By Mariana Meneses

A major archaeological discovery in the Chatham Islands—an archipelago east of New Zealand—may enhance our understanding of Polynesian voyaging and canoe-building. The Guardian has recently reported on how archaeologists and local volunteers have uncovered more than 450 artefacts from a large traditional ocean-going waka (canoe), believed to be of Moriori origin.

The Moriori people emigrated from New Zealand to the Chatham Islands about 500 years ago, and the latest technology is being applied to decipher the story of how the waka was built and used. It’s one example of how modern technology is being used to decode ancient technologies and open a window on important pieces of history that had been lost to time.

The find, described as possibly the most significant of its kind in Polynesia, was first spotted by a local farmer and his son after floods exposed unusual timber in a creek. Although the exact age of the canoe is still unknown, the discovery is already being hailed for its scale, preservation, and potential to illuminate early Polynesian maritime history. Both Moriori and Māori authorities are involved in overseeing the excavation and preservation, and the local community is actively engaged in discussions about the canoe’s future.

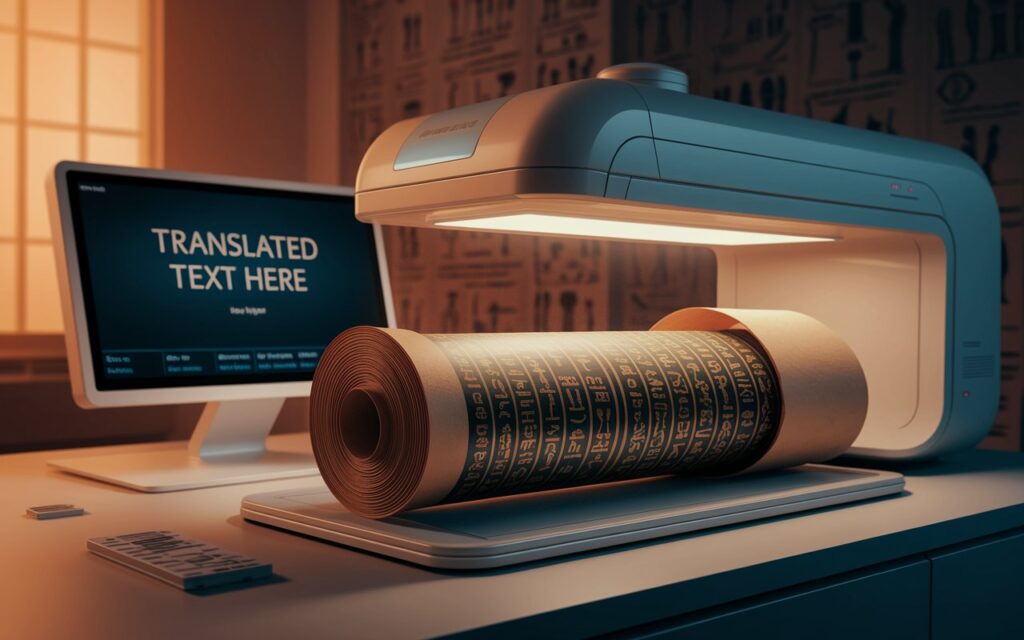

Moriori people, 1910, Chatham Islands. Image: Canterbury Museum

The New York Times reports on the revival of the Moriori, an Indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand’s Chatham Islands, long and wrongly believed to be extinct. In 1835, Moriori pacifism, rooted in Nunuku’s Law which is named after a 16-century Moriori leader, led them not to resist invading Māori tribes, resulting in mass killings, enslavement, and cultural suppression. For generations, schools promoted myths of Moriori inferiority and pre-Māori origins, discouraging identity claims. In 2021, the New Zealand government formally acknowledged these injustices through a settlement granting financial compensation, land, and cultural recognition to support ongoing revitalization.

In a 1993 New Zealand Geographic article, historian Michael King reflects on his earlier work that challenged those enduring myths. His research showed that the Moriori were Polynesians from mainland New Zealand who developed a distinct, pacifist culture on the Chatham Islands—shaped by isolation and a small population that once peaked at about 2,000 in the 18th century. Despite centuries of marginalization, King found strong continuity among descendants and a growing cultural renewal already underway.

“This waka kōrari is a replica of one type of Moriori canoe. Kōrari is the stem of the flax plant, one of the materials used in the construction of the waka, together with reeds, wood and inflated bull kelp (pōhā). Moriori designed and built new types of waka, because of the lack of large trees such as tōtara and kauri which were used for waka on mainland New Zealand.” Credit: Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Among the preserved components found recently are a remarkable range of structural and decorative elements.

