Image: Gerd Altmann, on Pixabay

By Mariana Meneses

Although computational models have advanced neuroscience, a persistent challenge remains: connecting low-level physiological activity and biochemistry directly to high-level cognitive functions, and consequently to mental disorders. This difficulty stems partly from the fact that many models prioritize task performance, relying on abstract learning rules and model structures. A new study published in Nature Communications (open access), led by Anand Pathak, from the Dept. of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College, takes a different approach, using known physiological and anatomical constraints and then asking what forms of cognition emerge.

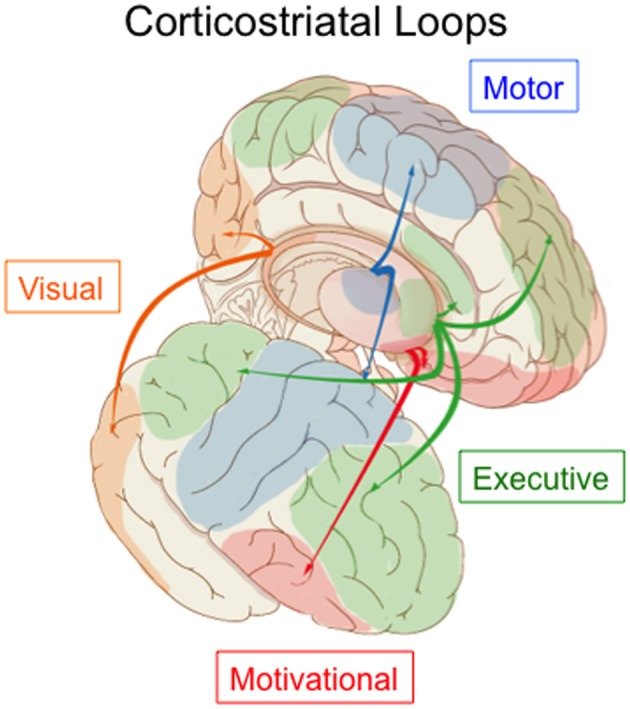

In technical terms, the study introduces a multi-scale, biomimetic computational model—in other words, a biologically inspired computer simulation—of the brain’s corticostriatal circuit. The model is designed to investigate the link between basic neural activity—which consists of neurons firing, connecting, and communicating with spiking, synapses, oscillations, and neurotransmitters—to complex cognitive abilities such as learning, memory, and decision-making.

“Corticostriatal connections play a central role in developing appropriate goal-directed behaviors, including the motivation and cognition to develop appropriate actions to obtain a specific outcome.” — Suzanne N Haber (2016)

The model is built from small, irreducible building blocks, called “biomimetic computational primitives” (BCPs), that reproduce the structure and behavior of real neural microcircuits. The article’s central claim is that cognition can emerge directly from physiological computation, with information processing that arises from how real neurons interact within known brain architectures.

Corticostriatal loops in the human brain. Image: Carol Seger (2013), in Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience.

Importantly, the new model was not tuned to experimental data. It was constructed solely from the neuroscience literature and then exposed to a standard visual categorization task previously given to macaque monkeys. When tested on this task, the simulation learned at nearly the same rate as the animals and reproduced a wide range of neural signatures (i.e., activity patterns) observed in living animals. Crucially, these physiological and behavioral similarities emerged without any training on animal data, providing strong evidence that the model captures core computational properties of the biological corticostriatal system rather than merely fitting outcomes.

One of the most significant findings was the discovery of a previously unidentified neural signal: a population of “incongruent neurons” in the simulation.

The early activity of the incongruent neurons reliably predicted upcoming errors, sometimes far in advance of the incorrect decision. Initially thought to be an artifact of the simulation, this signal was later confirmed in existing macaque data once researchers knew to look for it. These neurons appear to participate in large-scale cortico-striatal coordination and may play a role in maintaining behavioural flexibility, allowing the brain to deviate from learned rules when environmental conditions change.

Finally, the authors argue that this biomimetic approach has implications beyond explaining learning mechanisms. Because the model faithfully links neural physiology to behavior, it offers a framework for probing how specific circuit alterations (such as those associated with dopamine dysfunction, which affects motivation, learning, and decision-making) could give rise to psychiatric and neurological disorders.

By enabling controlled manipulation of neural components, the new approach opens a path for testing disease mechanisms and pharmacological interventions earlier and more systematically than is possible with animal or human studies alone, positioning physiological computation as a potential foundation for next-generation neurotherapeutics, treatments designed to prevent, manage, or repair disorders of the brain and nervous system.

