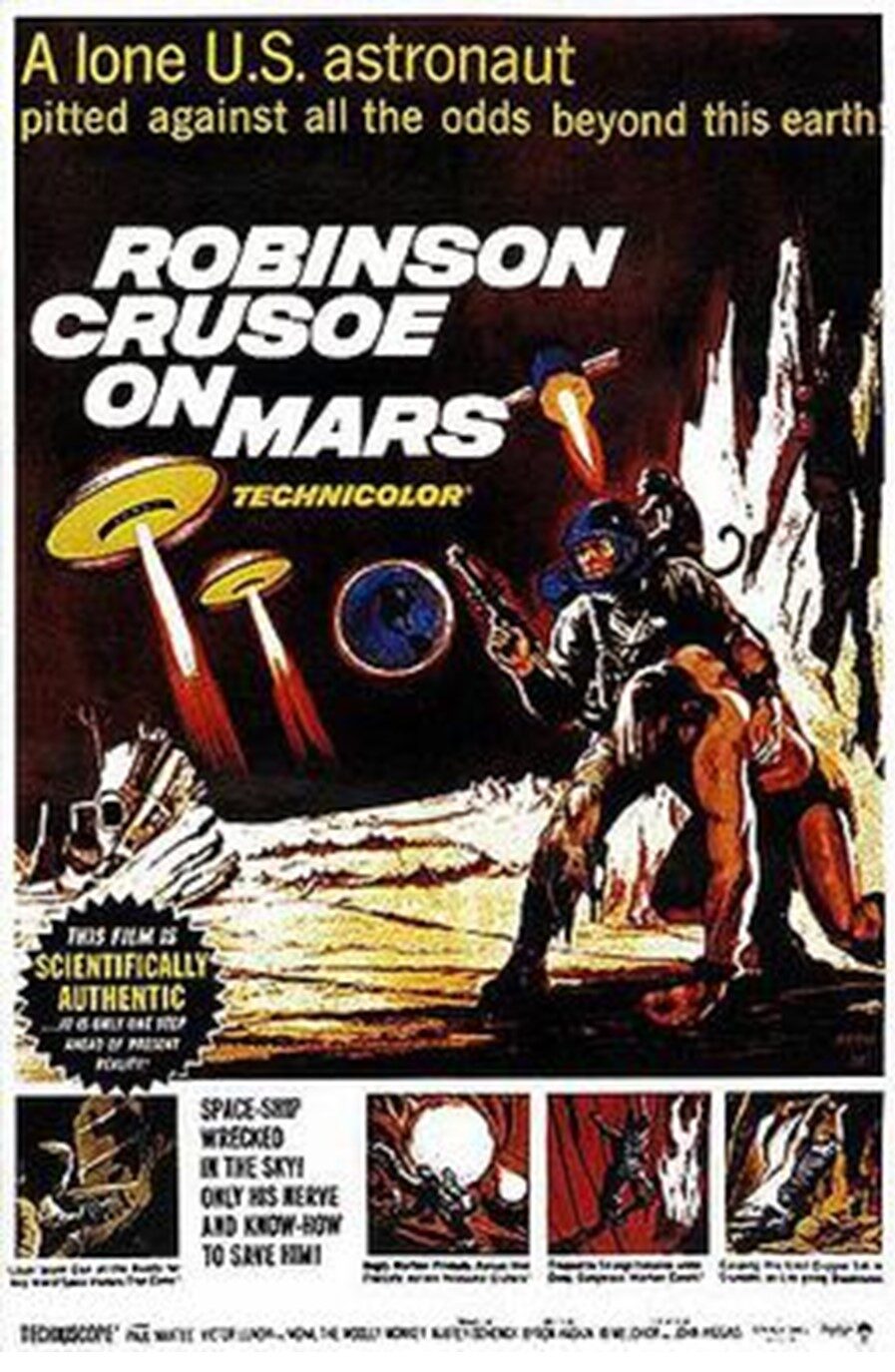

Robinson Crusoe on Mars, theatrical release poster, 1964.

As The Quantum Record explores our relationship with technology in the present, it’s worth pausing to reflect how our ancestors thought yesterday’s technology would turn out in our time. Imagine all the different paths their technology could have taken, but did not, then consider whether we are at a similar crossroads, with no sure guide to a sustainable future.

Check out the other three pieces in this series for a sense of how the past saw the present, and how our future will see its past:

- What Were They Thinking? Outer Space in Popular Imagination of the 1950s and 1960s

- What Were They Thinking? Popular Imagination of Outer Space in Motion Pictures of the 1950s and 1960s

- What Were They Thinking? The Lighter Side of 1950s Sci-fi Films and Cult Classics

- What Were They Thinking? The Past and Future of Humanity and Technology as Imagined in the 1968 Epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey

A question comes to mind in the last piece, on the masterpiece film 2001: A Space Odyssey: How similar is the HAL 9000 computer to Chat-GPT, in terms of its future potential?

Article By John Bamford

In 1964, four years before the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Paramount Pictures released Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

Although not a huge box office success, Robinson Crusoe on Mars did receive consistent critical praise. The film was directed by Byron Haskin, who also directed The War of the Worlds, released in 1953, and the 1955 film, Conquest of Space.

