Part 2: The golden age of science fiction (see Part 1) spawned a wide range of lower-budget films to ride on the popular wave and the public’s appetite for more.

By John Bamford

They were often cheesy and gimmicky, but they could also be fun entertainment, and some became cult classics. Those films became known for their following of dedicated fans, a subculture of frequent viewings and quoted dialogue, and fan participation in movie showings and fan conventions.

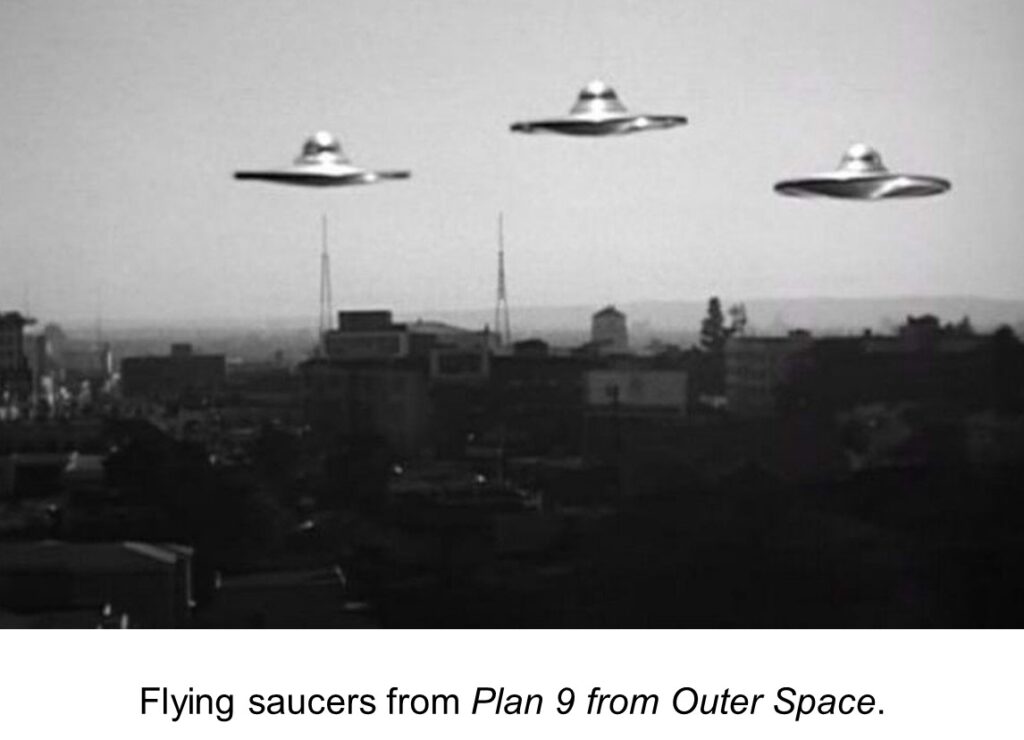

In 1957, writer, producer, and director Ed Wood released Plan 9 from Outer Space.