These include a five-meter-long wooden plank with lash holes—likely a critical structural piece—along with intricately carved planks that retain embedded obsidian discs. Decorative elements such as iridescent pāua (abalone) shell and additional obsidian pieces were also recovered, pointing to the waka’s cultural and symbolic value. Equally significant are strings of plaited rope and fragments of woven materials, which archaeologists believe may have formed part of a sail. The variety and condition of these materials are unprecedented, offering rare insights not only into how these large canoes were built, but also into the craftsmanship and aesthetic traditions of the time.

To analyze and conserve the waka, the team is using radiocarbon dating to determine its age and material analysis to identify the origins of the wood and other components. While the article doesn’t elaborate on high-tech reconstruction tools, the research effort includes meticulous documentation and on-site conservation in water tanks to maintain the artefacts’ condition. An impromptu laboratory has been set up at the farm where the discovery was made, allowing conservators to stabilize and catalog each item. Only a small portion of the canoe has been excavated so far, with the rest reburied for protection until further decisions are made.

A waka found on the beach could be the most important discovery in New Zealand archaeology | Te Ao with Moana

Radiocarbon dating, a common method in archaeology, measures the decay of carbon-14 in organic materials to estimate their age—often accurately to within a few decades. Since the waka is made of wood, which contains carbon absorbed during the tree’s lifetime, this technique allows researchers to determine when the tree was cut down, offering clues about the canoe’s historical context. Combined with material analysis, radiocarbon dating helps place the waka within a broader timeline of Polynesian navigation and settlement, deepening both scientific and cultural understanding of the artefact.

While radiocarbon dating has been a staple in archaeological research for decades, new technologies—especially artificial intelligence—are increasingly playing a role in deepening and accelerating such investigations.

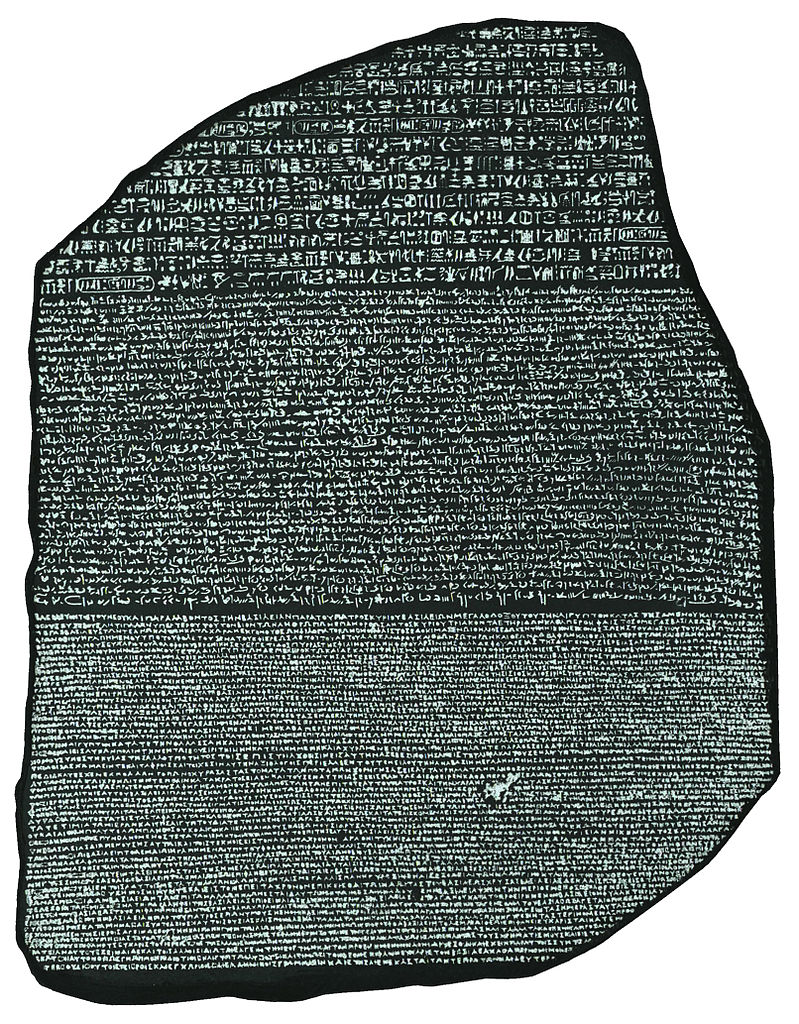

The Rosetta Stone, a granodiorite stele inscribed in three scripts—Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs—was the key to deciphering ancient Egyptian writing and unlocking the language of the pharaohs. Image: European Space Agency