The film’s theatrical posters described it as “scientifically authentic,” and when it was produced, the idea that Mars had an atmosphere and water was still plausible. Shortly after the film’s release, however, discoveries were made showing that Mars had neither.

Having reached Mars in the spaceship Mars Gravity Probe 1, two astronauts, Commander Draper and Colonel McReady, and their monkey Mona, are forced to use up their fuel to avoid a large orbiting meteoroid. They escape their ship using one-man lifeboat pods to descend to Mars. McReady doesn’t survive, but both Draper and Mona do. Draper learns how to make oxygen by burning rocks, and later follows Mona to a pool of water that the monkey has discovered along with edible plants.

He discovers a dark rock slab standing almost upright (foreshadowing 2001) and a humanoid skeleton wearing a dark bracelet. It looks to him as though the humanoid had been murdered, so to hide his presence Draper signals his still orbiting spaceship to self-destruct. He sees a spaceship land in the distance, and thinking it might be a rescue mission from Earth he locates it. But what he finds are human-looking slaves to be used for mining, guarded by human-shaped aliens.

One the slaves escapes, who Draper follows and later names “Friday,” and thus the film’s relationship to the novel Robinson Crusoe, written by Daniel Defoe in 1719. Friday is also wearing a black bracelet, which is used to track and control the slaves by their alien captors. The alien ship returns and Draper, Friday and Mona manage to escape and remove Friday’s black bracelet. Eventually they see another spacecraft approaching, and determine from its radio broadcasts that it is from Earth. They are rescued by a capsule from the spaceship and depart Mars to return to Earth.

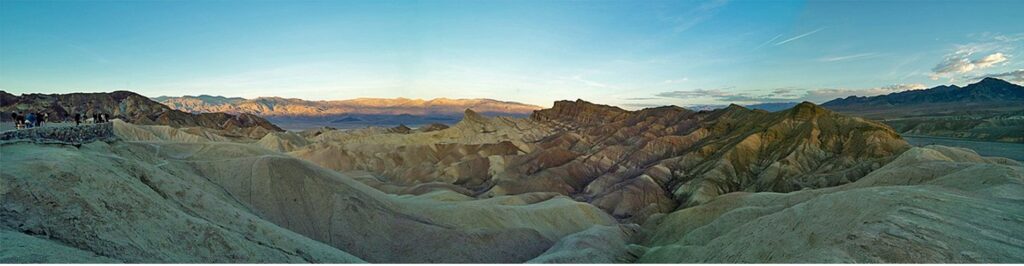

The movie was filmed mostly in Death Valley National Park at Zabriskie Point (which was also a film location for the 1950 film Spartacus), and features special effects by Lawrence Butler and matte art by Albert Whitlock (who had previously won an Academy Award for his matte art). The alien spacecraft was depicted using miniatures which were very similar to the War of the Worlds (1953) Martian war machines.

Filming location, Zabriskie Point, Death Valley Nation Park, California for Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

Robinson Crusoe on Mars became a cult classic and a favourite with dedicated sci-fi fans. And for those who collect movie memorabilia, it has provided a wealth of collectibles.

