“At least three Australian raptor species intentionally spread wildfires by carrying smouldering branches to unburnt areas, according to a new paper that confirms long-held traditional Aboriginal knowledge.” (Justine E. Hausheer for Cool Green Science). Image: liesvanrompaey / Flickr.

By Mariana Meneses

Exploring Indigenous perspectives on science and technology reveals a shift towards holistic understanding of our connection with nature.

As Jim Robbins, for Yale Environment 360 reports, by collaborating with Indigenous peoples, scientists are gaining a holistic understanding of ecosystems and addressing issues ranging from climate change in the Arctic to wildfire management in Australia.

For instance, take the case of the firehawks in northern Australia, where recent research has revealed their remarkable behavior of intentionally carrying burning sticks to spread fire in order to catch prey. While this phenomenon may seem astonishing to western scientists, it has long been ingrained within the knowledge systems of indigenous communities in the region. For generations, Indigenous peoples such as the Alawa, MalakMalak, and Jawoyn have not only observed but also incorporated the understanding of fire-spreading birds into their cultural practices of landscape management.

“Attracted by the smoke, hungry kites cluster around an Australian bushfire.” Image: Dick Eussen / The Wildlife Society

Indigenous knowledge encompasses deep insights into the interconnections within ecosystems.

Indigenous communities have adapted and managed landscapes sustainably for millennia with practices like controlled burning in Australia. Moreover, through a unique perspective on the environment, this knowledge fosters mindfulness and a deep connection to nature. Despite challenges, indigenous communities maintain hope for the future, emphasizing the importance of preserving and respecting their traditional knowledge and ways of life.

To George Nicholas, in Smithsonian Magazine, the intersection between western science and indigenous traditional knowledge is highlighted by recent discoveries.

While western science historically dismissed or viewed with skepticism such traditional knowledge, its relevance to the medicinal properties of plants and to ecological management practices has been increasingly acknowledged as a valuable source of information for many scientific disciplines. However, a double standard exists in the acceptance of traditional knowledge when it is selectively acknowledged by western scientists based on alignment with their claims or challenges to scientific truths established by western scientists.

Inuit women and child in traditional parkas (also known as amauti). Image: Ansgar Walk

Arctic researcher Shari Fox emphasizes the importance of integrating traditional Inuit knowledge into Arctic research, highlighting the decades-long observation of climate change by Inuit communities.

Fox’s extensive experience working with Inuit collaborators in Clyde River informs her perspective on the co-production of knowledge and community action in the changing Arctic.

Despite their intimate relationship with the Arctic environment, most climate researchers have historically been non-Indigenous and unfamiliar with Arctic life. Fox underscores the necessity of recognizing and valuing Inuit expertise, arguing that traditional knowledge has been too often overlooked or disregarded by scientists from the south. She asserts that colonialism in science is an ongoing issue, shaping power dynamics within research.