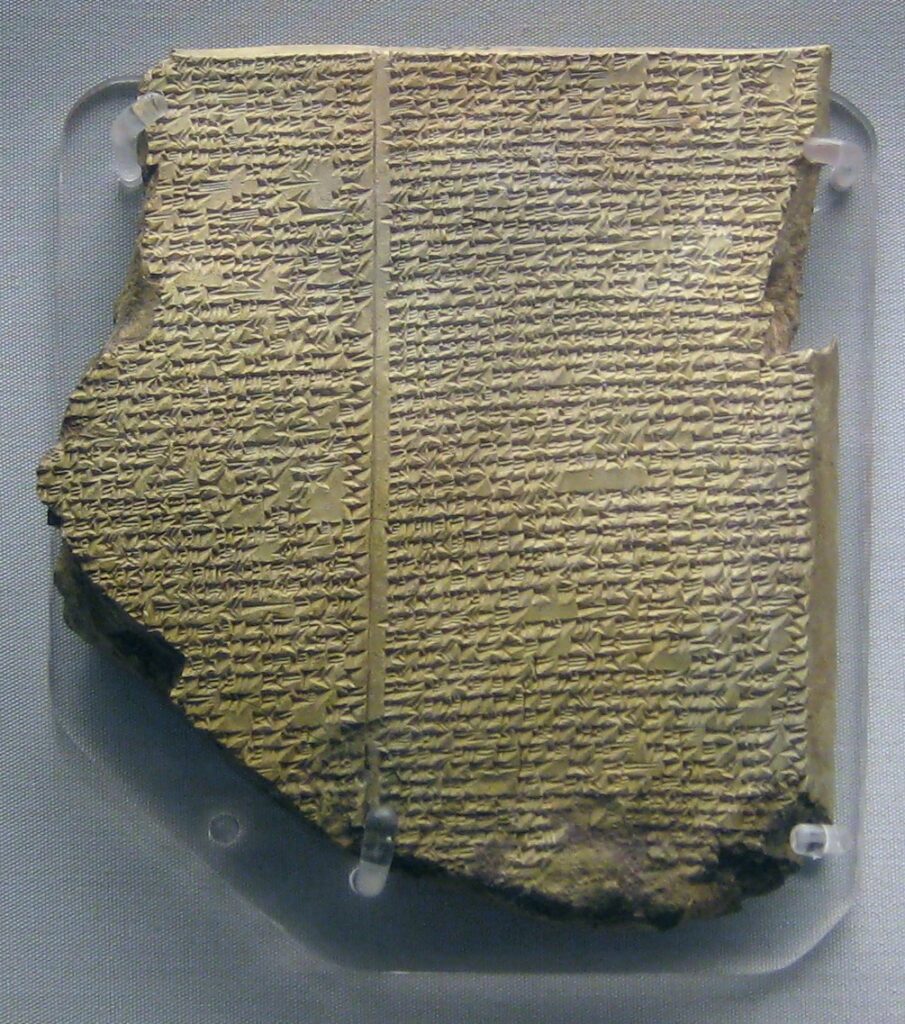

National Geographic explores how cutting-edge technologies, particularly AI, CT scanning, and genetic analysis, are transforming the way scholars engage with ancient texts once thought irretrievable due to extreme damage or illegibility. The article traces early efforts, such as the decoding of the Rosetta Stone and the Epic of Gilgamesh through meticulous linguistic comparisons, and juxtaposes them with recent breakthroughs like the virtual unwrapping of the scorched Ein Gedi Scroll, which revealed portions of the Biblical Book of Leviticus without disturbing the fragile material. It also highlights how DNA testing has advanced the reconstruction of the Dead Sea Scrolls by identifying the animal origins of parchment fragments.

A major spotlight falls on a competition called the Vesuvius Challenge, after AI models successfully extracted text from carbonized scrolls buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius—work that has already unveiled ancient reflections on pleasure and life.

A clay tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest known works of literature, written in cuneiform script in ancient Mesopotamia around 2100 BCE. The epic recounts the heroic journey of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and explores timeless themes of friendship, mortality, and the search for meaning. Image: British Museum

In 2024, The Guardian, CNN, UK Research and others reported on a historic breakthrough, as a team of young researchers—Youssef Nader (Freie University Berlin), Luke Farritor (University of Nebraska and SpaceX intern), and Julian Schilliger (ETH Zurich)—had successfully deciphered 15 columns of Greek text from a Herculaneum scroll carbonized during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. The Quantum Record previously reported on this achievement within the broader revolution in language processing powered by AI.

Using “virtual unwrapping,” a technique that combines high-resolution CT scans with advanced AI to detect carbon-based ink, the researchers revealed over 2,000 characters from a scroll believed to be authored by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus. The decoded passages reflect on the nature of pleasure and abundance, including the observation that scarcity does not necessarily increase enjoyment—a rare philosophical insight preserved for nearly two millennia.