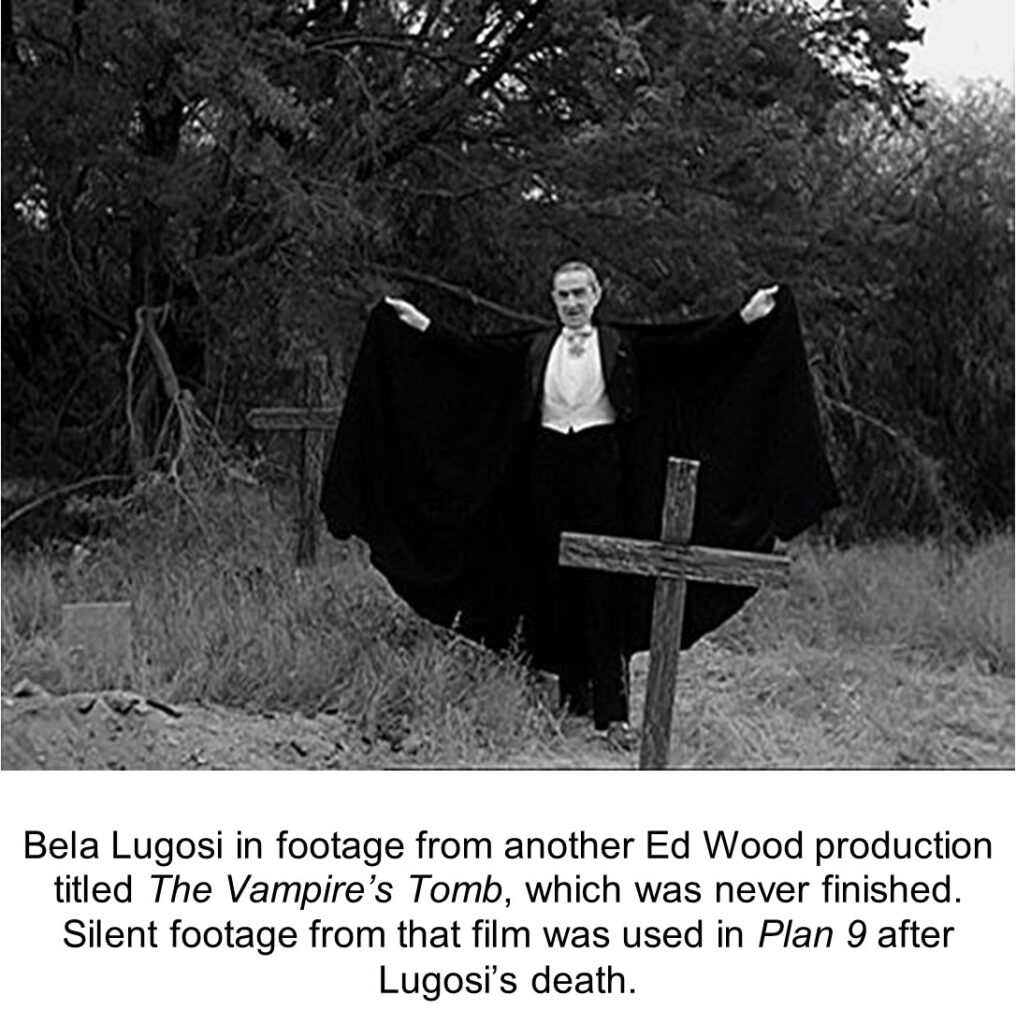

The movie starred Bela Lugosi (posthumously), “Vampira” Maila Nurmi, Gregory Walcott (frequently cast in Western movie roles), Tor Johnson (a Swedish professional wrestler and actor), and Lyle Talbot.

Originally titled Grave Robbers from Outer Space (which tells you something), it’s the story of extraterrestrials trying to stop humans from building a doomsday weapon which the aliens say will lead to the human discovery of “solarnite” that would explode sunlight molecules and threaten the universe.

The aliens land their flying saucer (naturally) at a cemetery in the Los Angeles area (naturally). After trying unsuccessfully to warn Earth governments to stop building the doomsday bomb, the aliens are left no choice but to initiate diabolical Plan 9. Spoiler alert, this involves the resurrection of recently deceased humans in a Zombie Apocalypse. But the valiant humans struggle on, and a few manage to enter the flying saucer to fight the aliens. The fight starts a fire starts inside the spacecraft, which consumes and destroys the saucer and the aliens. Earth is saved.

- Inside view of flying saucer control room, Plan 9 from Outer Space.

The film is kind of an odd combination of epic story-telling and theatre of the absurd.

Produced on a very low budget (US$60,000) and filmed in black and white to keep the cost low, it incorporated silent footage of Bela Lugosi that Wood had filmed for another Lugosi movie that was never finished before the actor’s death.

Maila Nurmi plays Vampire Girl, a female ghoul who kills two gravediggers at the cemetery where the flying saucer lands. The husband of the female ghoul is also recently deceased and buried in the same cemetery and he too is soon back wondering around with his wife and harassing the police who are called to the cemetery. It’s all a bit confusing but fun in an absurd kind of way.

The message of the film was that self-destructive human behaviour is the real threat to the Earth, not threats from outside the Earth.

It sounds a lot like the message in The Day the Earth Stood Still, and is a theme often used in sci-fi films.