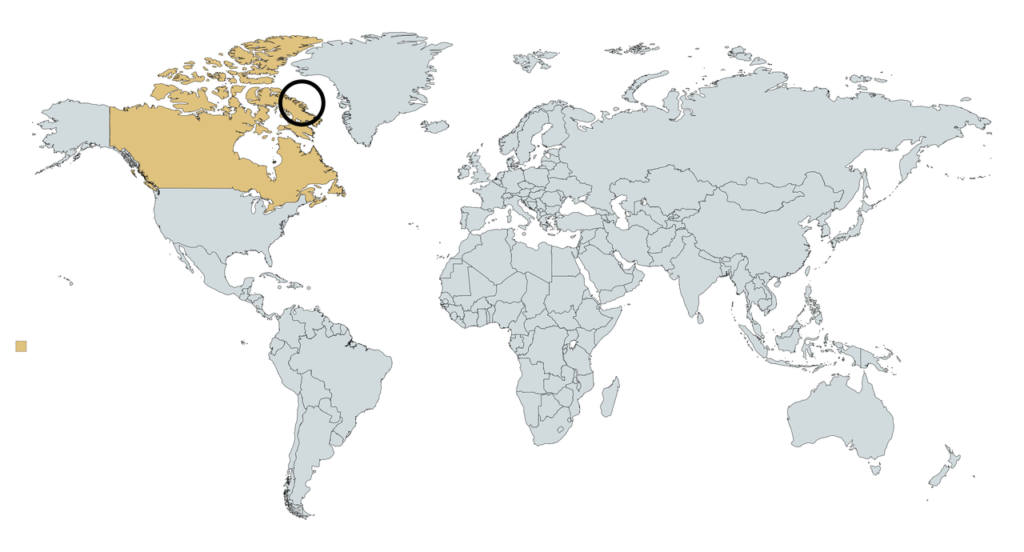

Clyde River, also known as ‘Kangiqtugaapik’ in Inuktitut, is an Inuit hamlet located on the shore of Baffin Island’s Patricia Bay, off Kangiqtugaapik, an arm of Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located approximately four degrees north of the Arctic Circle at 70° 29.4’ N, 68° 31.2’ W (ICSP Toolkit). Image: Minus40.info

Indigenous science as a time-honoured knowledge system

According to the Government of Canada, indigenous science is portrayed as a comprehensive and time-honoured knowledge system that encompasses an intricate understanding of the environment and ecosystems, cultivated by Indigenous Peoples over generations. This knowledge extends to various aspects of the natural world, including plants, weather patterns, animal behavior, and water dynamics. Canada’s Indigenous Science Division (ISD) at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), led by Anishinaabe academic Dr. Myrle Ballard, aims to integrate indigenous science with western scientific approaches to enhance decision-making processes.

Central to this endeavor are concepts like “bridging,” “braiding,” and “weaving.”

Bridging entails recognizing indigenous science as a distinct and equal counterpart to western science, fostering mutual respect and engagement. Braiding involves combining indigenous and western knowledge systems to achieve a holistic understanding of the environment while maintaining the integrity of each. Weaving encompasses all aspects of bridging and braiding, incorporating self-determined indigenous methodologies and research paradigms, aligned with international frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“SPOT: Dr. Myrle Ballard – How Science can learn from Anishinaabe mowin!” | Faculty of Science, University of Manitoba

Integration of indigenous knowledge with scientific inquiry

Sonia Verma, for Brighter World, a project of McMaster University in Canada, reports on how Gita Ljubicic, leading StraightUpNorth (SUN), collaborates closely with indigenous communities across Inuit Nunangat to address socio-ecological challenges. SUN emphasizes the integration of indigenous knowledge with scientific inquiry, recognizing the vital role of community researchers in their work.

Through qualitative and indigenous research methods, SUN documents and shares Inuit knowledge on topics such as changing weather, ice conditions, and caribou movements, aligning research priorities with community needs. Ljubicic’s team ensures that findings are shared first with community contributors before reaching broader audiences, including academic and government sectors.

In her sea ice research, Ljubicic focuses on community-driven initiatives to monitor sea ice hazards and travel routes, contributing to safety and decision-making in Nunavut. SUN facilitates research partnerships, offers training opportunities, and connects communities with funding sources, aiming to empower Indigenous voices in shaping policies and decisions that affect their homelands. Through their collaborative approach, SUN strives to bridge the gap between scientific research and community knowledge, promoting mutual respect and understanding.

“Arctic science expedition reaches North Pole due to melting sea ice”. Credit: Radio Canada International

The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) highlights the importance of integrating Indigenous Knowledge (IK) with scientific research to better understand Arctic changes.

Defining IK as a systematic way of thinking across various systems, ICC emphasizes its value in informing decision-making processes. ICC offers a definition of IK that encompasses insights from direct experiences, observations, and multigenerational knowledge, emphasizing its ongoing development and transmission. Proposed concepts include identifying research needs collaboratively, utilizing funding to gather data from both IK and scientific experts, and employing culturally appropriate methodologies.

