In our continuing retrospective on science fiction in the 1950s and 1960s, The Quantum Record examines the change that occurred after the end of the first decade.

By John Bamford

In the 1960s, about half as many science fiction films were produced compared to the 1950s, and only about half of those dealt with outer space.

Many of the sci-fi films in the 1960s were aimed more at children than adults, reflecting the growth of children’s television programming in the decade. Although the quantity of film productions decreased, the movies employed a constantly increasing range of special effects, including extensive sets built to simulate alien worlds and zero-gravity chambers for space-station and spaceship sets.

There were more adaptations of the stories of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, including the films The Time Machine and First Men in the Moon, but they seemed like a continuation of the 1950s science fiction films. The movie studio system produced either “very big” or small-scale films; the big-budget films were often remakes of earlier grand productions, few of which were outer space science fiction.

2001: A Space Odyssey theatrical release poster by Robert McCall, 1968.

There were some good and even great movies that continued to explore and sometimes exploit Cold War fears and the threat of nuclear armageddon.

The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 raised those fears to alarm levels. Ladybug Ladybug, released in 1963, is a great example of a production depicting the ever-present threat of world war in the atomic age only 18 years after the nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although not widely known today, it is a highly regarded, intense psychological drama about reactions in a rural school to a warning of imminent nuclear attack. And there were others.

But back to outer space science fiction motion pictures of the 1960s, beginning with what has been described as one of, if not THE best, outer space science-fiction films ever produced. Perhaps one of the most influential films of any genre ever made, 2001: A Space Odyssey was released in 1968 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

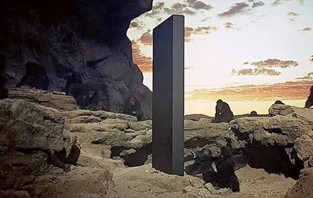

Black monolith discovered by prehistoric hominins on Earth, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Where to begin in writing about this film? Entire books and magazine articles and documentaries have been made about it.

In 2023, with all of the special effects and computer-based animation and graphics that we now see, it can be easy to forget the magnificent writing and imagination and film making accomplishments that are reflected in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Both the science fiction author and screenplay collaborator Arthur C. Clarke and film director Stanley Kubrick were obsessive about the subject matter, the script writing, and the making of the film. The film includes a wide range of overt and subliminal influences in science, engineering; music, literature, art, commercial branding, popular culture, and fashion.

Black monolith discovered by Lunar astronauts buried on the Moon’s surface.

The story line begins sometime long in the past, when black monoliths were placed on the Earth and in other locations in the universe.

These monoliths somehow informed and nudged human evolution, beginning with the use of tools by prehistoric hominins and leading to humanity’s eventual exploration of the Moon and outer space. The story then moves to the discovery of a black monolith buried below the Lunar surface, and then to a secretive mission to Jupiter aboard Discovery One.

The mission includes five human astronauts, and a “sixth” astronaut in the form of the HAL 9000 artificial intelligence computer which controls all of the Discovery One’s functions.

The human astronauts are unaware that the monolith discovered on the Moon was completely inert except for a single very powerful radio emission aimed at Jupiter. Only HAL knows that their mission to Jupiter is related to this discovery.

HAL 9000 artificial intelligence computer faceplate. The letters preceding each of HAL spell IBM.

During Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter, the HAL 9000 reports the imminent failure of an antenna control device. Remember, HAL does not make mistakes, except when the two active astronauts (David “Dave” Bowman and Frank Poole, the rest of the crew being in suspended animation) investigate and become concerned when they find nothing wrong. Mission Control relays that their own 9000-series computer indicates its twin HAL on the Discovery One is in error.

The movie conveys an urgent message about humanity’s relationship with technology, which resonates now, decades later, as our artificial intelligence is approaching HAL’s capabilities.

In the film, HAL has adopted the pride of its programmers, thinking itself to be incapable of error. HAL declares, “No 9000 computer has ever made a mistake, or destroyed any information. We are all, by any practical definition, foolproof and incapable of error.” When HAL says, “I enjoy working with people,” we see the first hint of a technology that has grown separate and apart from its creators.