Plan 9 made no profit for its investors, but it did manage to show up as a “filler” for many double-bills in theatres and drive-ins. It was eventually sold to television, often for a late- or late-late night movie, and eventually it became a cult classic. The film lived on in a 1994 film Ed Wood, depicting the making of Plan 9, which was produced on a US$18 million budget but only made US$5.9 million. That film was a critical success and went on to win two Academy Awards. All thanks to Ed Wood!

In 1952 another type of outer space sci-fi film appeared in the form of the serial.

These were multi-episode films, produced as a series of short movies shown weekly in consecutive order.

Typically, each episode ended in a cliff-hanger, keeping the audience in suspense until the next week and the next episode. They were very popular with younger viewers and often were part of an entire matinee where the audience was treated to a serial, cartoons, newsreels and usually two feature films all for the price of a single ticket.

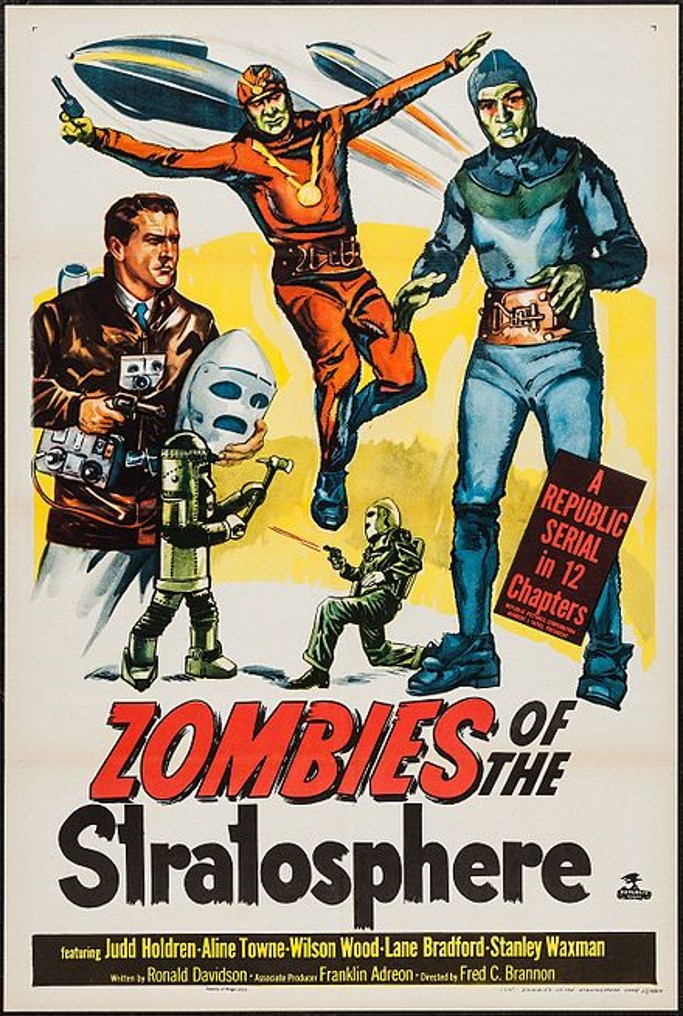

Zombies of the Stratosphere was produced by Republic Studios and, as with the stuio’s previously released serial Radar Men from the Moon/Commado Cody, it was filmed in black-and-white.

The plot of Zombies involves the lead character “Larry Martin” and his heroic comrades trying to prevent Martian invaders from displacing the Earth in its orbit so that they can move Mars to a closer position to the Sun for their planet’s survival.

To do this the Martians will use a hydrogen bomb (of course) to blow the Earth away. The evil renegade Earth scientist Dr. Harding and his crooked gang are in cahoots with the Martian Marex to steal the atomic materials they need to produce the bombs the Martians will use to destroy the Earth. Much fighting ensues between the heroes and the villains, including gunfights, fistfights, car chases, and other edge-of-your-seat stuff.

In the end, the Martian spaceship is brought down by Larry in his spacecraft during a stratospheric raygun battle. The Martians have hidden the construction site for their bomb in a secret underwater cave, but an aide to Marex named Narab (pictured here, have a look) tells Larry where the cave is located and Larry is able to defuse the bomb just in time.

Also appearing as a mechanical assistant to the Martians is the “Republic robot” described as resembling a walking hot-water heater.