How ancient Herculaneum papyrus scrolls were deciphered | New Scientist

This achievement earned the team the $700,000 grand prize of the Vesuvius Challenge, a global competition launched in 2023 to accelerate the reading of ancient scrolls. With over 600 scrolls still unread and the technology now proven, scholars view this as a turning point for papyrology and digital humanities, opening unprecedented possibilities for accessing the only surviving library from antiquity.

How AI Is Decoding Ancient Scrolls | Julian Schilliger and Youssef Nader | TED

In their 2025 TED Talk, Julian Schilliger and Youssef Nader recount how artificial intelligence helped unlock the ancient knowledge from 2,000-year-old carbonized papyrus scrolls. Their breakthrough involved iterative training of neural networks to recognize faint patterns as letters, eventually reconstructing over 2,000 characters and 14 columns of text without physically unwrapping the scrolls.

“We always think about the potential of AI changing the future. But what about the potential of AI changing the past?” – AI researcher Youssef Nader

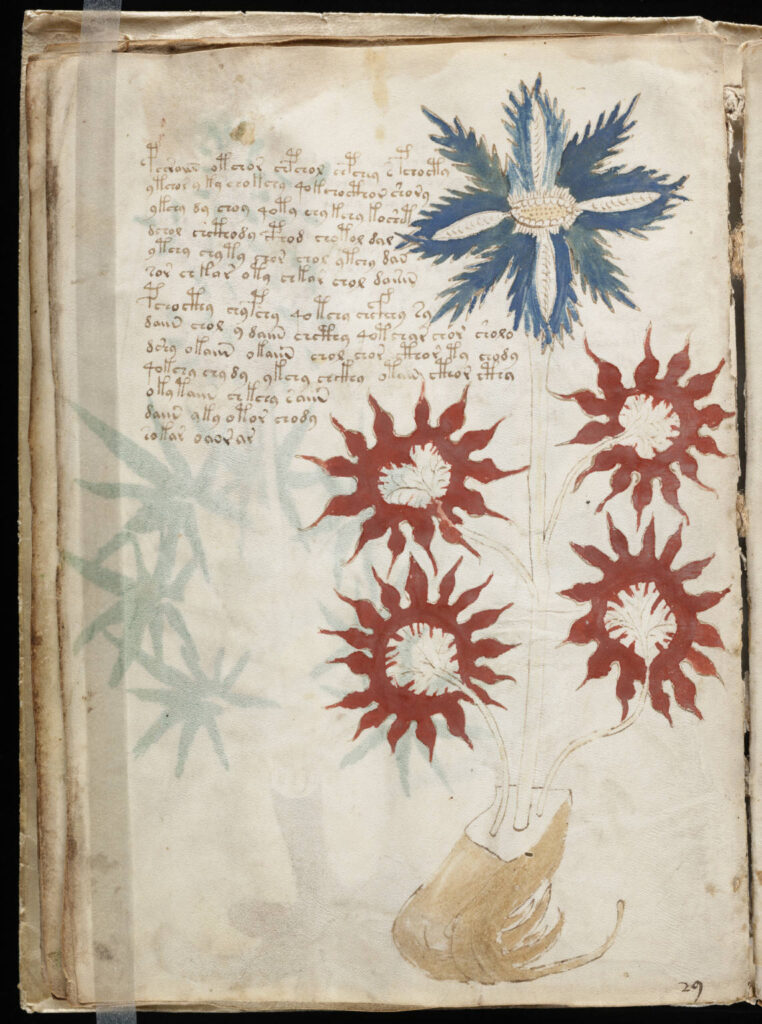

A page from the Voynich Manuscript, a 15th-century codex written in an undeciphered script and filled with mysterious botanical, astronomical, and anatomical illustrations. Its unknown language and enigmatic imagery have puzzled scholars for over a century. Image: Yale University

The National Geographic article closes with the enduring mystery of the Voynich Manuscript—carbon-dated to the early 15th century but still undeciphered despite modern advances—offering a powerful reflection on the limits of our knowledge. Even in an age of artificial intelligence and radiocarbon dating, some parts of the human story remain elusive, inviting not only answers but deeper questions about our past.

Craving more information? Check out these recommended TQR articles:

- How Many Languages Are There? Scientists Shed Light on What Animals Other Than Humans are Saying

- Wild Mathematics: Scientific Evidence of the Numerical Abilities of Animals

- Scientists Call for Halt to Creation of Mirror Bacteria, Warning of Global Risk to Life

- Time, the Sun, and Life: Even Bacteria Know When Earth Makes a Seasonal Change

- James Webb Space Telescope: Stunning Images Deliver New Insights on the Big Bang and Early Universe