Questions about how neural physiology gives rise to behavior are especially consequential in the context of mental illness, where disruptions in learning, decision-making, motivation, and cognitive flexibility are central features of many conditions. Image: Gerd Altmann, on Pixabay.

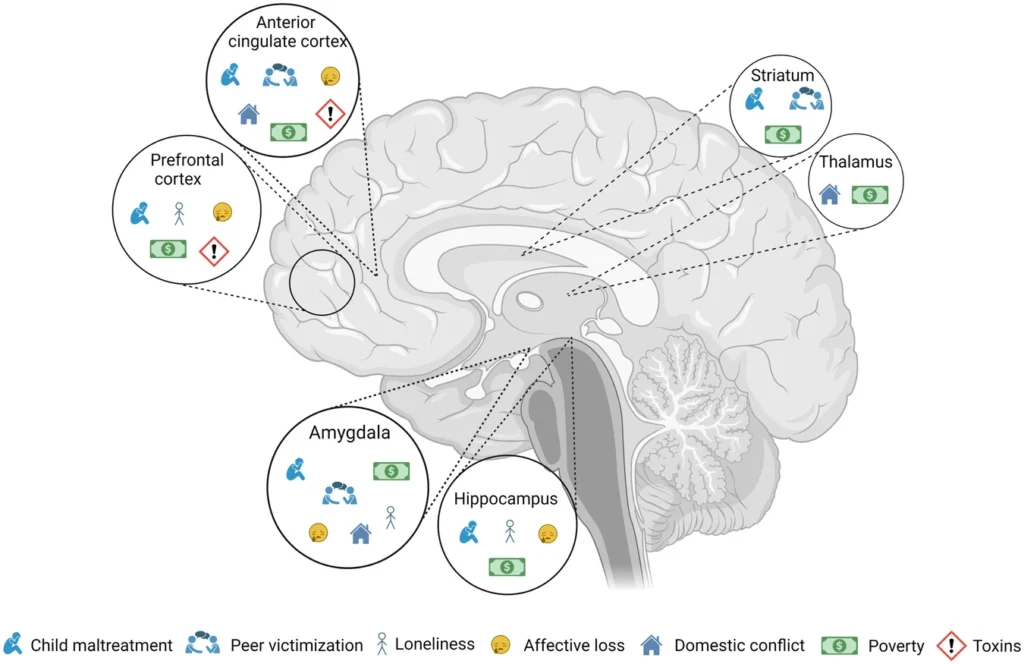

While biomimetic models dissect these disruptions at the level of neural circuits, another line of research examines how lived experiences, such as stress and trauma, can drive lasting biological changes in the same systems.

A review led by Lucinda Grummitt at the University of Sydney found consistently elevated risks of substance misuse and substance use disorders among adolescents and adults exposed to adverse childhood experiences, with effects spanning neurobiological (brain and neural circuits), endocrine (hormone regulation), immune (inflammation and defense), metabolic (energy use and body regulation), and psychosocial (behavior and social functioning) systems.

At the clinical level, a study of patients in addiction treatment in the Netherlands led by Nele Gielen from the Department of Clinical Psychological Science, Maastricht University, reports substantially higher rates of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among individuals with substance use disorders than among healthy controls, with PTSD frequently going undetected in routine clinical assessments. Together, these findings document the extent to which trauma-related processes are common, consequential, and often insufficiently recognized within addiction treatment settings.

“This schematic illustration depicts the interconnectedness between the impact of various adversities on selected brain regions. Although each adversity may have distinct manifestations, they converge on common brain regions. Understanding the cumulative effects of these adversities on the brain can provide valuable insights into allostatic load.” Source: Nilakshi Vaidya et al (2024), in “The impact of psychosocial adversity on brain and behaviour: an overview of existing knowledge and directions for future research,” published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry (open access).

If disruptions in behavior, cognition, and emotion cut across diagnostic boundaries in real-world settings, an open question is how these conditions relate to one another at the genetic level. Large-scale genetic studies have approached this problem by examining patterns of shared and disorder-specific risk across psychiatric diagnoses, offering a complementary perspective on how mental illness is structured biologically.

Published in December 2025 in the journal Nature (open access), the study “Mapping the genetic landscape across 14 psychiatric disorders”, co-authored by a large group of researchers led by Andrew D. Grotzinger, Josefin Werme, Wouter J. Peyrot and Oleksandr Frei, from the University of Colorado Boulder, discuss how psychiatric disorders are highly comorbid, which, in practice, means that many individuals meet diagnostic criteria for more than one condition over their lifetime. The authors note that this challenges the traditional view that disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, or substance-use disorders are biologically distinct.