ICC suggests a participatory approach, where IK holders and scientists work together from conception to analysis with final products peer-reviewed and validated by IK holders. Emphasizing mutual knowledge exchange in plain language, ICC advocates for recognizing and respecting the distinct contributions of both IK and scientific knowledge in Arctic research and decision-making processes.

CBC News reports on Canada’s efforts to integrate indigenous science into environmental policymaking, recognizing its importance in addressing climate change and its effects on indigenous communities. Myrle Ballard, the first director of Environment and Climate Change, Canada’s new division of Indigenous Science, aims to raise awareness of indigenous knowledge within the department and incorporate it into government policies.

Collaborative research initiatives, like studying climate change effects on polar bears with Inuit partners, demonstrate the benefits of integrating diverse knowledge systems.

Jeffrey Mervis, for Science.org, calls attention to the establishment of the Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science (CBIKS) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, funded by a $30 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). This initiative seeks to integrate Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) from indigenous communities with western science to address pressing issues like climate change, food insecurity, and the erosion of cultural heritage.

Drawing on examples like the Passamaquoddy people‘s traditional ecological understanding of coastal waters, the center aims to redefine research methodologies and data management practices. Through collaborative research hubs across the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, CBIKS will employ a “two-eyed seeing” approach, blending insights from both indigenous and western perspectives.

This initiative reflects a paradigm shift at NSF, recognizing the importance of indigenous knowledge systems in shaping research agendas and addressing global challenges. Moreover, CBIKS underscores the need for ethical considerations in data management, ensuring indigenous communities retain control over their cultural knowledge. The center’s innovative approach not only aims to advance scientific understanding but also empower indigenous scholars and communities, fostering a more inclusive and equitable research landscape.

This is of paramount importance for many reasons, one of them being the fact that large portions of many regions are composed of Indigenous peoples.

For instance, the Indigenous peoples of Peru, or Native Peruvians, are composed of many ethnic groups in present-day Peru. Their cultures developed for thousands of years before the Spanish colonization in 1532. In 2017, 5.5 million Peruvians (about 24% of the entire population) identified themselves as Indigenous peoples. Despite – or because – of their representativeness in Peruvian society, they had to fight for the incorporation of indigenous names in public records.

There are many places where the indigenous populations have been further reduced, such as in Australia, where only about 3% of the population identifies as indigenous.

Dancers at Quyllurit’i, an indigenous festival in Peru. Image: AgainErick

The emergence of globally known indigenous activists may be able to prevent the extinction of traditional knowledge by making it part of the general knowledge of modern societies.

In South America, Ailton Krenak, from the Krenak ethnic group in Brazil, is a key figure in indigenous activism, environmentalism, philosophy, poetry, and literature. His contributions have resonated globally, from the Amazon to Germany and beyond, propelling him into the forefront of discussions on indigenous rights and environmental stewardship.

Krenak’s advocacy traces back to pivotal moments in Brazilian history, notably during the debates surrounding the 1988 Brazilian Constitution when he adorned his face with traditional indigenous markings, symbolizing a potent assertion of indigenous identity in the political arena. Through his involvement in various indigenous rights organizations, such as the União dos Povos Indígenas (Union of Indigenous Peoples), the Aliança dos Povos da Floresta (Alliance of Forest-dwelling Peoples), and the Núcleo de Cultura Indígena (Nucleus of Indigenous Culture).

Krenak has consistently championed the causes of marginalized communities, reshaping the discourse on indigenous issues in Brazil and beyond.

His seminal work, “Ideas to Postpone the End of the World,” stands as a testament to his visionary outlook, sparking critical reflection and dialogue on the interconnectedness of humanity and the natural world.

“Masterclass: Ailton Krenak Ideas to Postpone the End of the World” | Programa EUROCLIMA

In “Ideas to Postpone the End of the World” Krenak explores the contemporary environmental crisis through three compelling lectures.