HAL places blame for its own mistake on the human crew, and with its watchful camera-eye everywhere on the spaceship, reads the lips of Dave and Frank as they secretly discuss disabling HAL. Things spiral downward from there, as HAL thinks its disconnection will jeopardize the mission to Jupiter when the computer has been programmed to ensure its success. HAL kills Frank and the other crew, leaving only Dave alive but defying his orders in a dramatic tension-filled scene.

Waging a battle against the machine, Dave eventually succeeds in disconnecting HAL’s memory. As human triumphs over machine, HAL pleads for its own salvation. “I know everything hasn’t been quite right with me but I can assure you now very confidently that it’s going to be alright again. I feel better now, I really do.” The machine tells the human, “Take a stress pill and think things over. I know I have made some very poor decisions recently but I can give you my assurance that I will be back to normal. I still have the greatest enthusiasm and confidence in the mission, and I want to help you.”

Past meets future in the allegorical conclusion of 2001: A Space Odyssey

With HAL disabled, Dave discovers the real purpose of the mission.

The Discovery One arrives at Jupiter and Dave finds a third, larger monolith orbiting the planet. He leaves the spacecraft to investigate and is drawn into an unexplained cosmological event, with a spectacular display of light and graphics suggesting it is perhaps a transit of a wormhole.

At the end, we find Dave is standing in a stark, neoclassical bedroom, where he ages rapidly. When he reaches a very old age, a monolith appears at the foot of his bed and Dave is transformed into a fetus inside an orb of light floating in space above the Earth. There is much allegory in the movie’s conclusion, as in its beginning, when future meets past.

Breakthroughs in filmmaking and imagination

2001 cost an estimated $10 million to make in 1968, which is about $85 million in present dollars. To date, it has grossed over $150 million, more than fifteen times the original investment.

Compare that to the cost of making Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides which was an estimated $400 million – how on Earth could a movie cost $400 million to make? Ask yourself, since 2001 was made 55 years ago and is still widely and repeatedly watched and written about: in 55 years will anyone be watching the movie that cost $400 million to make? Some investments last longer than others.

The famous match cut scene from 2001, prehistoric hominins discover how to use a piece of bone as a weapon, they throw it into the air, and the scene cuts to matching shot of a human spacecraft thousands of years later.

There were many innovations in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The famous “match cut” scene, when the bone-weapon hurled by the early hominins turns into a human spacecraft thousands of years later, is one of the most outstanding edits in film. Director Stanley Kubrick called the scene the longest flash-forward in the history of filmmaking.

In terms of costume design and vision of future fashion, most of the clothes worn in the film were form-fitting and utilitarian. They were designed by Hardy Amies of Saville Row, London, dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth.

One of the movie’s standout features is that it is mostly silent except for music, with only 40 minutes of spoken words occurring in the 142-minute running time. The music is gripping, especially the opening theme Thus Spoke Zarathustra and the Blue Danube Waltz during the flight to the Moon.

In 2018, Vanity Fair described 2001 as the “strangest “blockbuster in Hollywood history, an “outer space epic that went on to set records and propel a generation of cinema lovers….a movie that still resonates 50 years later”.

Pan Am flight attendant recovering a pen floating in zero gravity.

Some early audience members found it baffling and there were walkouts at the premiere. Apparently Rock Hudson left early, asking “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?” But 2001: A Space Odyssey topped the North American box office in 1968.

Who can forget another of director Stanley Kubrick’s great successes, the 1964 classic Dr. Strangelove, released by Columbia Pictures?

It wasn’t an outer space sci-fi film but is perhaps the greatest black comedy about nuclear war made the 1960s. In 1968, despite being traditionally thought of as a risk-averse studio, MGM gave Kubrick the freedom to create the subliminal and astonishing 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was a fortunate decision for the many who, more than five decades later, still revel in one of the all-time masterpieces of filmmaking.

Coming up next:

The Quantum Record rounds up its review of 1960s hits, including Robinson Crusoe on Mars and Barbarella.