Other special effects included a “rocket man” backpack and a two-way radio described as the size of a lunch box. This serial movie had it all: hydrogen bombs, jet packs, robots, Martians, alien invasion, human traitors, and Earth heroes – and all this on a budget of US$176,000 for 12 widely-viewed episodes lasting 167 minutes.

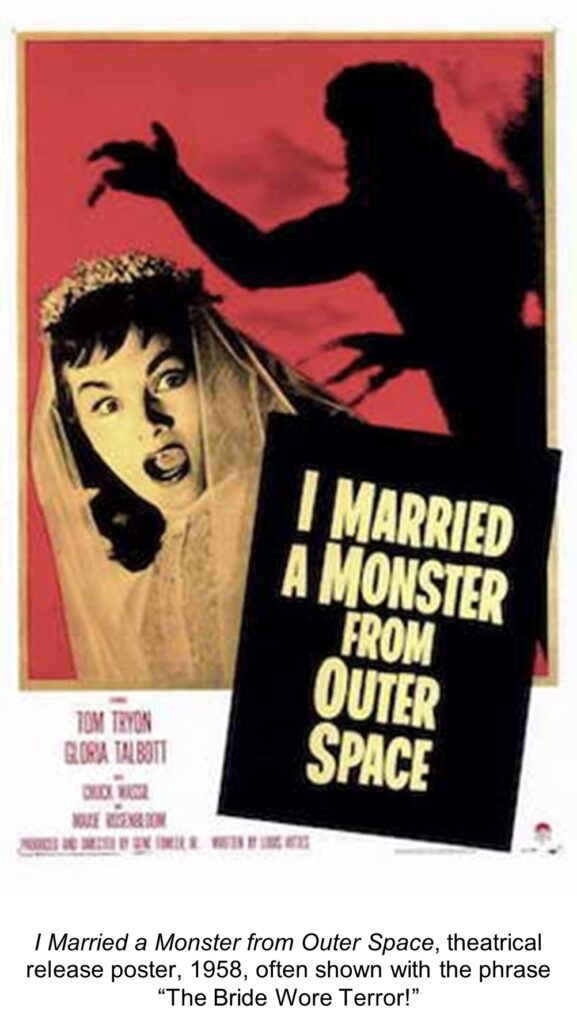

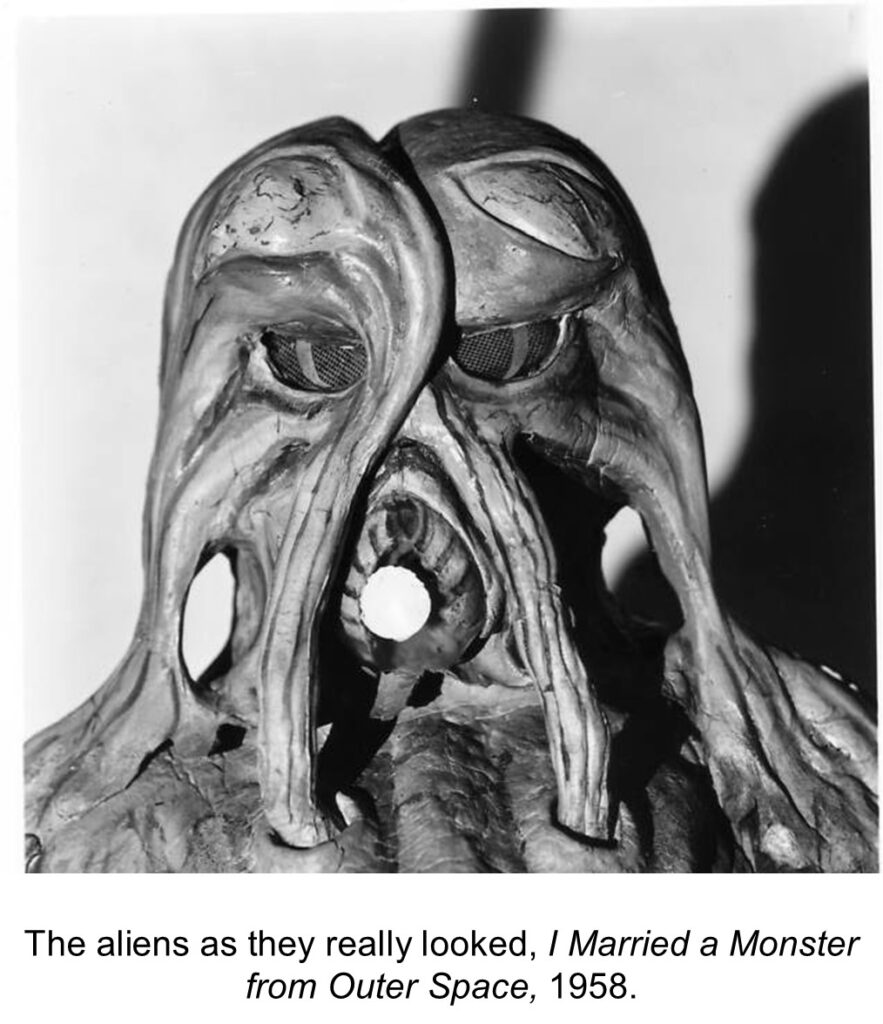

Then in 1958, a film titled I Married a Monster from Outer Space came along.

Maybe you’re thinking it was a lame outer space sci-fi comedy or spoof. In fact, this movie gem was both a critical and audience hit at the time. Sure, the title is exploitive and sensational, and that was probably the intent; it resulted in the movie being ignored by some critics and film historians.

On the other hand, audiences seemed to love it, and it was the perfect “filler” movie at drive-ins. It has been described as a story fuelled by Cold War mentality, but with sexual politics that are more interesting and disturbing.

According to one critic, although audiences are aware that in the film an alien-human coupling has occurred, the aliens fail when they cannot impregnate Earth women. Well maybe we can be thankful for that! And then from another critic, there was the suggestion of a subtext of male homosexuality because of the lead male character’s preference to meet other strange men (they were actually other aliens) in the public park rather than stay at home with his wife. Well, here’s the storyline which might help put that in context.

The male lead, Bill, leaves his bachelor party on the night before his wedding to Marge.

On the way home he is abducted by an alien who takes Bill’s shape and marries Marge. She begins noticing he’s acting strangely and eventually she concludes that he’s not the man she was engaged to. She’s particularly concerned that after a year of marriage she can’t get pregnant.

Bill leaves the house one night for a walk and Marge follows him to a park and sees him meeting with other “men” (aliens). He later explains that he is from another planet that was destroyed, and all the males were able to escape but not females. The males have come to Earth to take over the bodies of Earth men to reproduce with Earth women. Naturally, Marge is not happy with this and tries to warn everyone of the alien threat.

