were to ask if there was one product that I could stop consuming or consume less of that would have the most effect or the most benefit to the environment in the Amazon, what would that be?

Dr. Hilário: I think it’s meat because most of this deforestation in the Amazon is related to cattle ranching and to plantations that are aimed to produce food for animals that will become meat for people.

The Tumucumaque National Park, established in 2002, is the largest national park in Brazil and one of the largest protected areas of tropical rainforest in the world (WWF). Photo: Claudio Maretti.

TQR: So very interesting to hear. Thank you for giving us this glimpse of what it’s like in the Amazon and some of the particular issues and your own experience with it. I think it’s very important that we in the rest of the world understand this and what’s going on and what we can do about it and then also make our voices heard. Our concerns will hopefully, if we express them locally, hopefully that will have some sort of effect on the global conversation and hopefully with things like the upcoming COP28 conference, maybe there could be some real action.

Dr. Hilário: Thank you for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to talk about these things and to know that we have allies at this search to promote conservation in the world.

Dr. Hilário provided this image to TQR, explaining that it “shows what happened in the mouth of the Araguari river following the development of the channel and the construction of the dams: the mouth of the river closed and became a sandy area.” Images source.

Here is how the river used to be:

And here is how it is now:

The end of the Pororoca on the Araguari River. Photo: Jornal Nacional.

Promoting global awareness, adopting conscious consumption habits, and supporting sustainable initiatives are essential actions we can take collectively to safeguard the Amazon’s biodiversity and address environmental challenges on a global scale.

Interested in exploring related topics?

Discover these recommended TQR articles:

- Saving the Planet: Nobel Prize Recognizes Climate Science, but Will Mindsets Change in Time to Sustain Nature’s Potential and Value?

- The Future of Quantum Computing Accelerates, Many Qubits at a Time

- Revolutionizing Mobility: Are EVs, Hyperloop and Supersonic flight the future of transportation?

- Clean Technologies and Technologies That Clean: Undoing the Climate Damage We Have Caused

- Revolutionizing Food Production to Power a Growing World Population

- Preserving Biodiversity: The Race Against Ecosystem Loss