Building on decades of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) showing widespread genetic overlap, the group set out to systematically map how shared and disorder-specific genetic risk is organized across major psychiatric conditions, using the largest and most comprehensive cross-disorder dataset assembled to date.

“A genome-wide association study (abbreviated GWAS) is a research approach used to identify genomic variants that are statistically associated with a risk for a disease or a particular trait. The method involves surveying the genomes of many people, looking for genomic variants that occur more frequently in those with a specific disease or trait compared to those without the disease or trait. Once such genomic variants are identified, they are typically used to search for nearby variants that contribute directly to the disease or trait.” — National Human Genome Research Institute.

The authors analyzed GWAS data from over one million cases spanning 14 psychiatric disorders, including neurodevelopmental, psychotic, mood, anxiety, compulsive, and substance-use conditions. The researchers combined several complementary genetic approaches to examine shared risk from different angles, such as across the whole genome, within specific regions, and in terms of underlying biological function. Together, these methods allowed them to separate genetic influences that are broadly shared across many disorders from those that are more specific to only some groups of conditions.

Genomic SEM is a model-based approach: it estimates latent factors that are hypothesized to explain patterns of genetic covariance among traits, that is, the extent to which different traits share genetic influences, and it allows the researchers to formally test how well different factor structures fit the data.

The central finding is that genetic risk across these disorders is structured around five latent genomic factors, which together explain roughly two-thirds of the genetic variance of individual diagnoses. These factors correspond to recognizable categories: compulsive disorders, schizophrenia–bipolar disorder, neurodevelopmental disorders, internalizing disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD), and substance-use disorders.

The authors also identify a higher-order “p-factor” capturing genetic risk shared across all five domains, although this general factor alone cannot fully explain cross-disorder risk. Most disorders reflect a combination of shared and unique genetic influences, rather than belonging cleanly to a single dimension.

Crucially, the researchers show that different genetic factors are enriched in different brain cell types and pathways. For example, the schizophrenia–bipolar factor is strongly associated with genes expressed in excitatory neurons. At the genome level, the authors identify both widespread pleiotropy (i.e., where genetic variants increase risk for multiple disorders) and specific genomic “hotspots” that link particular sets of conditions. This suggests that comorbidity reflects overlapping neurobiological mechanisms, not merely diagnostic imprecision.

Overall, the study provides one of the clearest genomic demonstrations that psychiatric disorders are neither fully independent nor biologically identical. Instead, they emerge from a layered genetic architecture, combining general vulnerability with more specialized pathways.

These findings have implications for how psychiatric conditions are classified, studied, and potentially treated, helping explain why symptoms and treatment responses often cross diagnostic boundaries. At the same time, the authors emphasize limitations, most notably the study’s restriction to predominantly European-ancestry data, and caution that genetic structure does not replace clinical diagnosis. Rather, it offers a complementary framework for understanding the biological foundations of mental illness.

Many fields, in many ways, have tried to understand what is in our heads. Image: freepic.diller, via Freepik.

Seen side by side, this research and the study that opened this article, from Nature Communications, tackle different parts of a shared practical challenge: how to link biological detail to mental function. The biomimetic model works from the bottom up, showing how learning and decision-making can emerge from known neural physiology when circuits are allowed to interact as they do in real brains. The genetics study approaches the problem from the population level, demonstrating that psychiatric diagnoses do not correspond to isolated biological risks, but instead reflect overlapping and structured patterns of vulnerability.

Advances like these in research have been possible due to the convergence of technologies that allow researchers to model, measure, and integrate biological detail in new ways, from physiologically grounded simulations of neural circuits to population-scale genetic analyses. Rather than replacing clinical judgment or lived experience, these tools expand the space of questions that can be asked, helping bridge the gap between molecular processes, brain dynamics, and mental function.

Want to learn more? Here are some TQR articles we think you’ll enjoy:

- Thinking in the Age of Machines: Global IQ Decline and the Rise of AI-Assisted Thinking

- Can Science Break Free from Paywalls? Technologies for Open Science Are Transforming Academic Publishing

- COP-30 in Belém: What Emerging Technologies Can and Can’t Deliver for Planetary Health

- The Science of the Paranormal: Could New Technologies Help Resolve Some of the Oldest Questions in Parapsychology?

- Digital Sovereignty: Cutting Dependence on Dominant Tech Companies

Have we made any errors? Please contact us at info@thequantumrecord.com so we can learn more and correct any unintended publication errors. Additionally, if you are an expert on this subject and would like to contribute to future content, please contact us. Our goal is to engage an ever-growing community of researchers to communicate—and reflect—on scientific and technological developments worldwide in plain language.