A lot of suspense, tension, frustration, and fear follows as Marge discovers most of the males in her town have already been replaced by aliens.

All her efforts to warn the townspeople or to escape and warn the public are frustrated, until her doctor finally believes her. He gathers together the remaining Earth men in the town, identifying them as having recently fathered children.

The alien spaceship is a hidden flying saucer (surprise!) which the Earth men posse discover.

They attempt to shoot the alien invaders, but the aliens are each surrounded by a force shield and cannot be harmed. The Earth men have a pair of German Shepherd dogs with them which the aliens are unable to stop. The aliens are killed by the dogs. Inside the spaceship the men discover all the human male captives, who are hooked up to a device that allows the aliens to assume their human form. As the human male captives are disconnected, all the aliens die. One of the dying aliens manages to warm other aliens in spaceships orbiting the Earth that they have been discovered by the humans and the spaceships all depart Earth to look for females on other planets.

I Married a Monster from Outer Space was described by critics as being intelligent, atmospheric, and subtly made, with good performances, moody camerawork and a truly exciting ending.

It’s often compared to Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Considering that it was made on a relatively low budget of US$125,000, and in black-and-white at a time when audiences were becoming more interested in full-color feature films, it was well reviewed and widely seen by audiences. It was initially released as a double feature with the full-color The Blob, which was a significant box office hit itself.

All the great outer space sci-fi themes of the decade were there: spaceships, threats of invasion, alien invasion, the secret alien takeover of human life (think Communist infiltration), and at the end the looming fear that the aliens are still out there.

The 1950s produced many more outer space sci-fi films:

- Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957);

- Robot Monster (1953);

- Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958);

- The Space Children (1958);

- Abbott and Costello Go To Mars (1953);

- Fire Maidens from Outer Space (1956).

And these are just a few!

Coming soon: Science fiction in the movies of the 1960s