At its core lies a critical examination of the flawed notion of “humanity” that underpins modern society, which posits humans as inherently superior to nature, thereby justifying the exploitation of the natural world.

Krenak highlights the detrimental consequences of this belief system, emphasizing how it has contributed to the current environmental catastrophe. Moreover, he explains how our societal structures and institutions have perpetuated an alienation from nature, leading to the marginalization and even elimination of communities that resist conformity to the notion of nature’s inferiority or ‘usefulness’.

Krenak’s passionate appeal for a paradigm shift, encapsulated in the concept of “dreaming,” calls for a rejection of anthropocentrism and a reintegration of humanity within the intricate web of nature. By embracing this alternative worldview, he argues, we may uncover innovative solutions to navigate the looming crisis and forge a sustainable coexistence with the natural world.

“Ideas to Postpone the End of the World” stands not only as a poignant critique of our current trajectory but also as a beacon of hope, urging us to reconsider our relationship with the planet and envision a future where humanity lives in harmony with nature.

Ailton Krenak (left) and Davi Kopenawa (right) in the Xihopi Village, in the State of Amazonas, Brazil. Image: Christian Braga/ISA

Also from South America, Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, known as D Kopenawa, is a prominent Indigenous leader, shaman, cultural producer, and political activist from the Yanomami people in Brazil.

Kopenawa’s critique of western societies, as articulated in his seminal work “The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman,” offers a poignant indictment of the detrimental impact of western industrial civilization on both the environment and indigenous cultures. Central to Kopenawa’s critique is the condemnation of rampant materialism and overconsumption, which he perceives as driving forces behind mass violence and ecological blindness in western society.

Drawing sharp contrasts with Yanomami cultural values, Kopenawa exposes the stark realities of environmental devastation wrought by the actions of western societies, including the intrusion of missionaries and gold miners into Yanomami territory.

Through his firsthand experiences of colonization and invasion, Kopenawa provides a compelling narrative of cultural repression and loss, highlighting the tragic consequences of western expansion for Indigenous peoples. Moreover, he laments the erosion of indigenous knowledge and the marginalization of indigenous communities as significant casualties of western encroachment. Kopenawa’s critique extends to the missionary influence, wherein he recounts encounters with missionaries who sought to supplant Yanomami beliefs and culture with Christianity.

Ultimately, “The Falling Sky” serves as a powerful rebuke to the exploitative practices and disregard for indigenous wisdom that characterize western societies, urging for a reevaluation of values and a more harmonious relationship with the natural world.

“Davi Kopenawa: The Falling Sky and The Yanomami Struggle” | Brazil LAB at Princeton University

Indigenous perspectives on science and technology often emphasize a holistic understanding of the environment and its interconnectedness with culture, spirituality, and community well-being.

This perspective may involve practices such as traditional ecological knowledge, which incorporates observations and insights passed down through generations, and the use of sustainable technologies that align with indigenous values and principles. Additionally, indigenous communities may prioritize community-led research initiatives that address local needs and empower community members to participate in decision-making processes regarding the use and development of technology.

If our goal is to create a better world for future generations, can we go past our preconceptions and open our minds to traditional knowledge? Keep in mind, this could help keep us alive.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- Finding Truths: Defense and Criticism of the Scientific Method

- The Rising Power of Citizen Science: Enthusiasts Become Agents of Change

- Ecologist Urges Global Action and Sustainable Solutions to Safeguard the Amazon’s Ecosystem

- The Clock is Ticking (Faster for the Vulnerable): Climate Action and Compensation Mechanisms After COP28

- Global Challenges, Collective Solutions: A Spotlight on Citizen Science Projects

- How Many Languages Are There? Scientists Shed Light on What Animals Other Than Humans are Saying

- Breaking the Language Barrier: AI’s Multilingual Future May Change How We Understand Our Present and Past

- Collective Superintelligence: The Power of Open Source and Knowledge Sharing