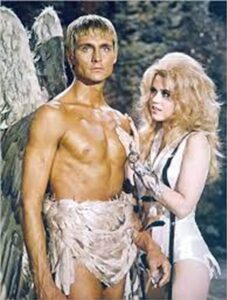

- Draper and Friday, Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

- Mona the monkey from Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

- Alien spacecraft, Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

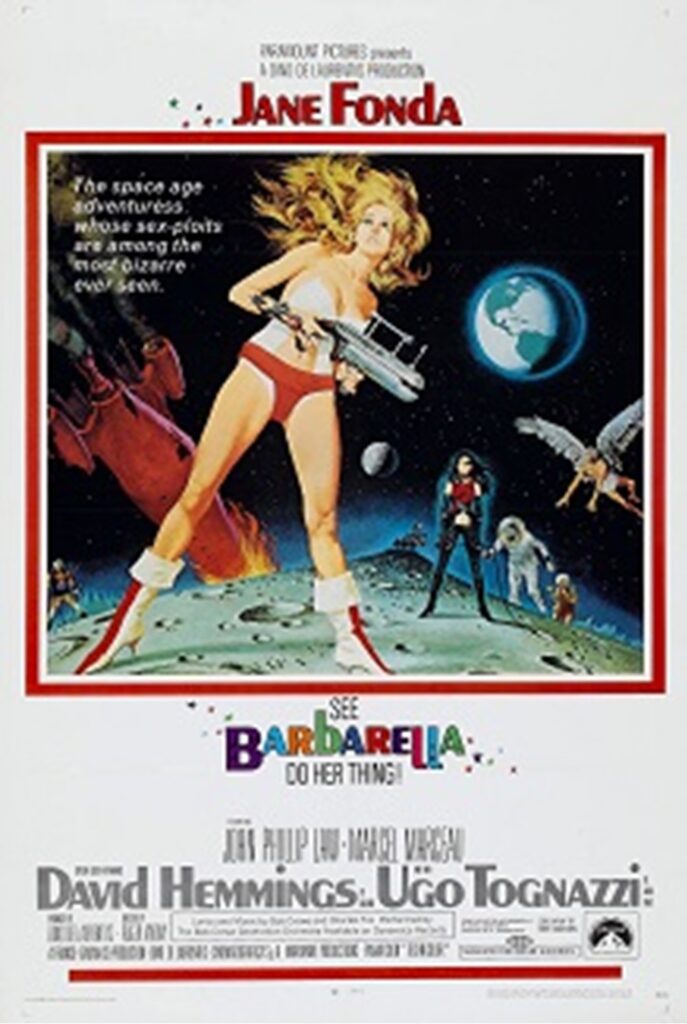

In 1968, another outer space sci-fi film was released by Paramount (in the same year as MGM released 2001). It was something quite different, in many ways.

Barbarella was produced by Dino De Laurentiis, a prolific film producer and co-producer. It was directed by Roger Vadim, who was known for visually lavish productions often with erotic qualities, which Barbarella certainly displays and which De Laurentiis described as a science fiction sex comedy. It stars Jane Fonda, who eventually married Vadim, and whom his eldest daughter described and being “the love of my father’s life.”

And yes, the film has a lot of go-go boots (derived from the French expression à gogo meaning in abundance, galore – who knew), and skimpy, tight-fitting intergalactic female attire and crazy-looking handheld space weapons. The theatrical release posters, promotional stills and photo shoots pretty much tell you what to expect.

Barbarella, theatrical release poster illustrated by Robert McGinnis.

As for the plot, Barbarella, an astronaut in the year 40,000, sets out to find and stop the evil scientist Durand Durand (yes, the band Duran Duran named itself after this character) on the planet Lythion. The evil scientist has invented the Positronic Ray weapon which in the wrong hands could threaten intergalactic war. On her journey, after she crashes her ship on Lythion, Barbarella manages to: team up with a blind angel Pygar who has lost his will to fly; encounter objects such as the Excessive Machine (a genuine sex “organ”) that Durand Durand is an expert at playing and can drive a victim to death by pleasure; and battle the evil lesbian Black Queen (The Evil Tyrant).

Pygar introduces her to Professor Ping (played by the well-known French actor and mime Marcel Marceau), who offers to repair her ship. Pygar miraculously recovers his will to fly by having sex with Barbarella. Her destination on the planet Lythion to find Durand Durand is the city Sogo, the main city of Lythion and a den of violence and debauchery. Much fantastical conflict follows. Everyone in Sogo, including Durand Durand, is killed by the creature Mathmos, which was released by the Black Queen. Pygar saves Barbarella and the Black Queen, and flies them to safety.

Jane Fonda in Barbarella.

The film seems less concerned with creating a coherent storyline than finding creative ways of undressing Fonda from her already barely-there intergalactic outfits. Is it exploitive? Is the film just about making money? Is it trash? Did it work?

It doesn’t appear to have been a huge box office success, with an estimated budget of US$4-9 million and modest box office. Described as a box office and critical failure on its release in the US, it appears to have had greater success in the UK. And, maybe you guessed this, it’s became a camp cult classic.

While some critics praised the film’s design and cinematography, others were not so generous. It was described as a nasty kind of film, modish to the core and essentially just a shrewd piece of exploitation. Another review described it as pure sub-adolescent junk and bereft of redeeming social or artistic importance. And another commented that, in the year that Stanley Kubrick and Franklin Schaffner finally elevated the science-fiction movie beyond the abyss of the kiddie show, Roger Vadim has knocked it right back down.

- Durand Durand, played by Milo O’Shea, evil genius and expert player on the Excessive Machine.

- Professor Ping played by Marcel Marceau.

- The angel Pygar played by John Phillip Law.

- The Great Tyrant, the Black Queen played by Anita Pallenberg (look up her biography).

There were many other film productions in the 1960s, some very good and some not so much.

Here are few: Marooned 1969; Planet of the Vampires (people loved vampires) 1965; Journey to the Far Side of the Sun 1969; Countdown 1968; Santa Claus Conquers the Martians 1964 (there has to be Santa Claus); Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women 1968 (yay! women); The X from Outer Space 1967 (a Japanese production); Nude on the Moon 1961 (nude!); They Came from Beyond Space 1967; Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster 1965 (Frankenstein finally got into the game); and Pinocchio in Outer Space 1965 (no it wasn’t by Disney).

In the 1960s and 1970s people were watching more and more television. And that’s where we’re heading next.

But before we leave the motion pictures of the 1950s and 1960s, let’s close with these last lines, now part of movie lore, from The War of the Worlds 1953, solemnly spoken by the narrator Cedric Hardwicke:

The War of the Worlds 1953, George Pal, Producer (left), with Cedric Hardwicke, who narrated the film.

“The end came swiftly [for the Martians]. All over the world, their machines began to stop and fall. After all that men could do had failed, the Martians were destroyed and humanity was saved by the littlest things which God, in His wisdom, had put upon this Earth.”

Suction-tipped fingers of a Martian, dying from a common cold. The War of the Worlds 1953.

A great movie!